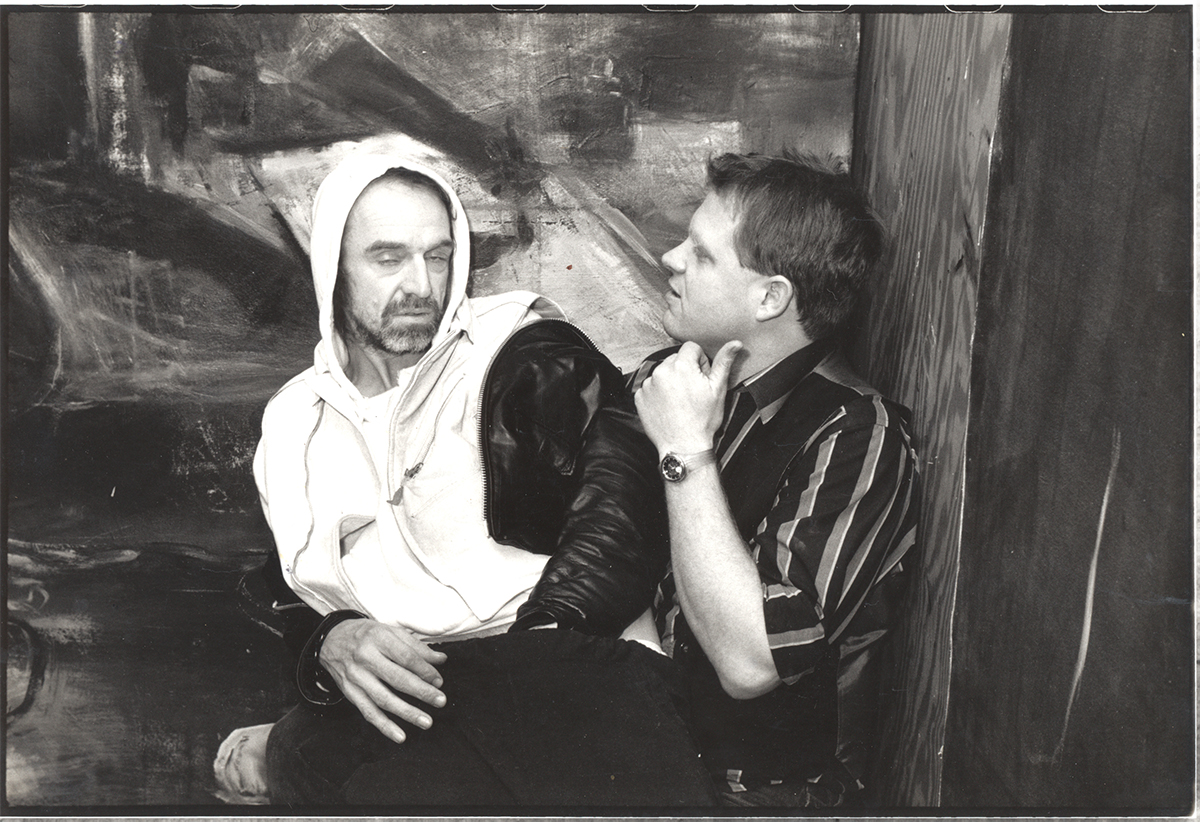

William Rand and Rene Ricard 1988, Rand Studio NYC 1988. Photo by Will Daley © Estate of Will Daley

William Rand, has dedicated his latest book, ‘Rene’ to the life of his friend, tumultuous artist and poet, Rene Ricard. Here he reminisces with Maryam Eisler about New York’s exciting community-led art world during the 1980’s and 90’s and his more mellow life now as he resides in Maine

Maryam Eisler: ‘Rene’, your latest book, is a form of diary of your East Village studio from the 80’s to the 90’s, with a backdrop of your friendship with the artist and poet Rene Ricard, set within an atmosphere of tragic events interlaced with street crime and drug addiction. Let’s talk about the shoe box time-capsule method you used for recording these events.

William B. Rand: I remember writing things down because the first time I did it, I couldn’t believe what was happening at my studio. It was so surreal; the drama and the fear around Rene was the most intense you could probably find in the whole of New York City.

ME: You have made references to a ‘safari’. Was it really the ‘jungle’ you have often referred to?

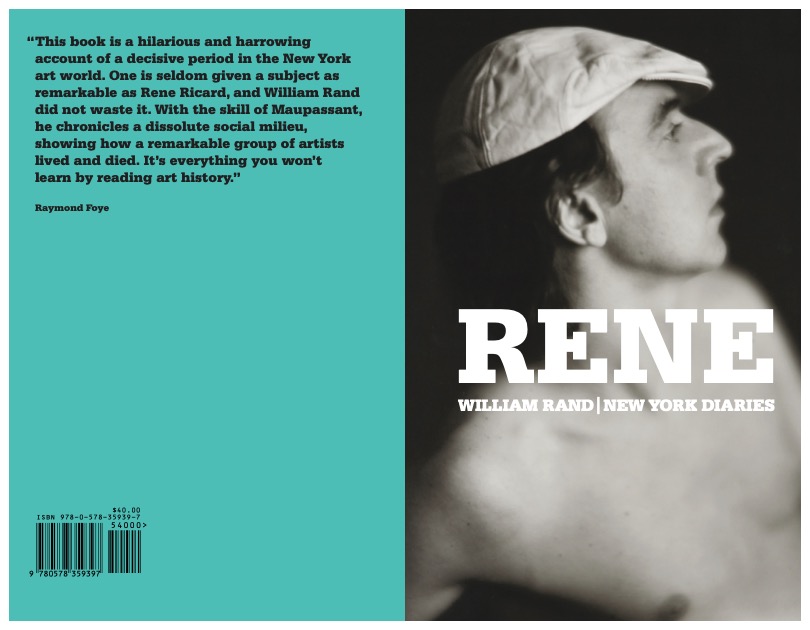

RENE book cover, front and back. Photo by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, quote by Raymond Foye, executor Rene Ricard Estate. Courtesy of William Rand and Osprey Press

WR: Rene himself referred to it as ‘Abercrombie & Fitch’! It was all so over my head really, that I felt like ‘ok I’m just going to write this down, because this is all too unbelievable for me not to write down’. The way Rene spoke, the order of his words, it was all so unique that five minutes later, he wouldn’t remember anything. So, writing things down as he said them was the closest way to preserving his rapid-fire complex communication – I just put them all in a box, and I certainly couldn’t let him know.

ME: What I found interesting about the time you are referencing is this sense of strong (artistic) community that reigned in New York City. Rene sometimes slept on the street, but there was a real sense of community that pulled itself together to support him … at times even paying him above normal artist rates, to perform, so as to keep his voice alive! In today’s art world, I don’t feel we have this same sense of artistic community and support. It may have been very chaotic then, on many levels, but to me, it seems like there was more authenticity in feelings, in compassion, in humanity, than there is now?

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

WR: Well, the people that cared about Rene could calm him down; Brice Marden and he had a very stable and authentic friendship; Brice is from the Boston area, as was Rene – they really understood each other. There were a number of us who were truly dedicated to him, and as Schnabel and other friends of his learned only too quickly, Rene loved being broke. ‘If he got $60,000, it would be gone by 5:00 pm, and Rene would be begging for cigarette money’ as Raymond Foye once said.

William Rand by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders 1982 from the series Art world. Collection of MoMA, and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas. © Timothy Greenfield-Sanders 2023

ME: Were there many other big names in the art world whose careers were strongly linked to Rene’s?

WR: Yes. Rene, for example, wrote about Francesco [Clemente] and it was used for a publication at Anthony d’Offay Gallery in London. Rene was the one person who could cut through everyone and tell them what he thought; they all loved his poetry, Clemente especially. Rene would often say ‘We’re going out, we have a mission!’ and I’d get dressed and go with him, and it was often on a very good adventure; sometimes, there was trouble lurking around the corner. He was a junkie but there was always this fabric of poetry, art and life behind it all, which made it both interesting and intellectually rewarding.

Debra Grid, William Rand. 16 canvases assembled, collage. All decades 32″ x 32″ © William Rand/ARS NY 2023

ME: Any stories of Ricard with Basquiat?

WR: I remember when gallerist Pamela Willoughby was living on Ave A over the Pyramid Club, in the 80’s, with my friend Hayne. One summer, Rene and Jean Michel were living in a tent across the street on Tompkins Square Park. They would always ask to come up and take showers, and Hayne would always let them in, much to Pamela’s horror. They would put on such innocent faces at the door- you had no choice but to let them in!

Rene was the one who said ‘Jean Michel doesn’t draw, he makes lists’. He would often talk to me about Jean Michel in his studio. He was heartbroken when Jean Michel died; after his death he famously went to a gallery opening of Jean Michel’s works, and placed a bottle of champagne on the table; it literally exploded! Rene believed in magic and he often referred to Basquiat as a saint. What Jean Michel became was the voice of inclusion for all the people that had been excluded to the party. He was a major movement-shaker for human change.

William Rand Maine studio 2017. Painted Collages. Rand Photo © 2023 William Rand/ARS NY

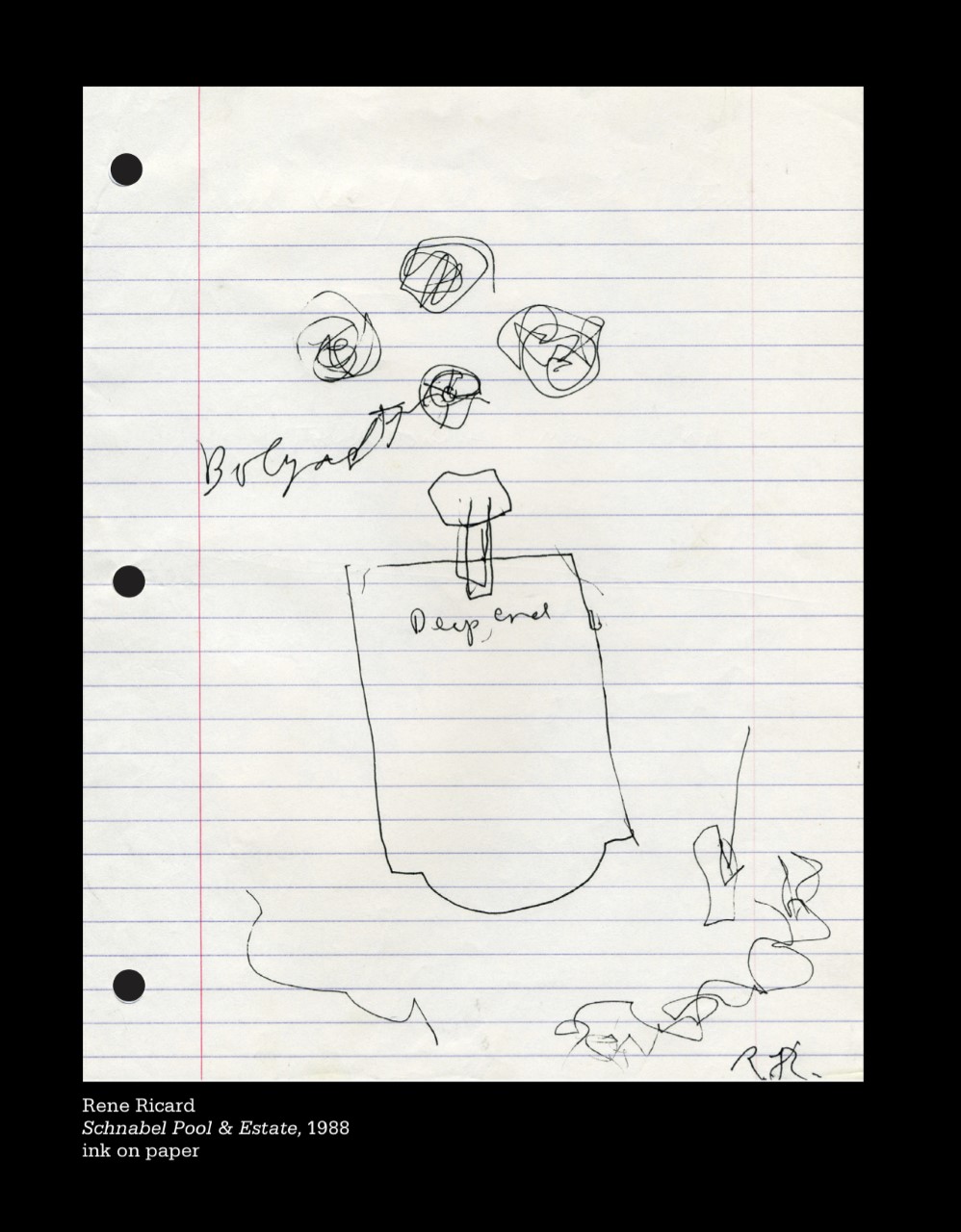

ME: Any memorable stories related to Ricard and Schnabel?

WR: Well, I asked him once if we could go and meet Julian and he said ‘that would take a papal decree…’ because – as you’ll read in the book – Rene had smashed up Julian’s car and he went to jail for it… in Rene’s mind, it was a very big deal. He had to wait a long time to get let out. I mean, Rene was drunk driving. Rene came in and out of the rain like a wet crow, I just held him as he sobbed and sobbed. Jean Michel was dead, his apartment across the hall from Allen Ginsberg had burned down, he was fired from Artforum, the eighties were shutting down hard. I was receptive to his pain. I think Rene did wonderful things for Julian; their work is highly connected and I would like to see Schnabel’s paintings hung with Rene’s paintings one day, because, love and war … well, they are connected. That’s a page of art history right there.

ME: What I find interesting is that whilst the book gives the reader a great insight into Rene’s life, I also think it projects a great picture of NYC’s subculture of the time, both high and low brow… the speed of the city, its psyche. I loved all the references to Warhol, to Edward Robert Brzezinski being rushed to the hospital after eating a Robert Gober artwork … All these funny anecdotal stories, above and beyond Rene’s story, yet all part of his world, and also yours!

WR: Exactly. That world, our world, was like a circus with so many rings going on … some of them were badly lit, and some of them were even less lit. I have to say when I left New York in 1996 to go to Europe, I brought the notes with me to Spain; that’s when I started transcribing them. And I said to myself, I don’t know what will happen when all the anecdotes are put in a row – will they breathe? I didn’t know what it would all do, but what had been a thorn on my side clearly became a rose.

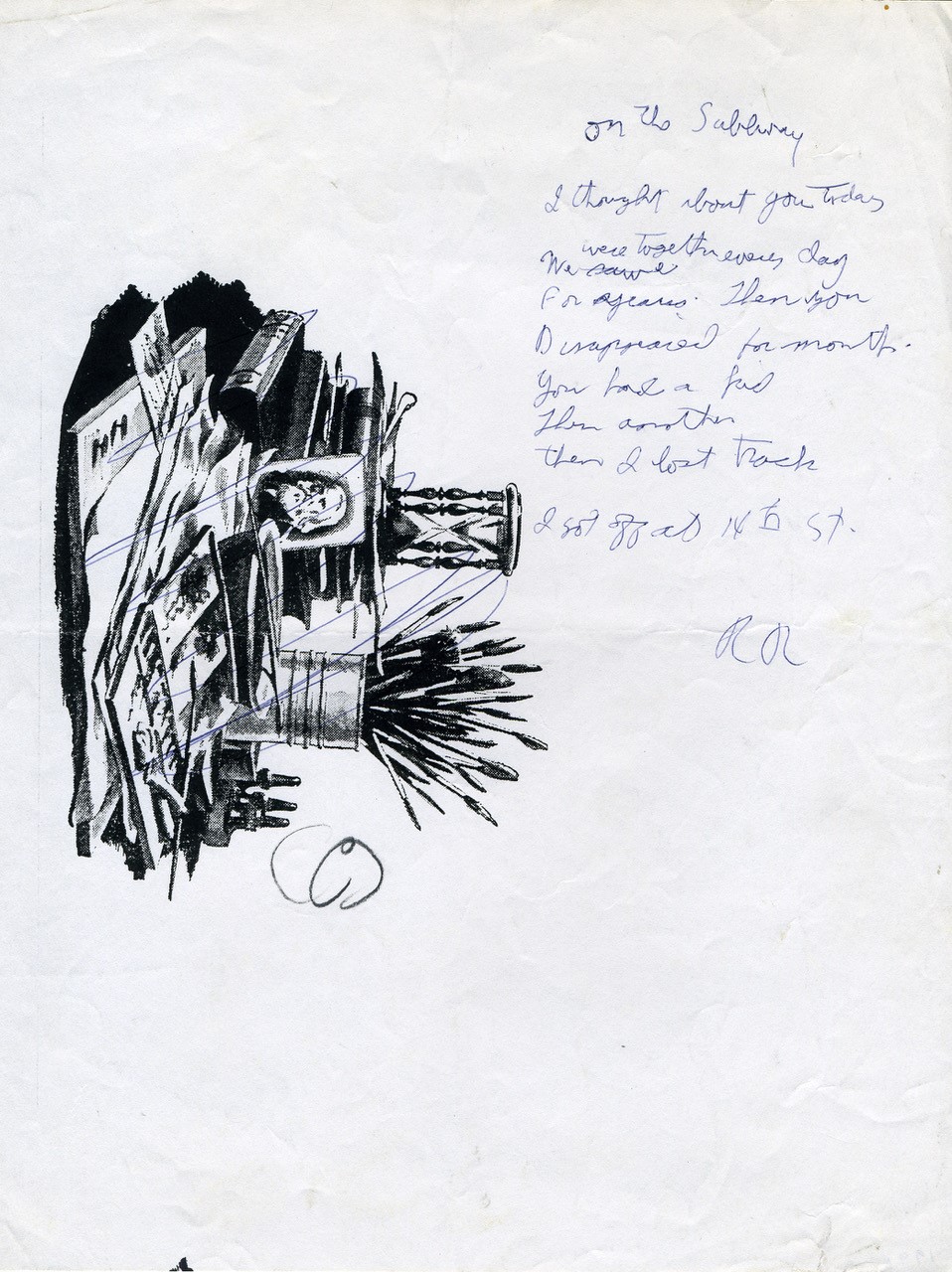

Rene Ricard ‘On the Subway’. Ricard poem 1989. 8 1/2″ x 11″ on photo copy © 2023 Estate of Rene Ricard. Courtesy Willoughby Gallery NY

ME: Well, it’s an amazing way of telling the story of a time, a space, a place, and a stellar powerfully charged bohemian within it all… a mover and a shaker, a real iconic operator. You get a real sense of New York, but also realise how much the art world has changed. How mould- breaking it used to be. I, for one, don’t feel that same sense of art pushing boundaries today. Society and the art world have become more clinical, more sanitised.

WR: To answer your question on the Rene front, most of the gallery people were scared when I walked in because I was so associated with Rene and well, things happened around Rene. And a lot of what happened around Rene was in very select areas, amongst the elite, in a very beautiful but dangerous atmosphere. His friends were Edie Sedgwick, Andy Warhol… and he had a very strong opinion of his position. Yet, Rene was sleeping on trains. Today, art and money go hand in hand – you can’t be a bohemian anymore in New York City. It’s all about the commerce.

ME: I think there was also less fear of judgement then?

WR: Interesting you say that. Yes. Rene came out of 60s street theatre. These are the people who stopped people in the streets, did things, provoked them, and that was very much part of the fabric of Rene’s life. Of course, now that’s all gone. That was very much the downtown thing, to attack the squares. He truly belongs to a different era.

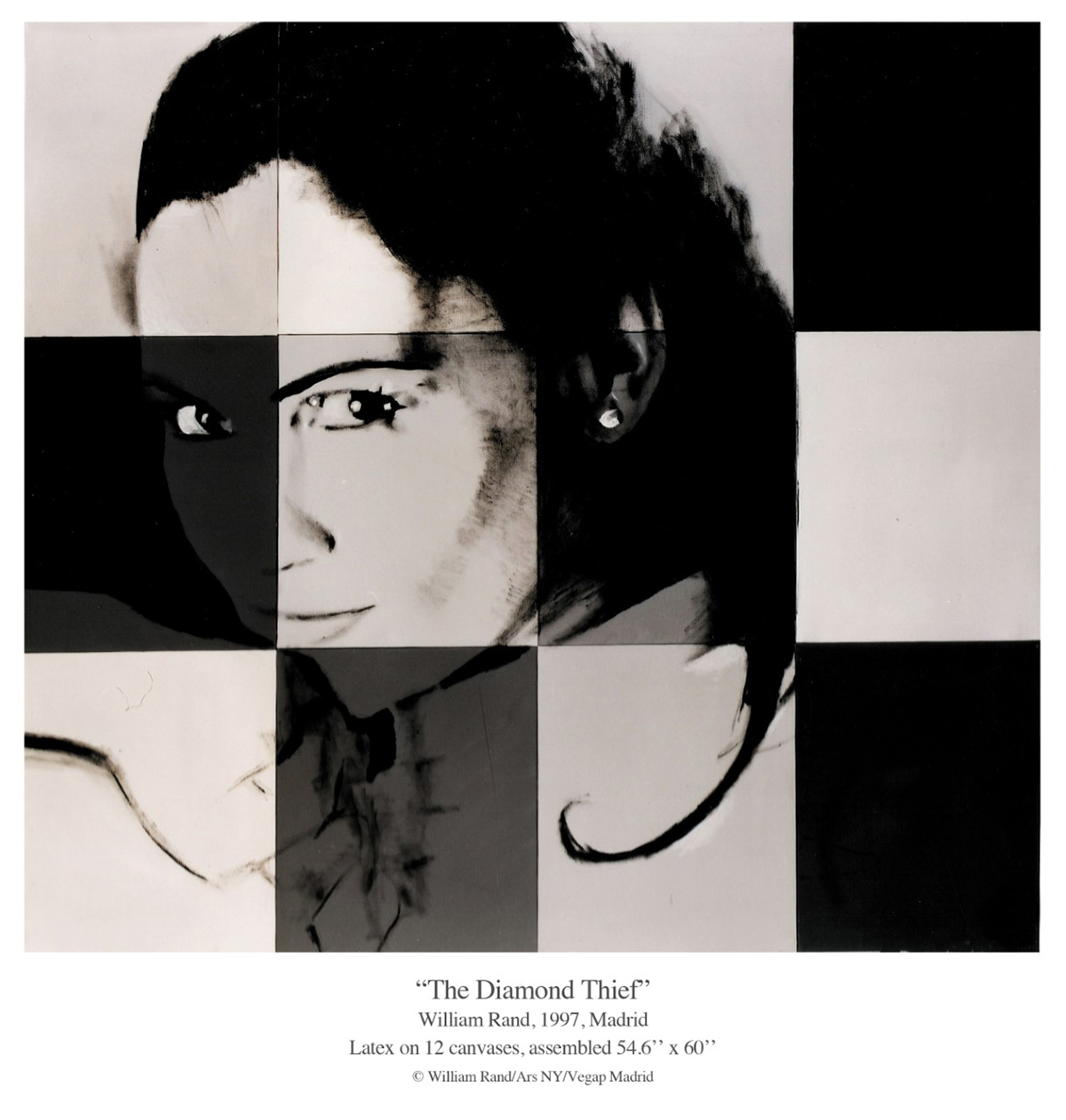

The Diamond Thief. Courtesy Willoughby Gallery NY

ME: Interesting that you were one of the only few people in Rene’s world who escaped this vicious circle of homelessness, addiction and trauma. You continued beyond that time, fruitfully, as a painter and a poet in your own right. Do you feel like you’re one of the lucky few who managed to escape that chaos?

WR: I left because somebody was going to get hurt. I also left New York in 1996, because the art world was very cliquey – who was in, who was out. It was just like Junior High!

ME: Let’s get onto your own practice – Peter Frank said that you belong to a generation of American artists ‘reared on images, on consuming them, on producing them, but not controlling them’. Do you agree with that?

WR: I grew up on black & white images.

ME: You were the first TV generation, right?

WR: Yes. Black and white TV, photographs, image reproductions in books… Records were also printed in black and white. So, yes, I agree with Peter because I would drown myself in thousands of images, looking for the one that calls itself the question, the one that did something, that hooked you, that engineered something.

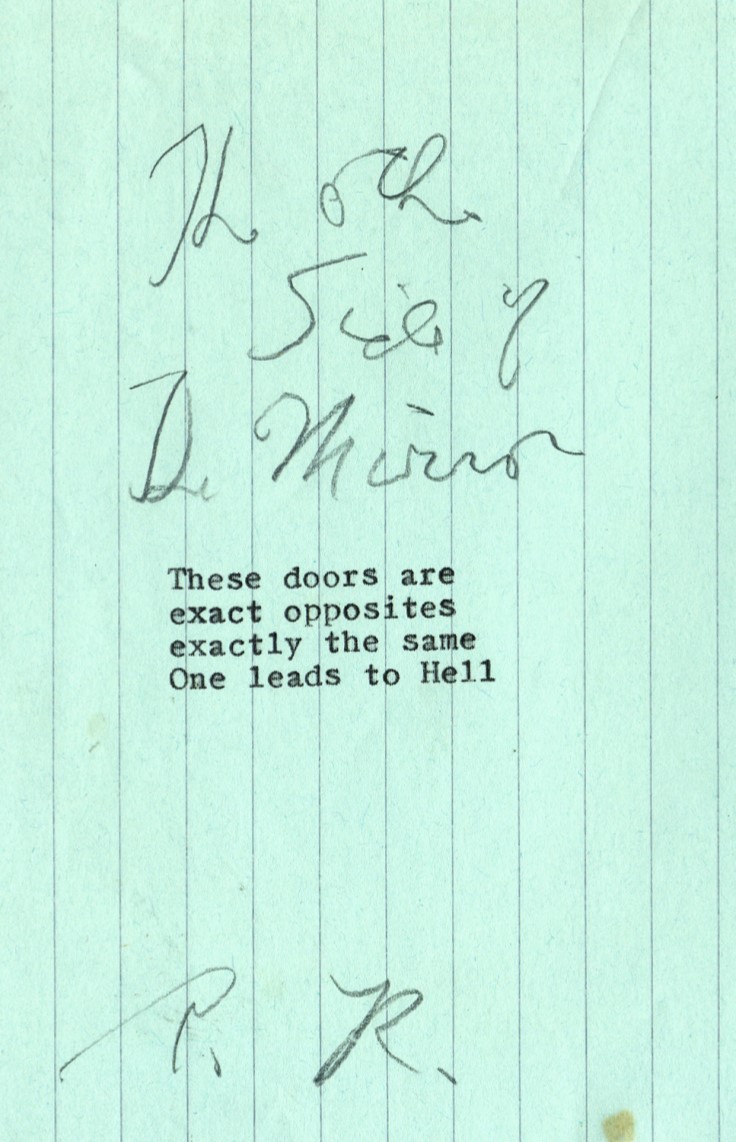

‘The other side of the mirror’. Poem by Rene Ricard 1988 3″ by 5″ on green lined paper, pencil and typewriter. © 2023 Estate of Rene Ricard Raymond Foye Executor. Courtesy Willoughby Gallery NY

ME: Much like your memories placed in a time-capsule, your artwork, adopts a grid format; you create a puzzle of images and thoughts, and then you recreate a narrative out of it all. Tell us about this approach to your work?

WR: Yes, I make the grid. The viewers then bring their narrative to the artwork; they make up the story.

ME: It’s like hanging your psyche on the wall, but you ask the viewer to make sense of it?

WR: The grids are modules so they can be combined in any shape or form you want… each slot can be combined; I find this process fascinating and I continue to explore the process. I have grids and grids and grids, 4ft by 4ft, 5ft by 5ft… they’re my notes and I love them. I particularly love what they can say.

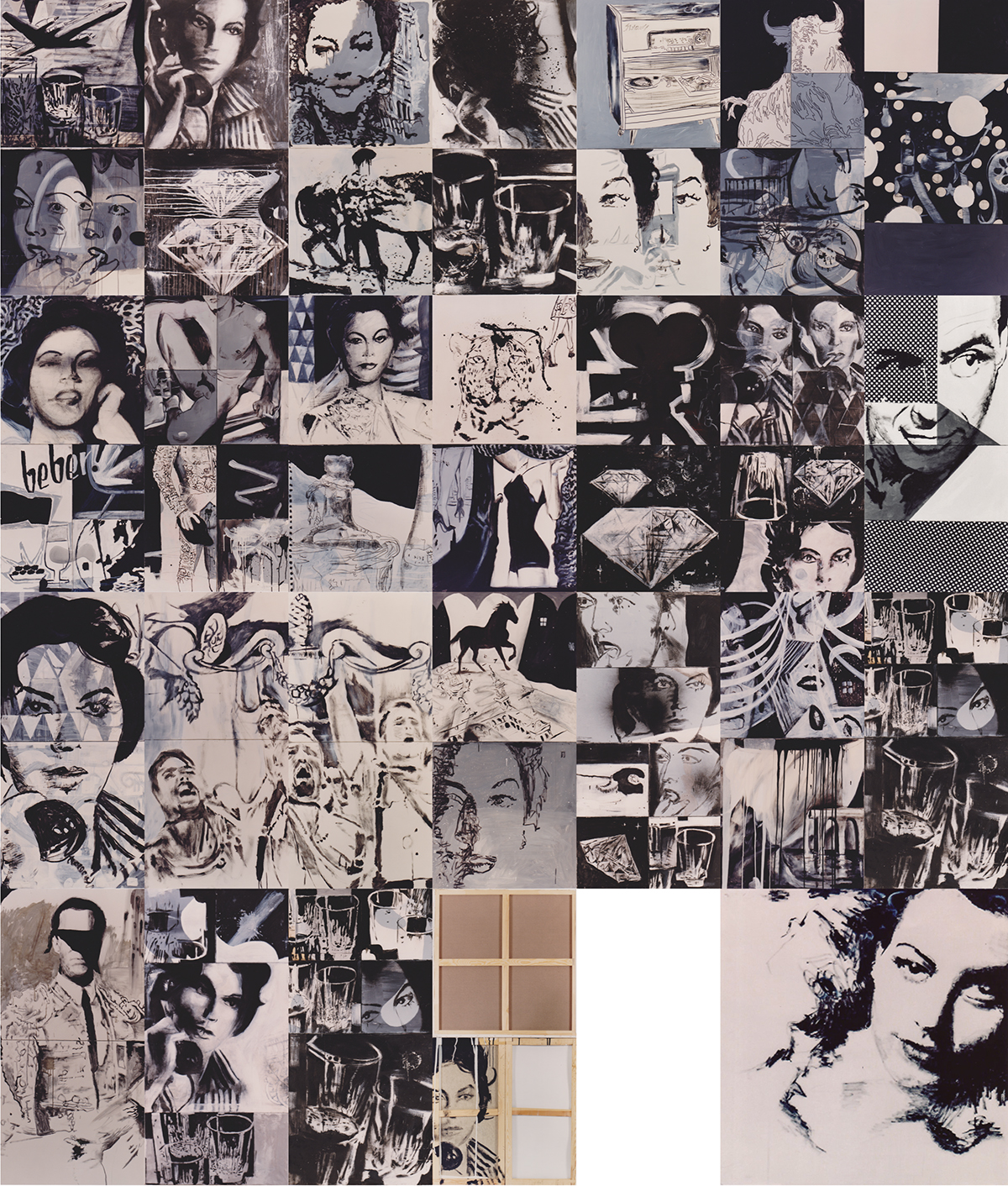

ME: Let’s now switch to your 90s modular ‘Ava Gardner’ grid mural, an assemblage of painted canvases brought to life through a collaboration with poet Richard Millazzo… letters, poems, photos and paintings…much of which is based on your conversation with the concierge at the Madrid Hilton Castellana hotel, a man who lived through much of the Ava Gardner narrative you exposed. Talk to me about this project and its inspiration. Is it a form of Ophelia sinking into dark waters?

WR: Well Ava Gardner came to Madrid, when she ran away from LA and Las Vegas, Sinatra and the guns. She loved Spain. She was pretty wild. She had the gypsies over all the time, they’d steal all the silver, all the furniture but she didn’t care – they would stay till dawn!

The Modular Ava Gardner 2000-2002 Madrid, William Rand. 54 square metres, assembled, mixed media on canvases. Exhibited at Galeria Najera Puerta Alcala 2002 Madrid. Essay by Richard Milazzo © 2023 William Rand/ARS NY

I have lots of notes of her antics jumping on beds, running up and down the hallways naked, ringing up the reception ‘Oh I see you have a new bus boy, could you send him up right away…’ She went through the whole staff! The worst thing was how the piano went off the balcony… and the desk rang up and said ‘Excuse me is everything alright in the room?’, and she [Ava Gardner] said everything was fine, then the front desk said ‘We see the piano has gone off the balcony, would you like to explain?’ and she turned around and said, ‘As you can see gentlemen, this is the finest and most expensive suite in Spain, and we are used to the best. The piano was not good enough, so we threw it off the balcony – it was out of tune!’

I unveiled my Ava project in ‘The European’, this magazine back in the 90s which was in every Ritz hotel in Europe. The American Embassy people came to my opening. Funnily enough, the opening was two days before the one year anniversary of 9/11. The embassy had set up a huge ceremony for Americans, with military bands, speakers… but guess what? My Ava Gardner project took up all the press in the whole country. The embassy said: ‘You stole our press for 9/11! You stole our show!’ But in fact, they were happy for me.

Raymond Foye Executor © 2023 Estate of Rene Ricard

ME: What took you to Spain in the 90s in the first place? Why not Paris, why not London?

WR: In the 90s, I had met a lot of Hispanic people in the East Village through the festivals. They would pray to the Virgin Mary and drink beer at the same time! And I said to myself, these people are very relaxed about it all! I also got involved in the Hispanic scene on the Lower East Side. When I arrived in Spain, I didn’t speak a word of Spanish – I had to learn it on the streets. And I didn’t really know anybody but I saw these drag queens, and thought to myself, ‘If I want to get ahead in Spain, I may as well hang out with these people’, so I introduced myself. They then introduced me to all the movie people, and I immediately had a peer group.

ME: Talk to me about your ‘Les Affiches’ project. Affiches were big during the Belle Epoque period in Paris; they were used to advertise military recruitment, political opinions, advertisement etc. What did they mean to you?

WR: It was funny; one of the last things Rene said to me before I left New York, was ‘You know, you would make a great affichiste !’ – I’ve always loved posters, I’ve always loved graphics … the Russian Revolution… the Black Panthers… flat areas, letters and images with volume… Graphics are what move you… they are punchier than art. ‘Les Affiches’ is very much about war, and the price women pay in war; it’s about the spirit of resistance, socio -politically and culturally.

Les Affiches, 2017-2019, Mixed Media on Wood. Courtesy of William Rand Studio

ME: It seems to me that although there’s continuity in your work, there’s equally a referencing to the past, a continuous dialogue between today and yesterday?

WR: The eternal present.

ME: What are your current concerns?

WR: I’m obsessed with painting with linseed oil, the house smells so wonderful! I love the shiny black surfaces in my new work … I guess I would just say that moving on and continuing is the best reward and inspiration.

ME: And not being afraid to try new things – is abstraction your new frontier?

WR: It’s actually something I never get to do; abstraction is so fun because it’s so different from realism. I’m doing some paintings of the surf at night. I’m interested in the materiality of things, and I’m really not getting too hung up on the images themselves.

Guitar player in the surf, 2021-2023, William Rand

ME: Would it be fair to say that you belong to the fluxus generation, with Marcel Duchamp being a forerunner of that movement?

WR: That’s a very good question – it is precisely what I’m doing.

ME: It’s reductive and it’s meditative.

WR: Very right! Albert Fine saw me painting in art school, French interiors, and he said ‘this is not going to do, we’ve got to take some responsibility of you.’ And he went to the art shop and came back with this black spray paint. And then he said ‘I want you to start going to New York, forget about what they’re teaching you here, none of these colours are permitted; what they’re doing to you is criminal and we have to get you back’. So, I got involved with new materials. I hid the work I was doing with Albert when the professor came around. If I hadn’t met Albert, God only knows what I would have turned into!

Read more: Joel Isaac Black: The Coolest DJ In The Alps

ME: Please share your last memory of Rene.

WR: I saw him at the Chelsea [Hotel]; he had just had a show with Ronnie Wood in London. He had a brooch on, in the shape of a pirates’ skull, encrusted with a big dazzling jeweled eye, probably a ruby. He had received a lot of money obviously and had acquired all these fancy things. We were excited to see each other; it had been a long time. But it also brought back memories of why I left the scene.

Wherever there was cash there’d be crap, parties, degeneracy, and as long as there was cash it would just go on for days, Rene and whoever he got involved with. That was the danger. That’s why I left.

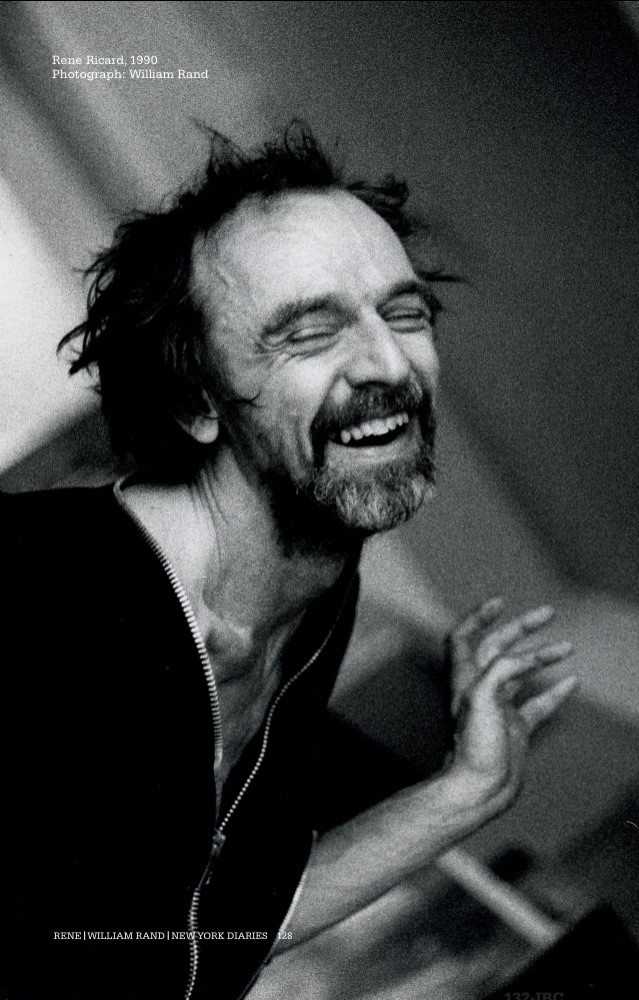

Rene Ricard, 1990, photograph by William Rand

ME: Now you’re back in wholesome Maine, are you happy?

WR: Although I had my parents die, my husband die, and I was very sad, I had learned how to read as a child in Blue Hill [Maine], so I decided to move there. This 1840 house was the town funeral home; no one would buy it and it was sitting there for years, empty. I said to myself ‘I’m getting it’ and I truly love the house – the chapel, the front rooms, this and that… I have a private park of four acres, and I’m writing and painting, and couldn’t be happier.

ME: Are you still using the same method of putting ideas in a box?

WR: Oh yes – people tell me so many things and I go home and write them down and put them all in a box.

ME: Any exhibitions planned?

WR: Yes, I have an exhibition and artist-in-residence week late September 2023 at the new Willoughby Gallery in Southold, on the North Fork of Long Island. Pamela Willoughby is an art world veteran, and this new gallery is unique and very cool. Southold is different from the Hamptons, so that is very attractive.

Find out more: