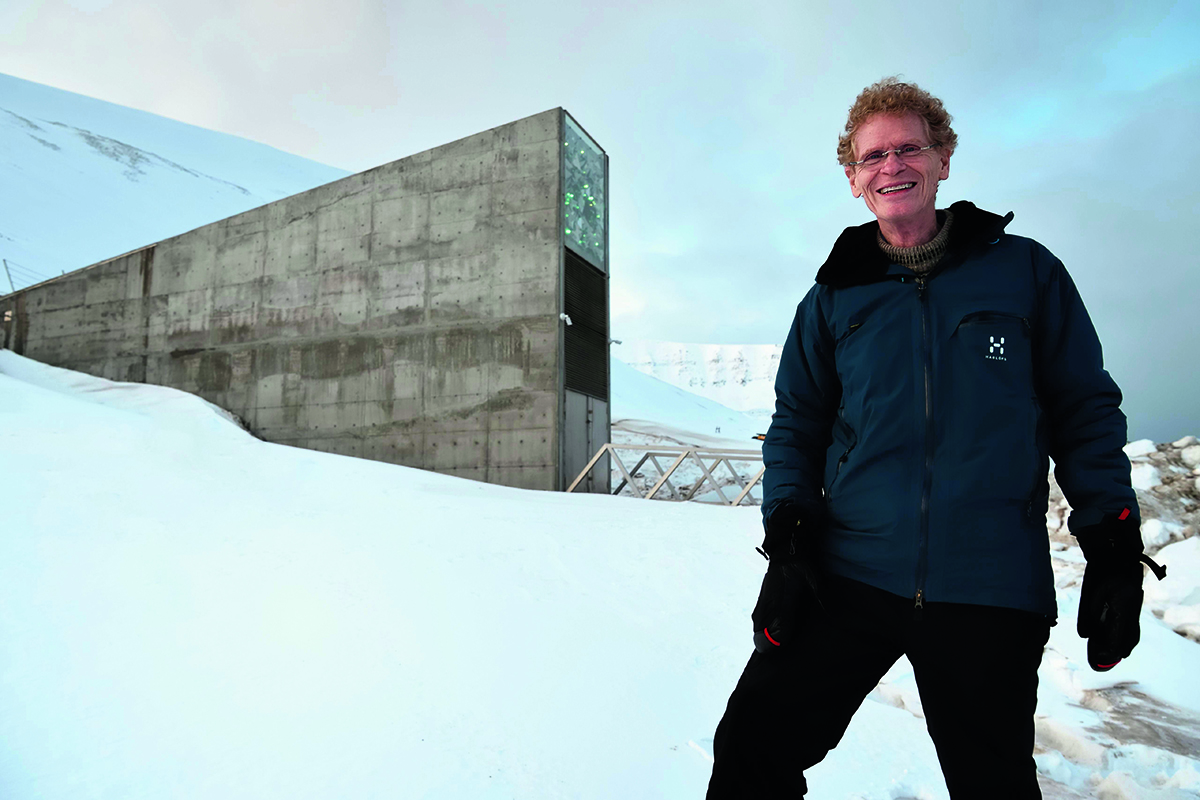

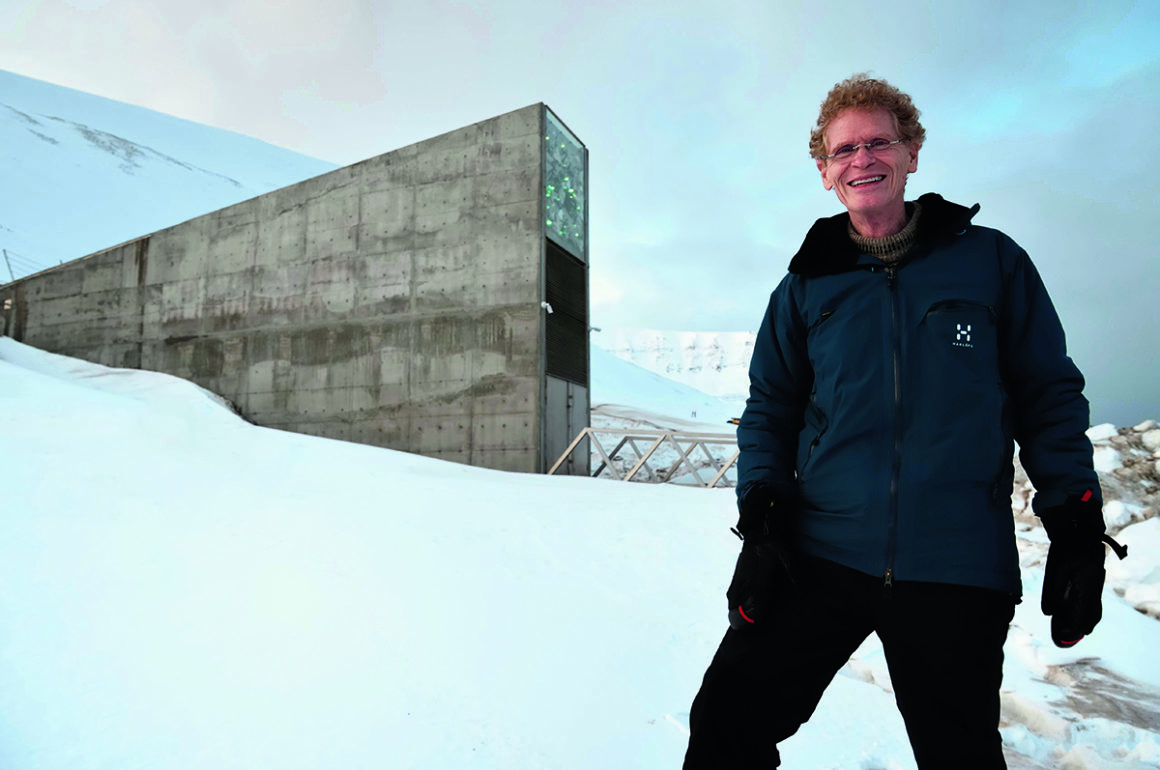

Cary Fowler outside the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Hemis/Alamy

Cary Fowler is the American visionary who established the Svalbard Global Seed Vault to ensure the security of all our crop seeds come war, famine or plague. Such future-proofing is ever more important, he tells Andrew Saunders

Appearances can be deceptive. The modest steel and concrete protrusion jutting out from the side of a mountain on the remote Norwegian Svalbard archipelago may not look like much, but it’s actually the entrance to one of the most valuable facilities on earth. Within the vaults behind it, tunnelled 120m into the rock and isolated by layers of both physical and biosecure protection to prevent contamination from the outside world, lies neither gold, gems nor fine art but something much more precious – a collection of seeds of the world’s food crops that we all rely on for our daily nourishment.

It’s the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, and it was built to help protect the world from the growing threat of biodiversity loss, particularly arising from climate change. Loss of biodiversity may not be as well-known as other risks associated with global warming such as higher temperatures and rising sea levels, but it is at least as important, says Cary Fowler, biodiversity specialist and a member of the team that co-founded the vault in 2008. Because, he asks, where would we be without food to eat?

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

“We are in the midst of the greatest and quickest change in climate in the history of agriculture, and our future food security is totally dependent on biodiversity. How likely is it that all the varieties of all the food crops we rely on will be able to adapt and continue to grow in conditions that they as species have never experienced before? We need to preserve diversity so that we can help our crops adapt to these new conditions.”

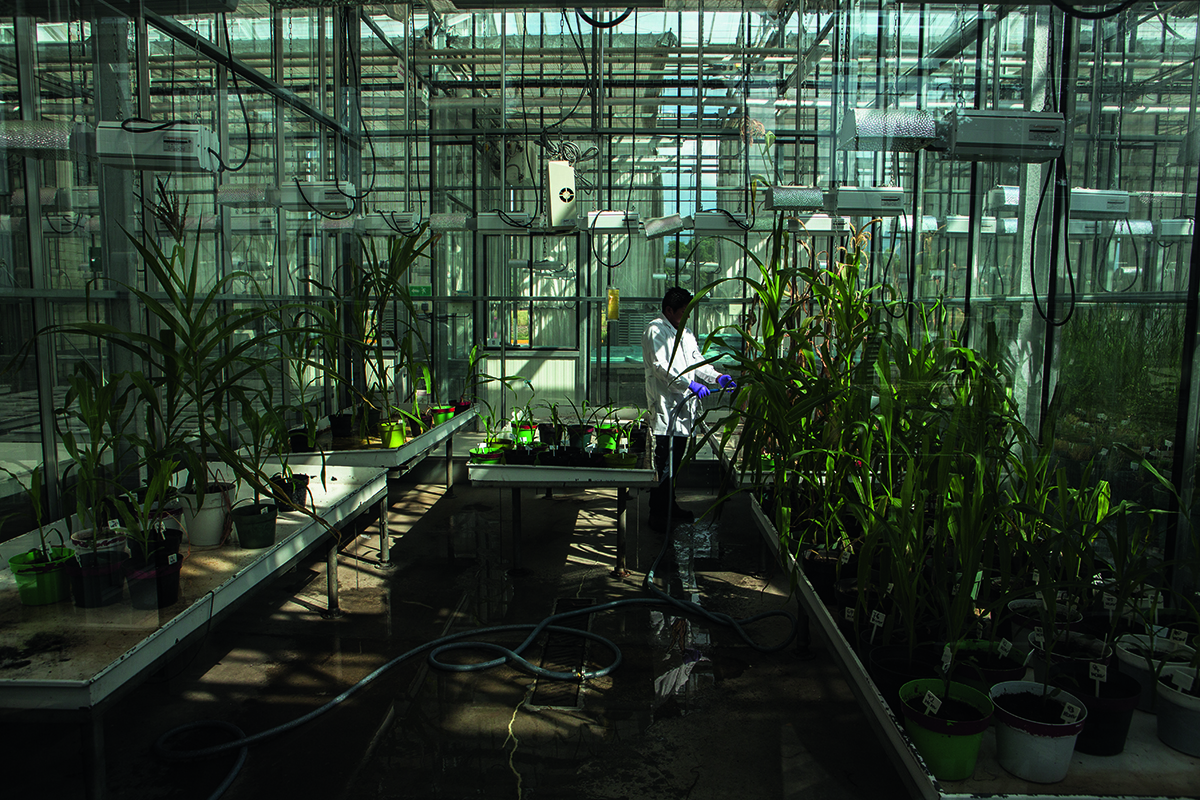

But how exactly does keeping a collection that so far comprises 1.1 million seed samples (with each sample containing an average of 500 seeds) from more than 230 countries literally on ice at 78 degrees north help manage climate change? As Fowler explains, different varieties of rice, wheat, millet and so forth have specific traits that suit them for specific environments. Short-stemmed cereals are less susceptible to damage from wind and rain, for example, while others may be more tolerant of heat or drought. Samples of plants with those types of traits are a crucial hedge against the uncertainty of the future. The research done by bodies such as the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in Mexico is critical in our understanding of which varieties are resilient to changing environments.

The entrance to the seed vault.

“Climate change will advantage some crops and disadvantage others,” he says. “If I had a time machine and could go forward 100 years, I am confident that some of the important crops we grow now will have become much less important, and others will have come to the fore. The seed vault collection makes that kind of adaptation possible.”

So, Svalbard is really a kind of global insurance policy, a backup resource to help maintain food production and preserve lives, societies and economies in the event of any natural or human-made disaster, including, but not limited to, climate change. Many of the varieties it contains are no longer grown because they have been replaced by new varieties that are more productive or easier to cultivate, but preserving them is no less important from a biodiversity point of view. “You might have a sample of wheat, say, that by modern standards is just terrible, but it could have one vital trait that is not found anywhere else – resistance to a disease that we don’t even know about today, for example. We can then crossbreed it to get that trait into the modern variety,” explains Fowler.

Read more: Markus Müller on the Importance of Global Sustainability Standards

The Seed Vault was set up as a partnership between the Norwegian government, the Nordic Genetic Resource Centre (NordGen) and the Crop Trust (of which Fowler was previously executive director and where he is now a senior adviser) to conserve crop diversity in perpetuity. He well remembers the scale of the task that faced him and the team he was leading in the early days. “I’d been in the field for a few decades and I knew what was necessary to conserve crop diversity, but to do it in perpetuity? That was an interesting challenge. There are not too many jobs on the planet that involve doing something in perpetuity.”

One of the tunnels inside the vault

The vault’s construction and location were carefully chosen with that longevity in mind. Carved into the Arctic mountain, it is both physically secure – it could withstand a substantial bomb blast – and naturally cold and dry, the ideal conditions for preserving seeds. The ambient temperature inside the vault is approximately -4˚C, and mechanical cooling pulls that down to the optimum storage temperature of -18˚C. But even if the cooling system should fail, the collection would remain safely preserved for several decades. “There would be plenty of time to get up there and fix the equipment. There are no guarantees in this world, but we did the best we could with it.”

The hardest work, however, lay elsewhere, he says. “The management structure – that was the real challenge. I wanted a facility that involved as few human beings as possible, and that more or less ran itself. So that’s what there is – there are no staff located on site and the facility is naturally frozen.”

Read more: Dimitri Zenghelis on Investing in the Green Transition

Former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has called the Seed Vault an “inspirational symbol of peace and food security for the whole of humanity”, and there is a strong social justice element to its role. “I am very aware that when we do have a world food crisis, it will be the poorest of the poor who are the first to suffer,” says Fowler. “I grew up in the time of the civil rights movement in the US and have a strong interest in social justice as well as agriculture. My home is in Memphis, Tennessee, where Martin Luther King was assassinated on 4 April 1968. I was at his last speech the night before he was killed; it was very emotional.”

The next job for the Svalbard team – and for Fowler himself – is to raise the profile of biodiversity, both with the public in general and with philanthropists in particular. “Biodiversity is the greatest world problem that we face that we can actually resolve. If I ask you ‘What’s your solution for climate change?’, that’s really big and complicated. But we do have an answer to the question of how to preserve the biodiversity of food production – we know how to do that.”

What’s required is greater awareness and a willingness for institutions and wealthy individuals to recognise the importance of funding biodiversity, he adds. “If I was a wealthy individual and I wanted, for example, to save the whales forever, that would be a great thing to do but how much would it cost and how would you go about doing it? There’s no organisation in the world which could tell you that.”

Maize plants in a greenhouse at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, Mexico. Photo courtesy of The Global Crop Diversity Trust. Juan Arredondo/Reportage by Getty Images for The Global Crop Diversity Trust

By contrast, saving crop diversity is both practical and relatively affordable. Smaller crops could be saved for around $5m, Fowler calculates, and the cost of preserving even the most important global crops is less than you might expect. “I can tell you the answer for rice, which is our biggest crop with the most samples and therefore the most expensive. Somewhere between $35m and $50m in an endowment fund would generate enough income to save all the rice diversity in perpetuity.”

In short, his pitch is that food is the bedrock of human existence, and crop biodiversity is a great way to maximise food security in a time when climate change and a host of other potential calamities are threatening it. “Those sums are well within the scope of a number of wealthy people, and they would be the first to do something quite extraordinary and inspiring. Can you name any other major world problem that we have solved, reliably and forever, within the lifetime of someone living today? Well, we can do it with this one.”

Additional research by Candice Tucker

Find out more: caryfowler.com; seedvault.no

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2021 issue.

Recent Comments