Iris Study No.7 18 x 26cm Oil on Canvas

Artist, W.K. Lyhne speaks to Maryam Eisler about her latest body of work, Stabat Mater, where she explores the treatment of the female body throughout history

ME: Can you talk to me about how the concept of post-humanity has informed your latest project?

W.K. Lyhne: As you know, Humanism as a concept emerged at the time of the Enlightment, that Man was at the centre, instead of religion. Man was the measure of all things and this was exemplified in Da Vinci’s image of the Vitruvian Man. But the concept of Man excluded more than it included. It was defined by what it is not. It was not, the racialised or sexualised ‘other’, it was not people of colour, people of sexual difference, Jews, children, animals, the disabled, women. There are two examples at the time, often cited, that show this so well. The French writer, Olympe de Gouges, part of the French Revolution who responded to the Revolution’s Declaration of Human Rights of 1789, by writing the Declaration of Women’s Rights in response. The regime guillotined her almost immediately. Another example is from a biography that I’m reading at the moment of a man called Toussaint Louverture, known as the Black Spartacus. He was involved in the overthrow of slavery in Haiti at the same time as the French Revolution. He was imprisoned by Napoleon and died in captivity. We are all equal, but some more than others.

W.K. Lyhne photographed by Maryam Eisler in her studio

When you came to my studio we spoke about Mary, who is given to women as a pedagogue of what women should be: this passive, two-dimensional, non-complaining, virtually mute figure. Mary speaks four times in the Bible.

Marina Warner, says Mary is ‘alone of all her sex’ and this is accurate. She’s not male and she’s not really female. She never processes through the normal animal functions of women. She doesn’t have sex, she doesn’t menstruate, she doesn’t age, she doesn’t perspire, she simply doesn’t change – exactly the same static figure all her life, biddable and mute. Yet she remains the ultimate woman and mother.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Alongside this I’m looking at animals in art that are supposed to represent ‘us’ – our mortal selves. But what is this humanity the ‘us’ that they are trying to represent? Often they are done through the agency of the Church. Like the Flayed Ox , meaning Christ, done by many artists, Soutine, Bacon, Rembrandt, Saville, and the Lamb of God, also Christ, Van Eyck and Zubaran. For this I’ve been looking at actual sheep, the lamb, through this lens. In my recent work is connecting the anachronized figure of Mary with the anachronized image of the lamb.

Once Upon a Time (Met Him Pike Hoses)

In the case of Mary, it’s a patriarchal story designed to oppress. The cult of Marianism is very much admired in countries where docility, passivity, and service to your man, whether that’s your priest as a nun, or your husband or your father, are admired. In many Catholic countries, these are espoused as ideal characteristics for women.

Once Upon a Time (Met Him Pike Hoses) detail

In the case of the lamb, I’ve noticed when you look into a field of sheep they are not just sheep, they are a field of ewes. Of mothers. Have you’ve seen a ewe with its fluff removed? Sheared they are very mortal looking. Matronly, exposed and not at all like the furry shorthand of sheep at all.

Photo by Maryam Eisler

ME: Talk to me about religion.

WKL: I’m not religious. I used to believe in God, I think I used to believe the whole religious story. I don’t anymore. I did believe there was a maker at some level. But last year in Greece on a residency at the British School, I looked closer at other stories from earlier cultures. Isis, Osiris, Cronus and Rea, Baucis and Philemon etc. All the stories are so similar to our own bible stories. Ours, like theirs, are just a version.

What interests me in the image of the animal in the Lamb of God, is that it has not changed since Roman times. It hides in plain sight. It’s on menus, it’s on football shirts, it’s everywhere, but nowhere. It’s part of our visual vocabulary, but what about the animal behind it? The image moves from livestock to Church pin up, like Mary, a girl of Galilee to the Queen of Heaven. What is the meaning behind it? In the case of Mary, it’s a patriarchal story designed to oppress women. I fail to see how anybody could not be interested in religion, in the sense that these things inhabit our collective and national consciousness. They’re all there, where you’re aware of it or not, they never go away.

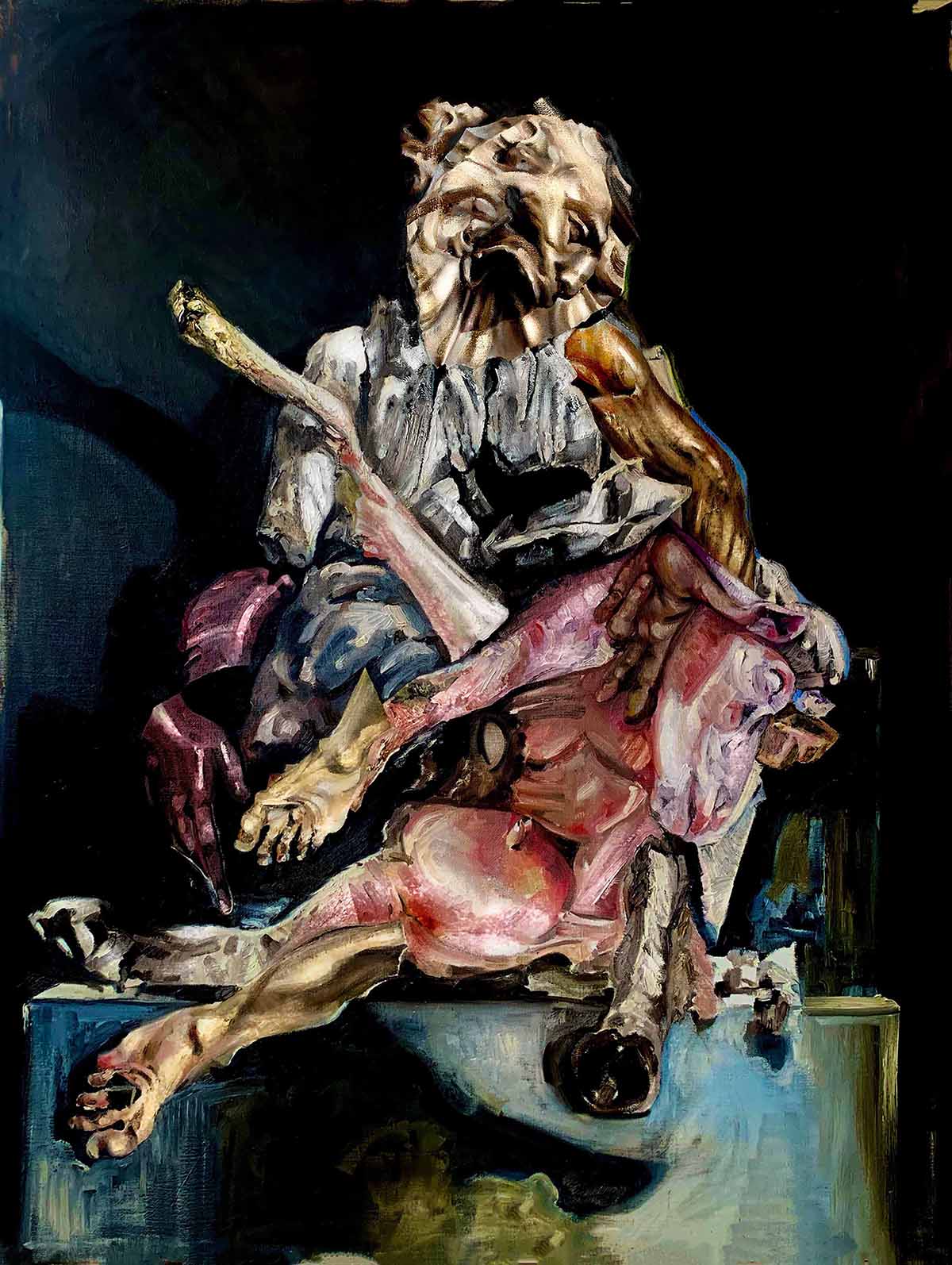

Stabat Mater 111 (John Moores) 120 x 160cm Oil on Canvas

ME: It’s very inspiring and you could aspire to it, but then the underlying factors are something different.

WKL: Yes, it’s exactly so. And it’s very seductive. Religious imagery and sacred music accompany you at some level from birth to death. They are very comforting and at ceremonies they offer the element of sobriety. The music particularly is incredibly beautiful and it has such credibility. People want to believe in something.

ME: I think there’s that: fright and hope. I always say religion, gives you hope, and it also frightens you from doing something that’s not right in case you get punished. I suppose it keeps you in the straight line.

WKL: Agree. It gives you a place to occupy, certainly. Rituals to navigate the unrelenting chaos that is life. I’m looking currently at Aby Warburg, the German art historian, who created this idea he called pathosformel . This he intended to mean the emotionally charged visual trope that recur throughout images in Western Europe. The idea is that certain images have a shorthand to connect with feelings, a visual mnemonic if you like. I am trying to see if it’s possible to find a new pathosformel , that represents some of those things that are excluded from the definition of humanity. This is not men-bashing or even only feminist – I looking for something more complex, something more nuanced, I guess.

Photography of W.K. Lyhne’s studio, in the home of one of her collectors, by Maryam Eisler

The Age of Enlightenment Man has the poster boy of the Vitruvian Man. Vitruvius – the heteronormative, able-bodied, ethnocentric, handsome, young, powerful man – who stands outstretched, in his symmetrical nakedness. This image of what “human” is, has now left the bounds of this earth. It is sewn onto the uniforms of NASA‘s astronauts and it flies on the flag on the moon.

ME: It’s interesting that they’ve chosen that to put on the moon. Who have they put that for? It’s a representation of mankind but not humankind.

WKL: Yes, very much so. We need images that are more enabling, more complex. The pandemic showed us more than anything else, we’re all in this together. But we’re not the same. There are people without sanitation, girls without education, people without rights. The voiceless, the unheard. I’m very interested in this idea of voice and the scream that can be seen but can’t be heard. That is some of what the triptych at the Zabludowicz Collection are about. These and other one, in the John Moores Painting Prize shortlist, are also connected with the unrecognisability of relationships within the maternal framework . How despite a child being from your body, the relationship never settles, can be often disjointed, always in flux. But as always it’s also about the possibilities and suggestibilities that paint can offer.

The triptych on display at the Zabludowicz Collection

ME: Are you showing whole triptych at the Zabludowicz Collection?

WKL: Yes, until 25th June.

ME: Talk to me about that wonderful image of Jesus. The long one and your versions.

WKL: That is a painting by Hans Holbein the Younger, done in 1521 and its hangs in the Kunst Museum in Basel. Last year, it was 500 years since it was done. Holbein represented an incredible departure from what had gone before – he’s a very fine painter. Some people believe it was a predella, the section at the bottom of an altarpiece and that’s why it’s long and thin – one foot by six feet, thirty by one hundred and eighty centimetres. I just prefer to think that Holbein decided to make this incredibly controlled environment using a long piece of wood for a painting surface – an enclosure, where this piece of corporeality was going to exist and that corporeality was the corpus of Christ. The Christ you’ve killed. The dead man. The squashed man. The emaciated man. The human man. There was a lot being written about the fact that he was just like any man and not sacred enough. I don’t know if you’ve seen the Donatello exhibition in the Bargello. It’s now on at the Victoria and Albert Museum, but I saw it in Florence last year, and there’s a great fuss at the time at Donatello’s wooden Christ didn’t look ‘Christ-like’ enough. He was too ordinary. Brunelleschi said, like a tradesman and not holy enough. And there were similar concerns over the Holbein Christ; he got a corpse and worked from that – all too human.

Photo by Maryam Eisler

I became very interested fabric during the pandemic – I did this program to support a project of the charity Action Aid, they supply sanitary products to vast parts of the world, particularly Africa. One of their projects addresses period poverty. Half the population of the world menstruate, that’s how we procreate the species, but for too many, it’s considered problematic, disgusting, full of shame, stigma.

During lockdown, when we were all kind of sent home and we didn’t know what to do with ourselves in our domestic environments. The fabric of what surrounded you took on a new importance. Fabrics are concealing, revealing, inside the body, outside the body, covering up for it, it’s quite a female concern. I started to paint these fabrics, ordinary everyday fabrics of the home, worn thin by wear and touch, on cotton rag paper, also blobby and worn. The paper made in India by a programme called Khadi. These start with ragpickers – women generally – who take the discarded fabric and bleach them with peroxide to make paper from them. The oil leaked out of my paint onto the cotton paper, all speaking to the materiality of the project and subject matter. The idea, called On Rag (an old-fashioned British term for having a period) was circular: I painted them on this cotton rag paper made by women and sold them and the money went to buy paper products for women in.

She Banks Down Fire (after Hans Holbein the Younger)

That was the project I was working on when I decided to paint a version of the Holbein. Working away from a studio meant working in the bedroom. In London I sleep in a box bed. What is shown in She Banks Down Fire is my own box bed, underwear, used tissues, discarded knickers, damp towels. Holbein’s Christ has a dark blood caked on a wound made by a spear, mine the more humdrum monthly sanguine staining. The ridged hollowness of Christ’s ribcage, are the spines of underwire, the stiff black hair, is see-thru nylon.

Simone De Beauvoir says that women are made from Adam’s supernumerary bone, that humanity is male and man defines woman not in herself but as relative to him. He is the Subject , here like Christ, she is the Other. Jonathan Jones, the journalist from The Guardian, wrote about Holbein’s Christ that there is nothing Christlike about this body, nothing to set it apart. It is anyone’s corpse. But as you know, this is world in which the women all live, all women, every month, every child is a reminder of the mortal, bloody, messy, fleshy real.

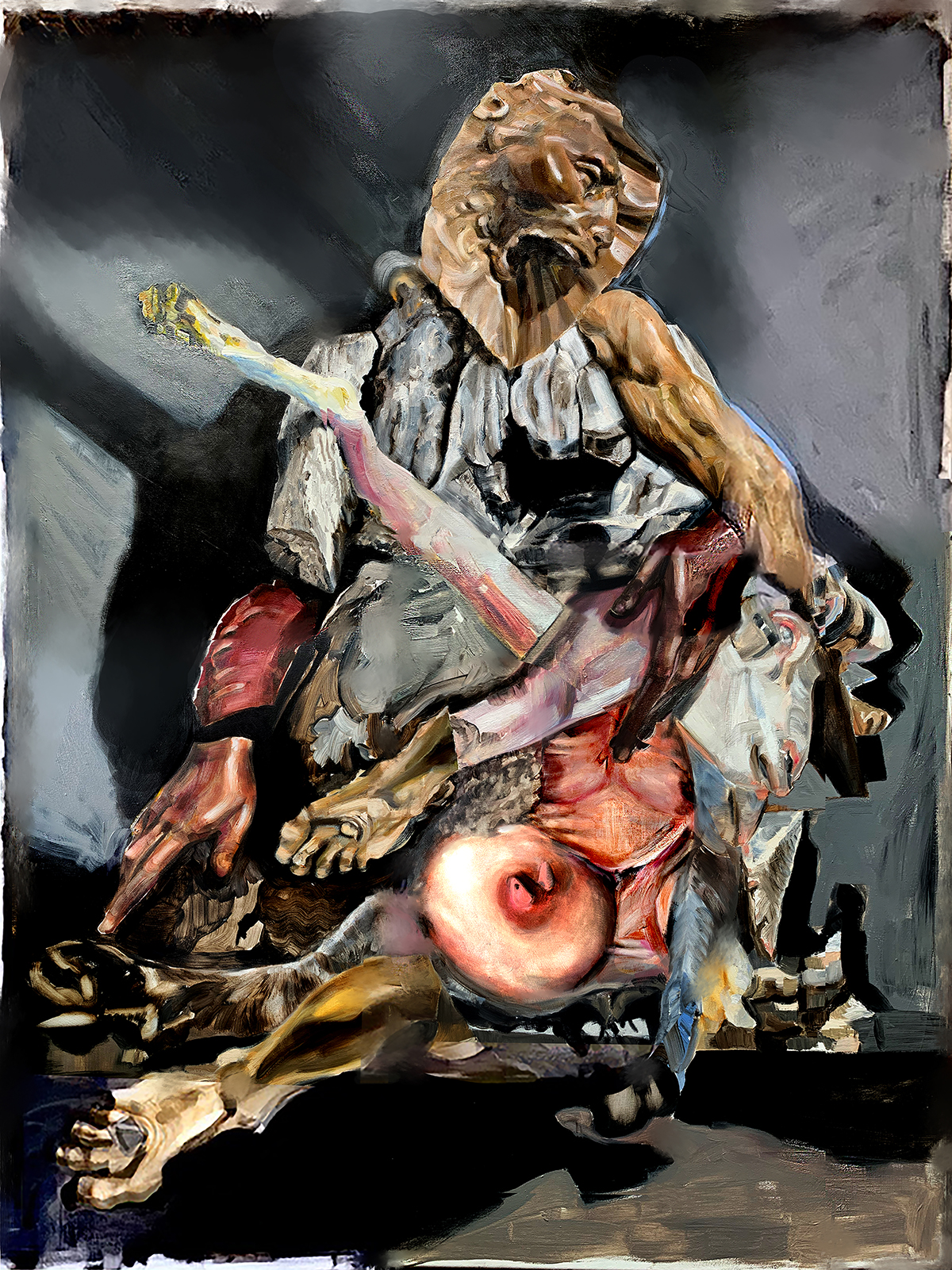

Then I did a second version one with a female figure. It’s called Once Upon a Time: Met HimPike Hoses. The female figure is naked, incredibly skinny, very, very narrow – the way women are supposed to be and not take up much space. Unusually for me, I’ve painted the model very elaborately and hyper-realistically. In that particular picture she’s lying on this very girly kind of 1960s see-through negligée, recalling the heritage of porn star bedroom glamour, that women are heir to.

The title is two fold, the first being the princess in a box, awaiting a man’s kiss so she can flourish – here pushing her toes against the glass ceiling.

Stabat Mater 1 Oil 120 x 160cm on Canvas

The second is referring to the word ’metempsychosis’ the supposed transmigration at death of the soul of a human being or animal into a new body, which the character of Molly uses incorrectly (met him pike hoses) in James Joyces’ Ulysees. I used in the title here, because, not only is Molly a variation of Marian/Mary a.k.a Virgin Mary, but because the same narrative is given to girls since Mary and over centuries, reincarnated over and over – await your prince, don’t take up too much space, don’t leak, sweat or bleed visibly or have body hair, or opinions.

ME: What are your next projects or next areas of exploration?

WKL: A film project. LambEnt. I’m looking at the relationship between ewe and lamb and the sounds they make at a particular moment, again unnoticed and unrecorded, and reworking this as a feminist Stabat Mater.

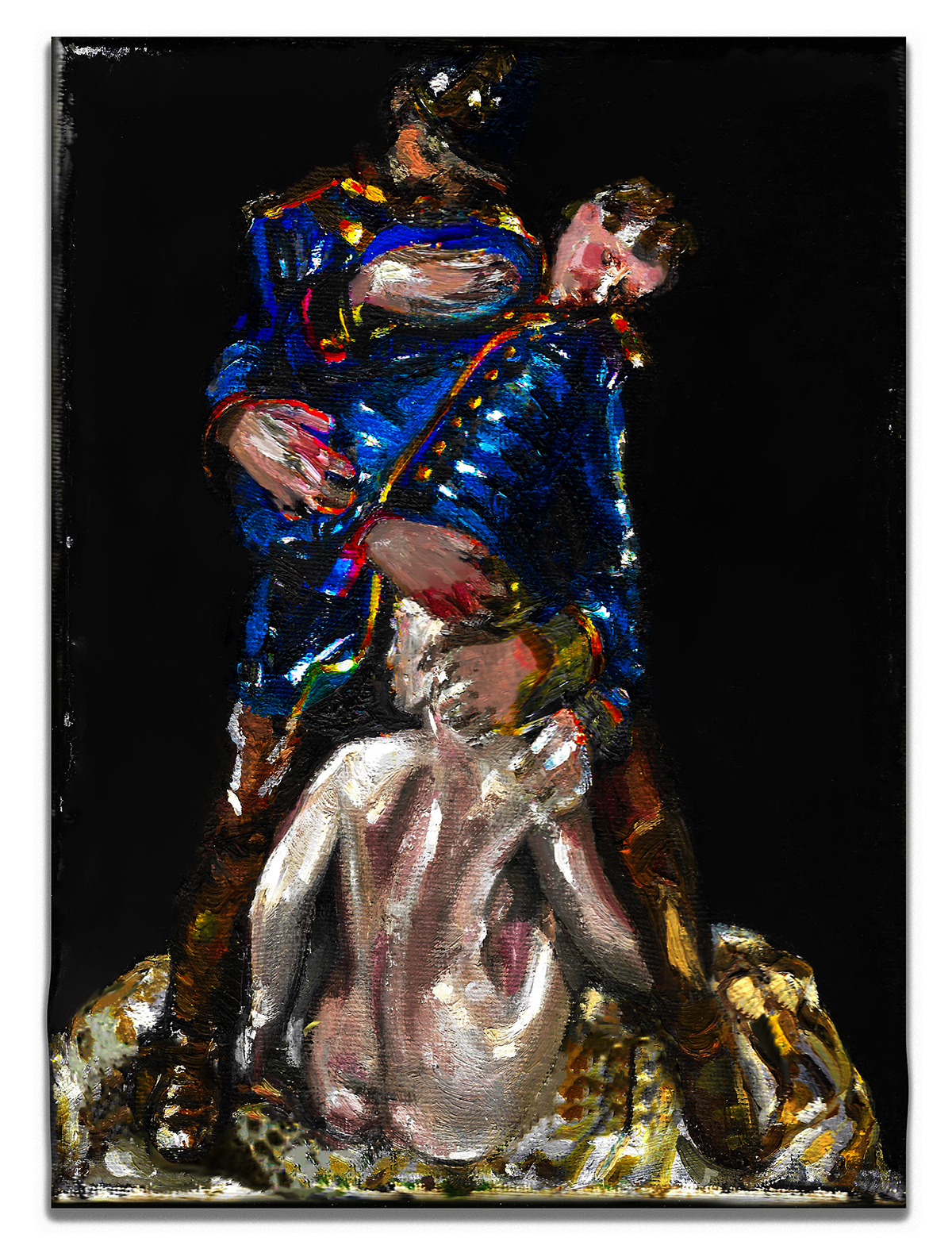

Band of Brothers 18 x 24cm on Canvas

I don’t know if you know much about Catholic music, but there are various parts to a cathedral sung mass, one of which is the Agnus Dei, Lamb of God. Another part of Catholic musical liturgy is a song for Mary called Stabat Mater. In Latin this means ‘standing mother’. That’s what mothers do. They stand and they take it. Stabat Mater is Mary weeping at the foot of the cross, the only occasion where she is vocal. Mary’s relationship with her child is the only intimate experience in her life, like the ewe.

Stick or Twist 60 x 80cm Oil on Board

For the film and music piece I’m making, I am working with actual sheep sound, farmers, animal neuroscientists, with zoomorphic and sacred composers and singers making piece of music to go between the Angus Dei and the Stabat Mater, called LambEnt. It is designed to interrupt the visual and musical canon. It is this voice of nature that is not noticed, not heard, that is the same voice of many that is not heard, particularly currently in Iran but across the world. A global noise. The unheard of all those excluded from the definition of Man is now added to our human species exceptionalism domination of the earth. It is this that has wrought global devastation.

Read more: An Interview with William Kentridge

It’s very exciting and very different for me, doing a collaborative project, because normally I can control what I’m working on. It will be a very short film but if we get it right it will hopefully be very beautiful and powerful and show what art can do. Make the hidden explicit, find the universal in the particular.

Stabat Mater IV 125 x 165cm Oil on Canvas

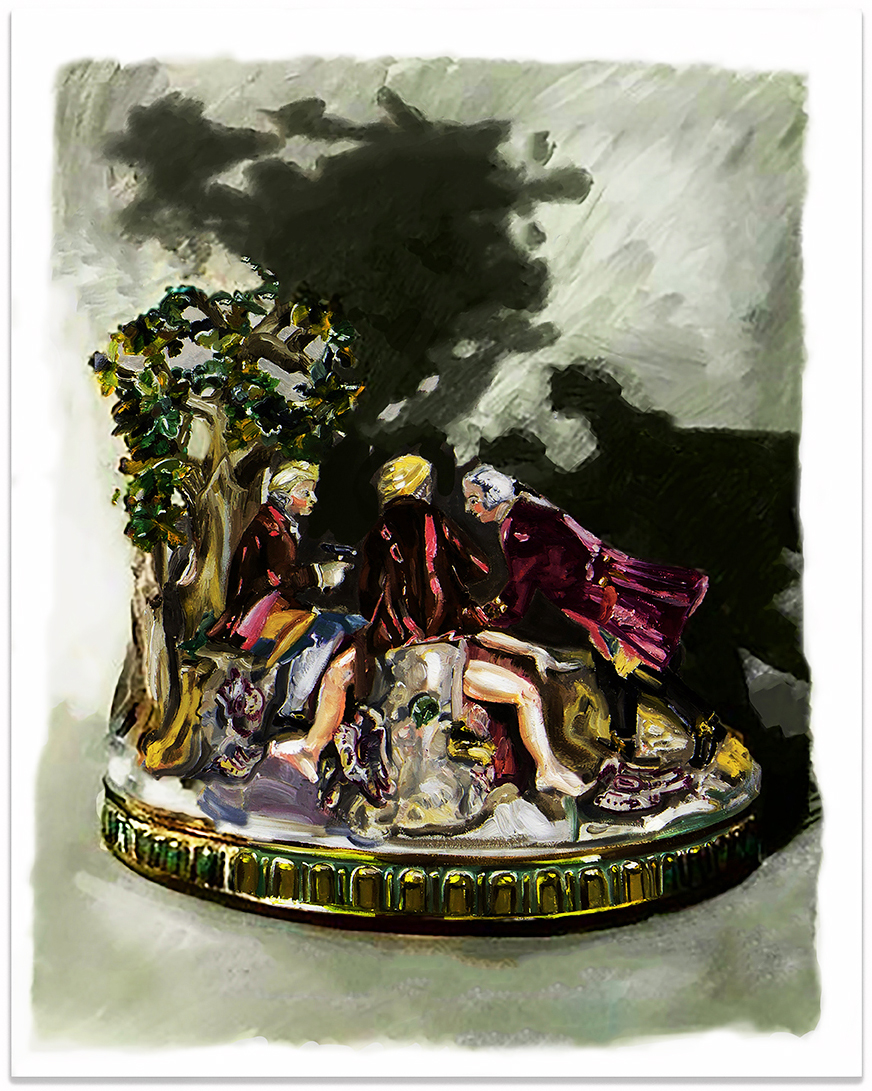

ME: Can you tell me about your porcelain project?

WKL: Absolutely. Historically, those delicate porcelain figurines made by all the famous European companies, Meissen, Sevres and others, were brought out at the dessert course at grand dinner parties. They were designed to show how wealthy you were but also to be diverting and fun, play objects for the rich and jaded.

I’m so interested in these silly scenes that are depicted, at a time when there was such inequality, war, famine and violence. The shepherdesses and card players and cheeky smiling maids and soldiers in these porcelain groups, were existing at a time of rape, poverty, war, violence where even wealthy and well brought up women could be ‘beaten and flung about the room’ by her family, according to Virginia Woolf, for not agreeing to marry the man chosen for her. This one is called Band of Brothers. Rape has always been an instrument of war, but it also occurred casually and often, leaving occupied countries riddled with venereal disease and women who died in shame for being made pregnant. Many terrible things happened to women during wartime.

It’s an ongoing project, it never quite leaves me. I love the fact that you have to look twice to understand what is going on. The paintings are very small and I don’t normally work that size. They are oil sketches really. Again, it’s about collision to create new meanings. Of course, it’s wonderful to paint well and I get very ambitious for these porcelains to look lusciously real, but what they mean matter too. To me, only art can do this. Life’s too short not to care.

W.K. Lyhne’s works are on display at the Zabludowicz Collection in London until 25th June 2023

She is giving a lecture on her work at University of the Arts Inaugural Research Conference on 23rd June 2023, at Granary Square London.

Recent Comments