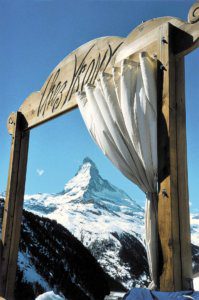

The Matterhorn put Zermatt on the map

DEEP BLUE SKIES, PERFECT TEMPERATURES, NO TEEMING CROWDS, EXCELLENT CUISINE, CLEAN AIR, ENVELOPED BY NATURAL BEAUTY: WHAT’S NOT TO LOVE ABOUT THE SWISS ALPS IN THE SUMMERTIME, ASKS Darius Sanai

Beau Rivage Palace overlooking Lac Leman

The deep midwinter is when residents of the western hemisphere traditionally make their plans for the summer holidays, and the world’s travel industry has long been shaped around these rhythms. Things are changing, as a rapidly increasing number of travellers from countries where ‘summer’ is a far less clearly defined concept (think Singapore, Hong Kong, Brazil, India) make their presence felt. And even among those for whom seasons are clearly demarcated, the tendency towards last-minute travel means booking in July, for July, is more than a temporary trend.

But still: you’ll be reading this in the traditional Western winter, and you won’t have missed the flood of television and magazine advertisements enticing you towards your next grand trip. You may well hear the howling of a winter gale outside, and you might have gritted the drive this morning ahead of the forecast snow.

All of this might go some way to explaining why a quite perfect summer holiday destination for anyone with an active family, a love of luxury, culture, cuisine and the great outdoors, rarely appears at the top of people’s list. Switzerland is associated with many great things, but intense heat and sunshine are not among them, which is a great shame because I and the family picked up the most lasting tan in years during the couple of weeks we spent touring some of this country’s most interesting Alpine destinations last summer. Switzerland may be mountainous, but the southern half of the country is also Mediterranean – it borders Italy, makes wine, serves antipasti and pizza, and some of it even speaks Italian – so sunshine is coupled with clean air and moderate temperatures. The latter is a boon as anyone who has ever tried to take small children to Sicily in August as we did the previous year may know. Forty degrees is OK for sipping rose in the shade, but not for actually doing anything much. In the mountains, strong sun combines with temperatures in the 20s to make for perfect days.

Before I continue, a note: this article has been strung together below from a series of visits at different dates to the destinations below. However, there is no reason at all why someone might not combine some or all of them in one trip, as Switzerland is as compact as it is mountainous.

By The Shores of Leman: The Beau Rivage Palace, Ouchy

Anyone who knows Lac Leman, or Lake Geneva, from its reference in TS Eliot’s rather depressing Wasteland poem might be expecting a rather gloomy place, but arriving in Ouchy, a bijou port village appended to the city of Lausanne, the feeling is just the opposite. The streets – formerly vineyards, which still surround the village – slope steeply down to the lakeside, the pastel coloured buildings speak of Romantic architecture, and the lake itself stretches thick and blue and still, some 10km across to the spectacular mountains on the French side, and as far as the eye can see both left and right. It’s a south facing location, not so much bathed as drowned in delicious southern sunlight: the point at which northern Europe becomes southern Europe. From here, all rivers flow south, to the Mediterranean, and the North European Plain is left behind.

Beau Rivage Palace overlooking Lac Leman

The location deserves a great hotel, and it has one, courtesy of the Belle Epoque travellers who flocked here in search of sunshine and clean air. It pays to be wary of 100 year old palace hotels in Europe, as some of them have fallen into disrepair as travellers take their money away by jet; but I was delighted to see that it was precisely the opposite with the Beau Rivage. The ceilings are high, the corridors palatial and the ballroom is a wonder, but everything has been refurbished to top global standard at what must be an absolutely eyewatering cost to the private owners. Our rooms had two balconies looking out over manicured lawns, a wood, tennis courts, a large outdoor pool and a considerable terrace area – the hotel seemed to stretch in every direction, a great relief after the cramped conditions one encounters even in the very best Mediterranean hotels. The view stretched to the Mont Blanc massif, looming opposite over the lake (Mont Blanc itself is hidden behind its siblings), and to the Upper Rhone valley to the left.

The pool turned out to be two pools, indoor and out, with diversions to tennis, table tennis, giant chess and simply meandering through the grounds as appropriate. The surrounding area is home to one of the world’s highest concentrations of Michelin-starred restaurants, but, frankly, why bother? We started in the hotel’s bar, which has been remodelled with advice from some extremely cool Londonbased consultants in a super-contemporary style that is somehow still in keeping with the location – plenty of greys and dark woods, not too many urban whites. Mojitos, alcoholic and otherwise, provided a good counterpoint to the day’s heat, and I can’t imagine there are many other places in Switzerland where you can get a Mojito as good as at Claridge’s Bar.

Gstaad Palace’s New Lounge

Private spa suite at Gstaad Palace

The oriental-style bar snacks were spot on, but for dinner on our first night we revisited the same spot we had lunch, where I couldn’t resist revisiting a salad of rocket, artichoke, pine nut and parmesan, whose texture still lingers delightfully in the memory. The organic salmon nigiri with yuzu lemon and oyster espuma was a sort of aristocratic sushi that makes one wonder why more Japanese restaurants in Europe are not more adventurous with their nigiri variations. The menu is constantly changing, so you will likely not have what I did, but the conceptualising and cooking were pinpoint sharp. As was the wine list: a Crozes Hermitage from Jaboulet, from the excellent 2009 vintage, accompanied beautifully (although I was later to regret not having tried one of the excellent selection of Swiss wines).

The Cafe Beau Rivage is somewhere you could eat every meal of every day, but the hotel also owns a highly popular Italian trattoria/pizzeria in the neighbouring building whose terrace is the meeting point of the young cool set of the area, and a highly regarded traditional Japanese restaurant, Miyako, in the main building.

We left feeling rather guilty that we hadn’t indulged in a private boat trip on the lake, or visits to neighbouring vineyards, but it is always best to leave something for next time. The Beau Rivage palace is that rare example of a contemporary classic that makes its destination what it is: without it, Ouchy (pronounced Ooshy) would be a pretty lakeside village like many others in Switzerland and Italy (and it does have an Italianate feel).

Gstaad and the Palace

Ouchy may have views of high mountains, but in Swiss terms it is a lowland destination, on a large lake at a mere 375 metres altitude. From now, our trip would take us ever higher into the Alps. A little way down the lake from Lausanne is the town of Montreux, known for its globally-celebrated jazz festival but a slightly humdrum place otherwise. Montreux’s railway station is the starting point of the Goldenpass, one of the Alps’ most famed train rides. The train, with a special panoramic viewing roof, makes its way not along the lake, like the main train line, but up the mountainside abutting the lake. It climbs quickly to 1000 metres, over a pass, and then descends gently into a wonderland of deep green Alpine meadow, woodland, lush valleys, streams, and chalets. The children kept a lookout for Heidi, and I kept wondering if it was all a projection by the Switzerland Tourism, the sophisticated national tourist authority, but no: it was real. The air was cooler but still warm, the sunlight tempered by dark forest, the slopes rising to snow patches below rocky peaks.

Train arriving in Gstaad from Montreux

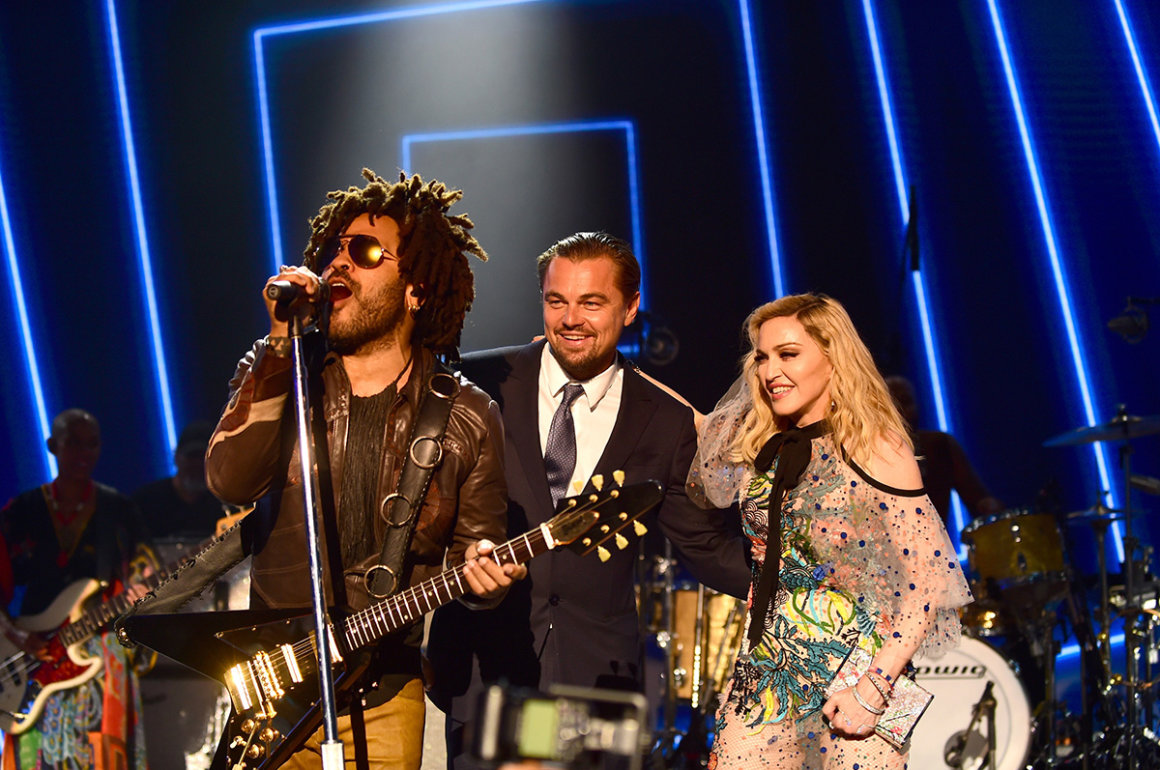

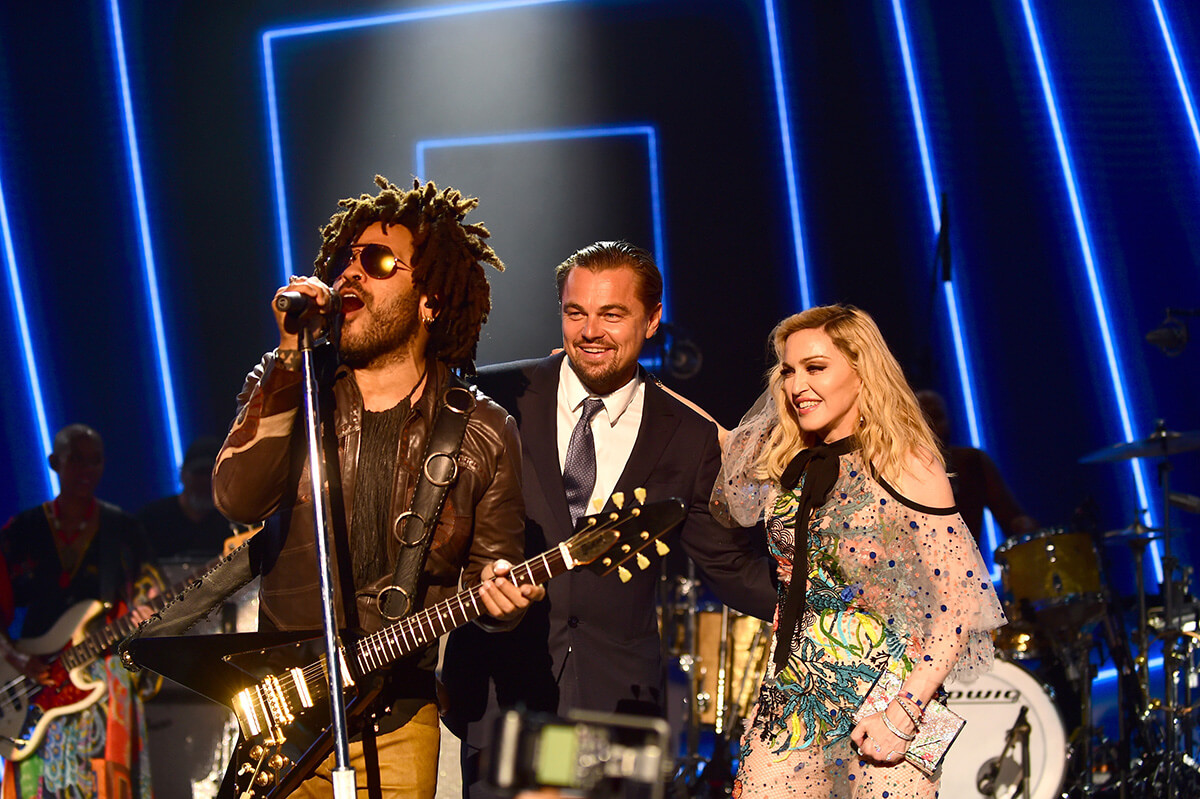

Gstaad is at the end of this expanse of Alpine perfection, a little town in a bowl of big hills and small mountains, with an open view in every direction. And the Palace in Gstaad sits atop the town like a fairytale castle, with its own tennis courts, spa hewn into the rock, and permanent residence (or so it seems) of clients who have either just arrived or are just about to leave in their private jets from the nearby airstrip. The rockfaces of the mountains turn gold in the dusk sunlight as the conversations on the terrace turn to what the next generation will do with the wealth amassed by this one. Not having to worry unduly about such things, we sipped our aperitifs every evening and spent daytimes split between the hotel’s own spa and exploring the mountains.

The spa feels very Swiss, hewn out of the rockface under the hotel, with a granite-lined pool that stretches in an Lshape to a glass wall that opens fully on summer days. The treatments are perfectly thorough and correct as you would expect, my massage unclicking a joint that had been frozen for months; and the adults-only hydrotherapy pools are a fine place to spend a while amid the view. It was here that I noted another key advantage over traditional summer destinations: you are not overwhelmed by other people’s children; in fact, they are a mere footnote to the rather discerning adult clientele. The Palace is a lively place in winter with its louche nightclub Greengo, but in summer it is altogether more chilled out.

Gstaad’s mountains are not toweringly high by Swiss standards, but it’s an excellent place to start: we took a lift up to a restaurant atop one of the mid-size mountains from where the view stretched to the next range behind, and after a rustic lunch of veal (adults) and veal sausages (children) the offspring spent an enjoyable hour or two amusing themselves by seeing if there was anything in the meadow the restaurant owner’s pet goats would not eat. Branches, dandelions, weeds and wildflowers alike were consumed by the goats-with-a-view.

The people, like the goats, traditionally ate what was available locally here, which explains the surfeit of excellent veal which, being local, comes with fewer animal rights worries. And then there are the products, notably the local Gstaad cheese and the considerably more famous Gruyere from just down the valley. These combine most notably in a fondue, and on the recommendation of the local tourist office one evening we took a twenty-minute journey to Gsteig, the next village in the valley, for a fondue at Baren Gsteig. Amid low beams and cowbells, we settled down to the freshest fondue I have experienced. It may sound odd to call a cheese fondue fresh, but I suspect the fact that all the cheese used

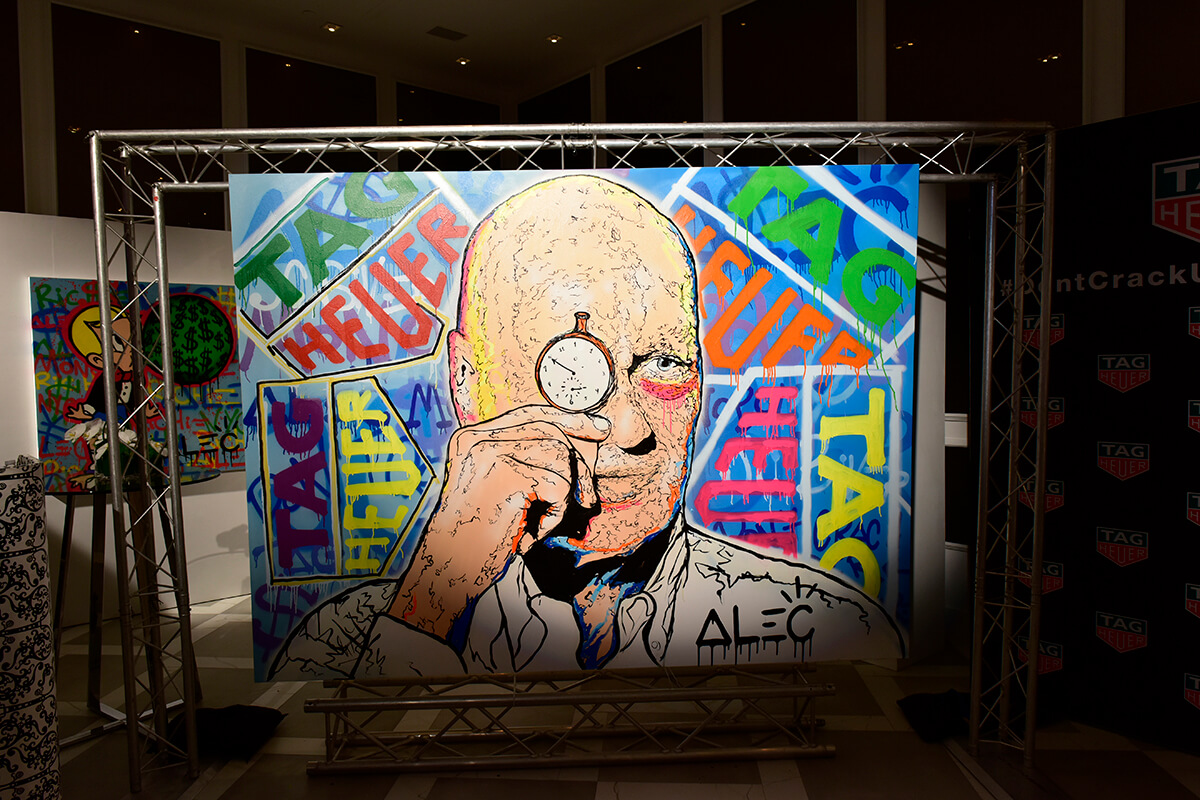

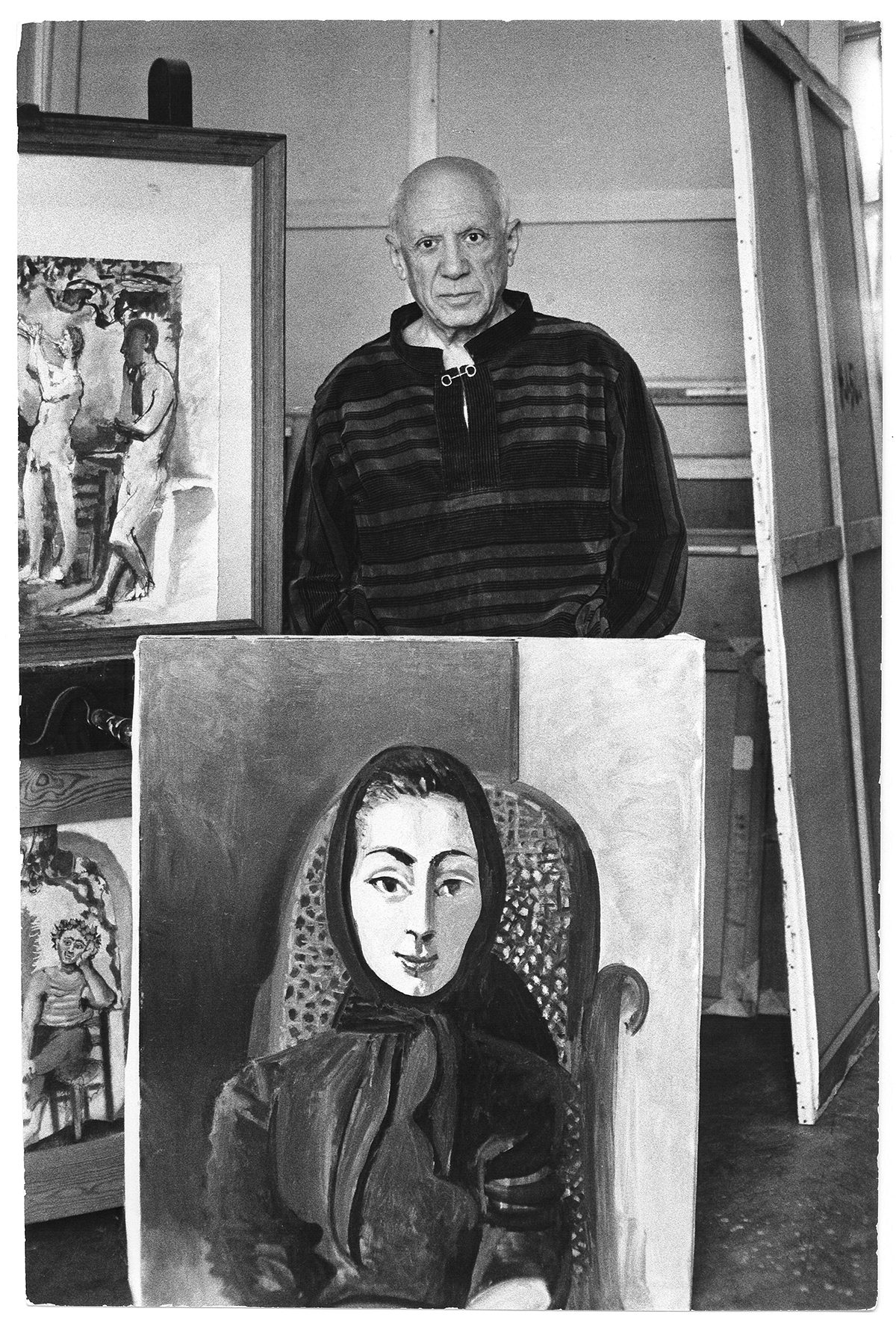

Edward Whymper was the first to climb the Matterhorn

was unpasteurised hard cheese made a significant difference to both the bite and the minerality of the dish. The bread was just right too, slightly stale (one day old, we were told) crusty local sourdough – if it’s too fresh, it flops into the melted cheese. The fondue also contained a dose of the local brandy, adding more bite and fruit freshness.

Another evening we went to the oldest restaurant in Gstaad proper, at the Hotel Post, on the bijou little high street, where the steak (local, again) had a combination of metallic earthiness and butter-tenderness I haven’t encountered elsewhere.

The Palace is a most civilised place to return after such rustic outings: the lobby and bar have a chalet-like feel, but the view is all around. On our last evening, the moon lit up the glacier at the side of the far peak up the valley. We were due to visit the glacier, accessible by cable car, but this was not to be this time. Again, something for another time.

To Zermatt

If there is one place in Switzerland, or indeed the Alps, that can claim to be as important in summer as it is in winter, it is Zermatt. Skiers may know the resort for its challenging black runs, excellent apres-ski, and cosy haute-cuisine mountain dining. But Zermatt is that rare resort, where visitors and global celebrity predated going down mountains with two planks tied to your feet. Like many chi-chi Alpine villages, it was for centuries a remote and impoverished farming hamlet, but its transformation came in the 19th century when Victorian-era Britons, bent on surmounting every challenge the world held, came to conquer its iconic mountain, the Matterhorn.

In the 1860s, successive climbing parties arrived in Zermatt bent on scaling the Matterhorn (now known to anyone who eats chocolates or buys Caran d’Ache pencils) and other peaks in the amphitheatre that surrounds the valley: along with Chamonix, the French

village at the foot of Mont Blanc, Zermatt can lay claim to being the home of Alpinism, of mountaineering as we know it.

Even 150 years later, with the arrival of the big-money skiing parties and the accessibility of higher and more challenging mountain ranges in Asia and South America, Zermatt still attracts the Alpinists in summer. The Matterhorn’s most accessible ridge, first climbed by the Englishman Edward Whymper in 1865 in a tragic expedition that involved the death of four of its members and which cemented the mountain’s ominous reputation, is now more accessible. With the help of fixed ropes, a carefully mapped route, and modern equipment,

hundreds of people climb it every year. But its other aspects, and in particular its vertical North Face, remain a monumental challenge, as do a number of the 30 other 4000 metre high peaks that surround Zermatt. Oddly, none of these other peaks, the largest collection of 4000 metre mountains in the Alps, are available as the train ascends the valley to Zermatt.

The village still bans cars, so train is the only way to arrive. Alight at the train station, in a mini urban sprawl, and you may wonder what the fuss is all about. But take a few paces over towards the river, look up, and there is the Matterhorn, as otherworldly as it ever was, rising to 4478 metres above Switzerland and Italy.

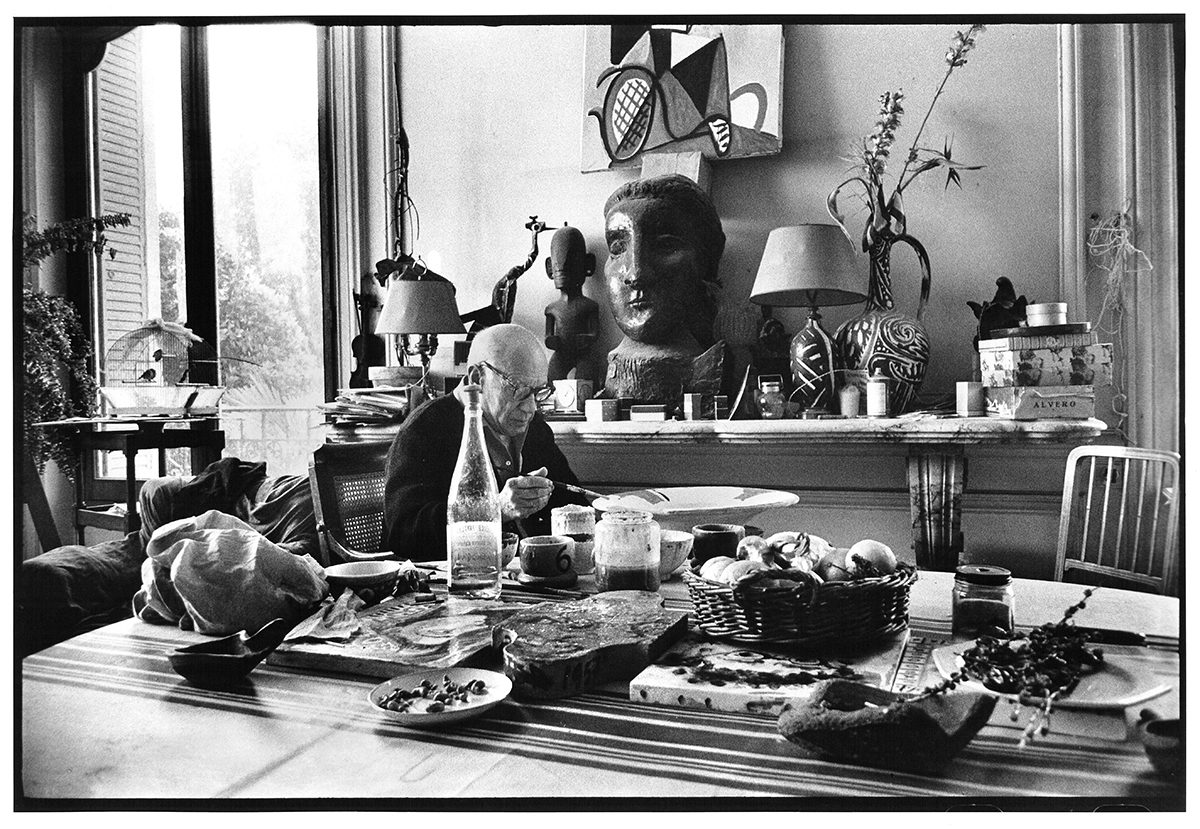

For me there was only one place to stay in Zermatt. The Monte Rosa hotel is the village’s original hotel, built in the 19th century to house those climbing parties, and gently renovated since. Its heart and soul are in Alpinism: the walls are festooned with souvenirs from climbing parties, letters of good wishes from the likes of Winston Churchill to resident climbers, some of them triumphant, some doomed.

The bar is cosy, low-ceilinged, a place to exchange stories about the day’s adventures, although today’s climbers are no longer all gentlemen of the aristocracy and many of them stay in the town’s youth hostel instead. The restaurant is a classic white tablecloth hotel dining room where you dine on the set menu and choose from the array of Swiss wines on the list, including some very interesting Pinot Noirs from the east of the country, and, my personal favourites, some rich, spicy satisfying single vineyard wines made with the local Cornalin grape in the sunny Swiss Rhone valley nearby.

Monte Rosa, the home of Alpinism

The Monte Rosa still occupies its original site in the very heart of the village on the square, and the hotel itself attracts carefully limited numbers of tourists come to visit the original home of the Alpinists. Its sister hotel, the Mont Cervin, a couple of hundred metres away, has a large pool, spa and garden that guests can use. The view from our suite was directly to the Matterhorn’s north face, with the village church beside us. And Zermatt, you rapidly learn when you arrive there, is not about lounging about in your hotel: it is about activity. There is a cog railway station opposite the main railway station in the village, and here we boarded a narrow gauge train that inched its way through the village and up through the thick forest on the steep valley sides. So far, Zermatt had remained an enigma, the Matterhorn towering over it, but the vast amphitheatre of mountains that accompany it remaining hidden behind the steep valley sides.

As the Gornergrat train climbed, peaks started to reveal themselves on the opposite side of the valley. Like an animal revealing its sharp teeth, they emerged, pyramidal rock faces rising above the glacier and pricking the sky, and within minutes we were faced with a panorama of jagged edged 4000 metre mountains, from the Weisshorn to Dent Blanche, that climbers the world over come to conquer.

The train’s track rose above the treeline and still we carried on climbing. Another towering series of jagged peaks emerged on our side of the valley, plunging down into scree, valley, and forest. The Gornergrat mountain we were ascending flattened out, the train climbed over a ridge, and suddenly the most spectacular view of all confronted us, a huge series of snowy giants looming at us from directly across the long tongue of a glacier. This was the Monte Rosa, the highest mountain in Switzerland, and its associated peaks.

Emerging, blinking, onto the rock and summer snow patches of Gornergrat, 3100 metres up, we climbed to a rocky viewing point. There was a 360 degree view of peaks higher than 4000 metres, and very little sign of human civilisation. Below us on one side a near vertical slope dropped to the glacier, where we could just pick out the figures of some climbers tramping their way back from an expedition.

Walking down a little from Gornergrat, trying not to get vertigo, we passed a heavenly mountain lake, surrounded on all sides by wild flowers, in which a rockpool of tadpoles swam, and where an elegant green frog sat sunning itself on a grass patch. The path picked its way through more high meadows of wildflowers, around the ridge, and to the Riffelberg train stop, where we boarded the train home.

On another day we took a lift up the neighbouring mountain, past a little green lake, and strolled down to Findeln, a little hamlet in a sainted position facing the Matterhorn across the valley. We sat on the terrace at the Findlerhof restaurant and enjoyed astonishing food: sashimi with a lime dip; beautifully cooked sea bass; veal in a gentle white wine sauce. The terrace was spacious, wooden and rustic with an astonishing view; the food was perfect urban sophistication. Apparently there are dozens of restaurants like that on Zermatt’s mountains, something the original climbing parties plainly missed.

Pontresina and the Engadine

There is a train that connects Switzerland’s two most famous resorts, Zermatt and St Moritz, directly. The Glacier Express runs several times a day in summer, and while it neither goes through a glacier (although you see plenty) or goes very fast (rather the opposite), the seven hour journey was a great way to kick back, relax and watch central Switzerland proceed slowly past.

Our destination was not St Moritz itself but its chic neighbouring resort of Pontresina, and its flagship hotel, the Kronenhof. Pontresina is a tiny Italian-feeling village on a ledge above the high Engadine valley that cuts through the mountains of eastern Switzerland, near the Austrian and Italian borders. The Kronenhof has a grand courtyard on the village’s main street and a dramatic view across the valley and up towards the glaciers of the Piz Buin.

It was remarkable and rather wonderful to find a hotel of such sophistication so deep in the mountains. The huge indoor pool has been built onto the valley side of the hotel and, surrounded by glass, gives a feeling of flying, with mountains all around. Our suite’s balcony looked down onto forest and up onto glacier, and the jazz bar, again with dramatic views, felt very F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Pontresina’s flagship hotel, the Kronenhof

The Kronenhof is a big hotel with a panoply of distractions, including one of the region’s finest restaurants (which we have saved for next time), an extremely spacious and throrough kids club, replete with a proper children’s library, and a spa, attached to the pool, so good that it attracts the glitterati from nearby St Moritz all winter. Our room was decked in contemporary Alpine cool, plenty of blond wood, stone and grey, with generous panorama areas to look at the views, and a bathroom squarely aimed at the demanding international traveller.

One morning, leaving the hotel, we took the quaint, twoseater chairlift up through the forest to Alp Languard, a restaurant on a ridge overlooking Pontresina’s valley and the Engadine; another high mountain lunch of extraordinary quality ensued, and a hike up towards the high ridge at the top, which, eventually, defeated us. We took the chairlift down through the forest, amid the scent of pine and wildflowers. Tea at the Kronenhof involved the magnificent sight of the mountains turning rose, as the sky at this high altitude (the village is at 1800m) turned pink then midnight blue.

Perhaps the most memorable aspect of our stay was the evening we made our way down the 10 minute walk to the bottom of the valley, to be met by a coach and two – two horses pulling an open carriage. The children were thrilled, and the horses made their way up the secret Val Roseg. It is secret because it is a nature reserve, with no cars or even mountain bikes allowed – only horses and hikers. At the end of the high valley loomed a great white dome of a mountain, above the Roseg Glacier, and it was to the edge of this glacier that we made our way, up the enchanted valley, along a river, past a family of marmots, the most elusive of Alpine creatures, who stood to attention as we rode past.

Dinner was at Alp Roseg, another spectacular mountain restaurant with a vast wine list and haute-rustic cuisine, where steak in cafe de paris sauce was consumed with so much gusto you might have thought we, and not the horses, had done the climbing. The journey back in the starlight was equally memorable.

The Waldhaus at Flims

Flims is a resort that has become something of a legend among the snowboarding community. It sits on a very sunny, south facing shelf above the Rhine valley, in eastern Switzerland, halfway between Pontresina and Zurich. On the forested plateau adjoining Flims, in its own generous grounds, sits the Waldhaus resort, a Victorian-era grand hotel that has been developed and brought up to date. The grounds are generous enough to incorporate forest, copious lawns, an adventure playground, and a large petting zoo where the children spent amounts of time befriending donkeys, goats and chickens – the animals were so well fed by the hotel that their attempts to feed them usually ended in failure.

The Waldhaus resort in Flims

The hotel has a glass-encased indoor pool and interconnected outdoor pool, and, next to it, a natural swimming pool where you can swim in non-chlorinated water among frogs and small fish.

We enjoyed a memorable cocktail and canapes on the terrace of the pavillion one evening as the sun set over the mountains opposite, and a very sophisticated meal at one of the hotel’s fine dining restaurants, Rotonde, with its floor to ceiling windows looking onto the forest; those in search of even higher cuisine can venture to Epoca, which has 17 Gault Millau points.

A trip on a chairlift took us to the Berghaus Naraus, a restaurant on a south-facing ledge with sweeping views and an excellent line in barley soup and air-dried beef – and yet another quite astonishing wine list, which we resisted, it being lunchtime. Instead

we saved ourselves for dinner at the Arena Kitchen Flims, a cool, urban bar,

club and restaurant that could have been in Vermont or Colorado, in the city centre. It was quiet in summer, but you could imagine the teeming hordes in the ski season.

And that, I think, is the way I like it: clean sunshine, pure air, astonishing views, focussed cuisine, excellent service, Europe’s best hotels, and no teeming hordes. I’ll be back to Switzerland in summer.

Beau Rivage Palace: brp.ch

Gstaad Palace: palace.ch

Monte Rosa: monterosazermatt.ch

Grand Hotel Kronenhof: kronenhof.com

Waldhaus Flims: waldhaus-flims.ch

The best way to travel around Switzerland is by train. See swissrailways.com for details

Clinique La Prairie has established itself as a leading name in longevity research, offering wellness programmes for over ninety years. For its inaugural escape far away from its traditional Alps and Lake Geneva landscape, the brand has set base on North Island Resort in the Seychelles to create a complete Clinique La Prairie experience

Clinique La Prairie has established itself as a leading name in longevity research, offering wellness programmes for over ninety years. For its inaugural escape far away from its traditional Alps and Lake Geneva landscape, the brand has set base on North Island Resort in the Seychelles to create a complete Clinique La Prairie experience

JOHAN GRANVIK

JOHAN GRANVIK

KAREN O’MAHONY

KAREN O’MAHONY

In 2020, the building of two new residential properties will commence for those who are looking to own in

In 2020, the building of two new residential properties will commence for those who are looking to own in

While many of the top one per cent choose to base themselves in traditional ski-in, ski-out

While many of the top one per cent choose to base themselves in traditional ski-in, ski-out