‘Atelier’ (2014). Thomas Demand.

German photographer Thomas Demand has become celebrated for his compelling, sometimes shocking, abstract recreations of the everyday. He talks to Anna Wallace-Thompson about the homogenization of our worlds, finding power in the banal, and Saddam Hussein’s kitchen.

Thomas Demand

There’s a particular moment of calm – let’s call it suspended time – when things have settled down while still retaining the memory of the movement that filled them a split second before. Think of the moment when that last dust mote finally settled after drifting down a shaft of light, or the ghostly echoes of the last flutter of a piece of paper as it relaxes into place. Or when you don’t know if the door just slammed shut or is about to burst open. Or sensing the presence of people only through their absence. That’s the moment German photographer Thomas Demand is interested in.

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

In fact, at first glance, Demand’s photographs appear simply to be snaps of ordinary places, unremarkable for their sameness, from half-empty supermarket shelves to a bath awaiting its occupant. (This is something that struck him about modern urban spaces, particularly when he first arrived in the US.) Yet, these seemingly humble snaps of everyday situations have earned him a place in the collections of international institutions such as the Guggenheim and MoMA. At auction, his works have sold for more than $100,000 at Christie’s, and he was included in the sale of Mario Testino’s personal collection at Sotheby’s, alongside luminaries such as Wolfgang Tillmans, Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman.

‘Hanami’ (2014). Thomas Demand

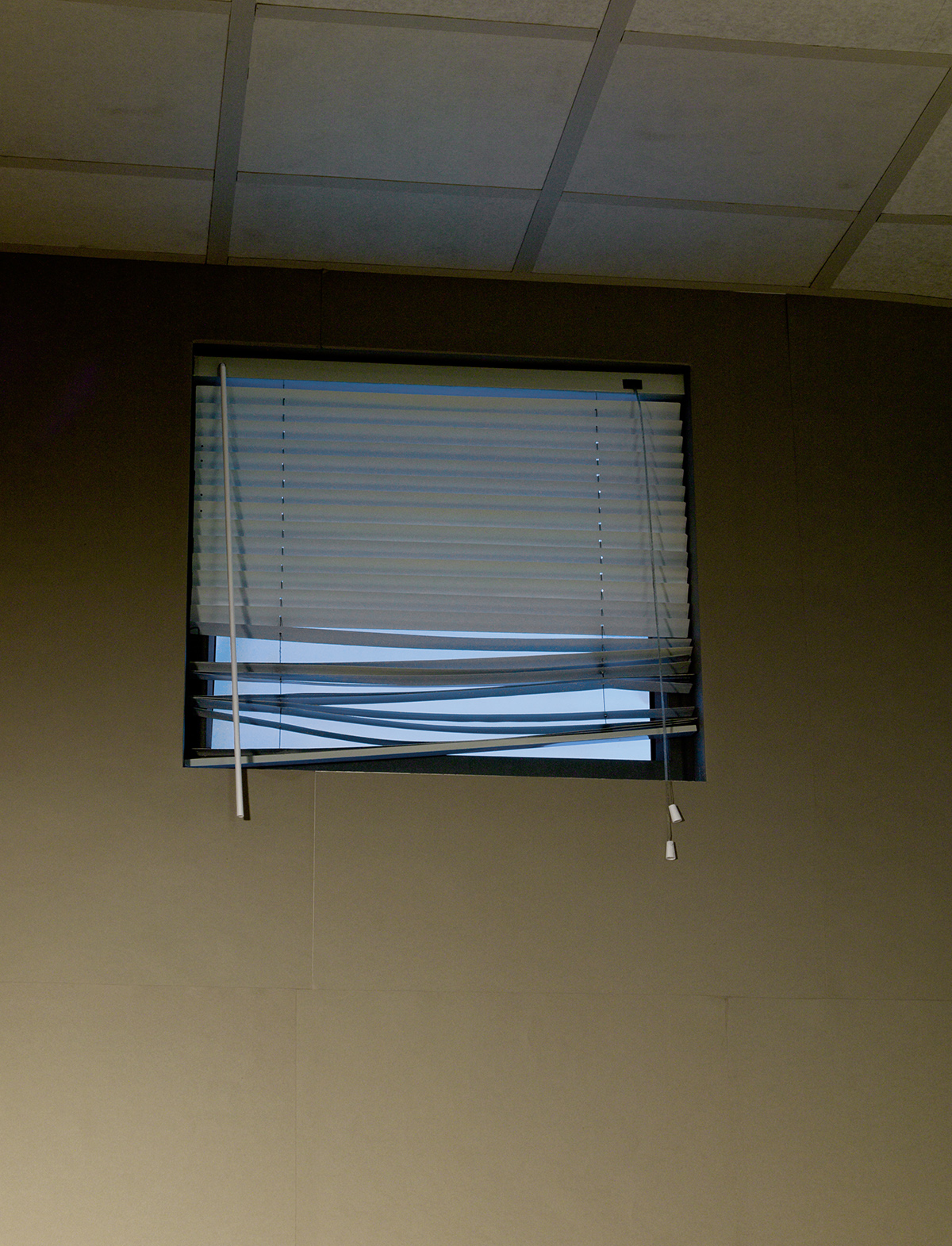

So what is it about these seemingly everyday snaps that has everybody so hooked? Well, further examination reveals each portrait to be a meticulously built paper recreation. Yes, paper. Working in often quite large dimensions, Demand reconstructs the most complex real- life scenarios out of the humblest of materials. They are perfect – or rather, perfectly imperfect, for at the heart of Demand’s work is an interest in the world as a filtered rendering – that is, the paradox of examining past moments through the lens of the present – and even then, through a canny reconstruction of that original moment. “Perfection and beauty are very often seen as interchangeable,” says Demand. “However, if something is too perfect, then it becomes sterile.” And so, working from found photographs of banal scenes (be they supermarket aisles, hotel rooms or office interiors), Demand meticulously reconstructs these tableaux out of paper – warts and all. It is these sculptural paper sets – often quite large in scale – that he then photographs, imbuing the finished image with such an uncanny realism that the eye is often fooled into believing it is looking at the ‘real deal’.

‘Folders’ (2017)

“What I have been doing over the years is replacing the time frame of the [original] photograph with another time frame, which is no less a point in time,” explains Demand when we speak. “The original scenario in the media photograph may no longer be there to look at – although it may be from an event that is still in our short or long-term memory, depending on when it was taken. What I suppose you can see in my work is a paradox of time standing still that is both my own fragile paper construction (complete with all the little imperfections and details of ‘reality’) as much as it is a memory of the moment captured in the original photograph.” The sense of transience in Demand’s work is further compounded by the fact that he often discards the sculpture itself (and, in fact, originally began photographing them purely for the purposes of documentation).

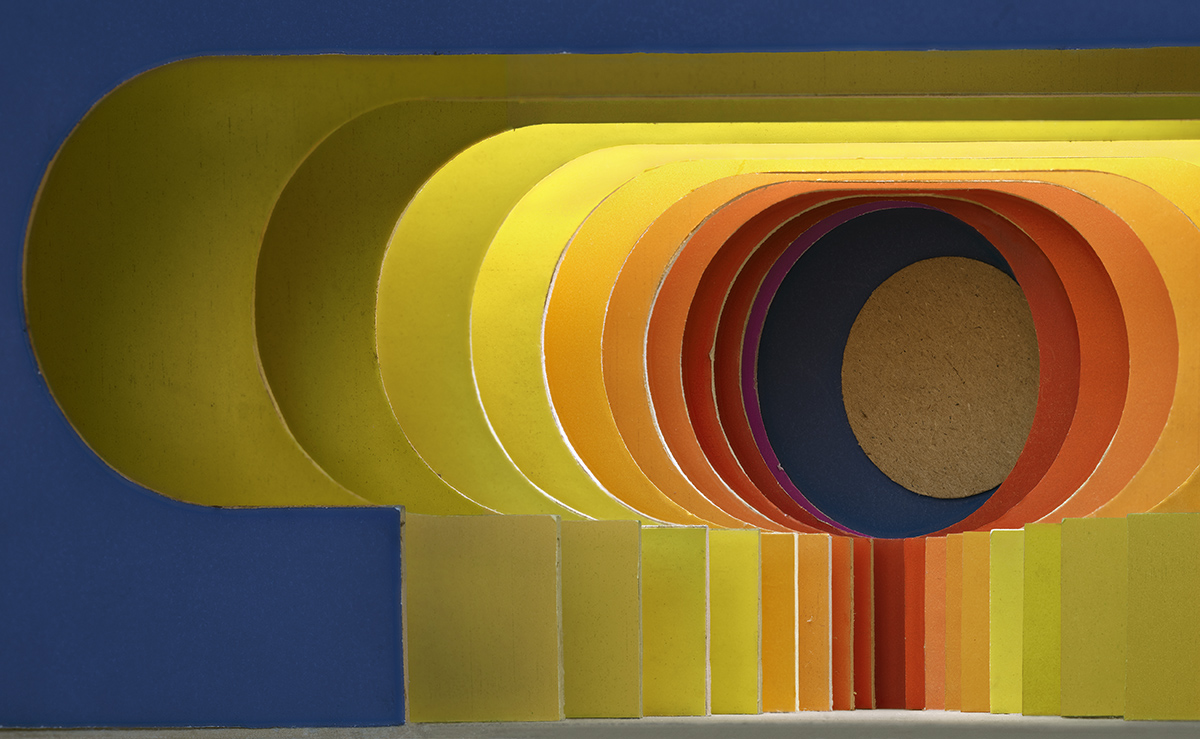

‘Rainbow’ (2018)

In person, Demand is more tidy professor than wild-child artist, his neatly trimmed hair and beard perfectly in sync with his nifty vest and jacket. Get him talking, however, and you can almost hear the thoughts galloping inside his head. When he gets going, he talks a mile a minute, as if the thoughts inside him were moving faster than his ability to articulate them. They tumble out almost in a stream of consciousness, except just when you think he might be going off on a tangent, like a master conductor, Demand deftly brings all the threads together, eloquently and precisely articulating his point.His powers of observation, too, are key to the vision behind the work. Growing up in Munich in the 1960s and 70s, it was when Demand visited the GDR that he first began to pay attention to the power of mass production (or, in the case of the GDR, the lack thereof), and Warhol’s Brillo boxes, for example, remain a key influence: “I grew up in Munich, which is in West Germany, which had plenty of everything.”

Read more: Why we love the New Perlée creations by Van Cleef & Arpels

As a young artist, travels and study followed – Düsseldorf, Paris, and Goldsmiths in London – as well as the US (he is now based in both LA and Berlin). During this time he began to notice what he refers to as global “homogenization” – a hospital ward in one part of the world looks very much like it does anywhere else, for example, and, with our mass-produced products – be they Nike trainers or even the Tupperware found in Saddam Hussein’s kitchen – we are more united than we think. “When they found Saddam, and showed the photographs, there were so many remarkably recognisable objects,” says Demand. “In one way, it’s the devil’s lair, but in another, it’s possible to see it in parts as your own kitchen. Maybe it’s a little dirtier, but he had the same objects as you and me.” The resulting work – Küche/Kitchen (2004) – could truly be a picture of a kitchen anywhere. “It’s funny how far objects circulate worldwide: you look at photographs of upheavals in Africa and people are wearing the T-shirts of a local bank in Texas, or plastic sandals made in China and marketed in California can end up in Ethiopia. I am fascinated by how the everyday links us to other cultures, from the pervasive blue computer screens that illuminate of office buildings out of hours, or the industrial slickness of an airport.”

‘Küche/ Kitchen’ (2004)

‘Daily #16’ (2011)

As well as the tableaux of media images that he is known for, Demand has experimented with more intimate scenes familiar to social media. The ongoing ‘Dailies’ series begun in 2008 features an ashtray, a plastic cup shoved into a chain link fence, or even a leaf about to fall through a sewer grate. “I was looking at doing something shorter and easier,” he says. “We all have cell phones in our pockets, and the images being circulated are now private photos – subjective little notes that might not make the news, but are still a form of communication and a culture in itself.”

Read more: In conversation with Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson

These ‘smaller’ works also offer a welcome break from larger and more ambitious set- ups. “In a good year I can make five works, but in a bad one just one,” sighs Demand. “Also, working occasionally with a team of 30 people means that if you’re two months into a particular set up, it’s too late to stop, so you keep going until it works, there’s no way around it.” For example, the work Lichtung/ Clearing Demand created for the 2003 edition of the Venice Biennale took months to get just right due to it being displayed en plein air, and therefore needed to be in some harmony with its verdant surroundings, the challenge being that the Venetian foliage kept changing with the seasons while the image was being built.

‘Daily #15’ (2011)

They leave things open – can you imagine how they might they be reused for something else?” This is particularly evident in pieces such as Rainbow (2018), part of ‘Model Studies’, in which abstract circular shapes in a range of yellows, oranges and reds hint at the full potential of the building they might perhaps one day have been, yet also present themselves as abstract colourscapes.

Most recently, Demand has had a major monograph published. The Complete Papers presents a survey of his work over three decades, and proved to be both a challenge as well as something of an eye opener, as he was able to see an evolution in his work that he had never noticed before. “I thought I was pretty organised, but it turns out there were so many pieces I’d forgotten about – and now that the book is out, there are so many more pieces I realise I would still need to add,” he laughs. “I can see that my work, since the beginning, has been moving slowly towards abstraction, though photography and abstraction can be a bit of a bad marriage in that photography, by its very nature, is figurative.” So what’s the endgame? “If my work were to become too abstract then it would all become a pointless exercise. To be something, the image has to stay on the very edge of nearly becoming something.”

Find out more: thomasdemand.info

This article was originally published in the Summer 19 Issue.