Maurizio Cattelan

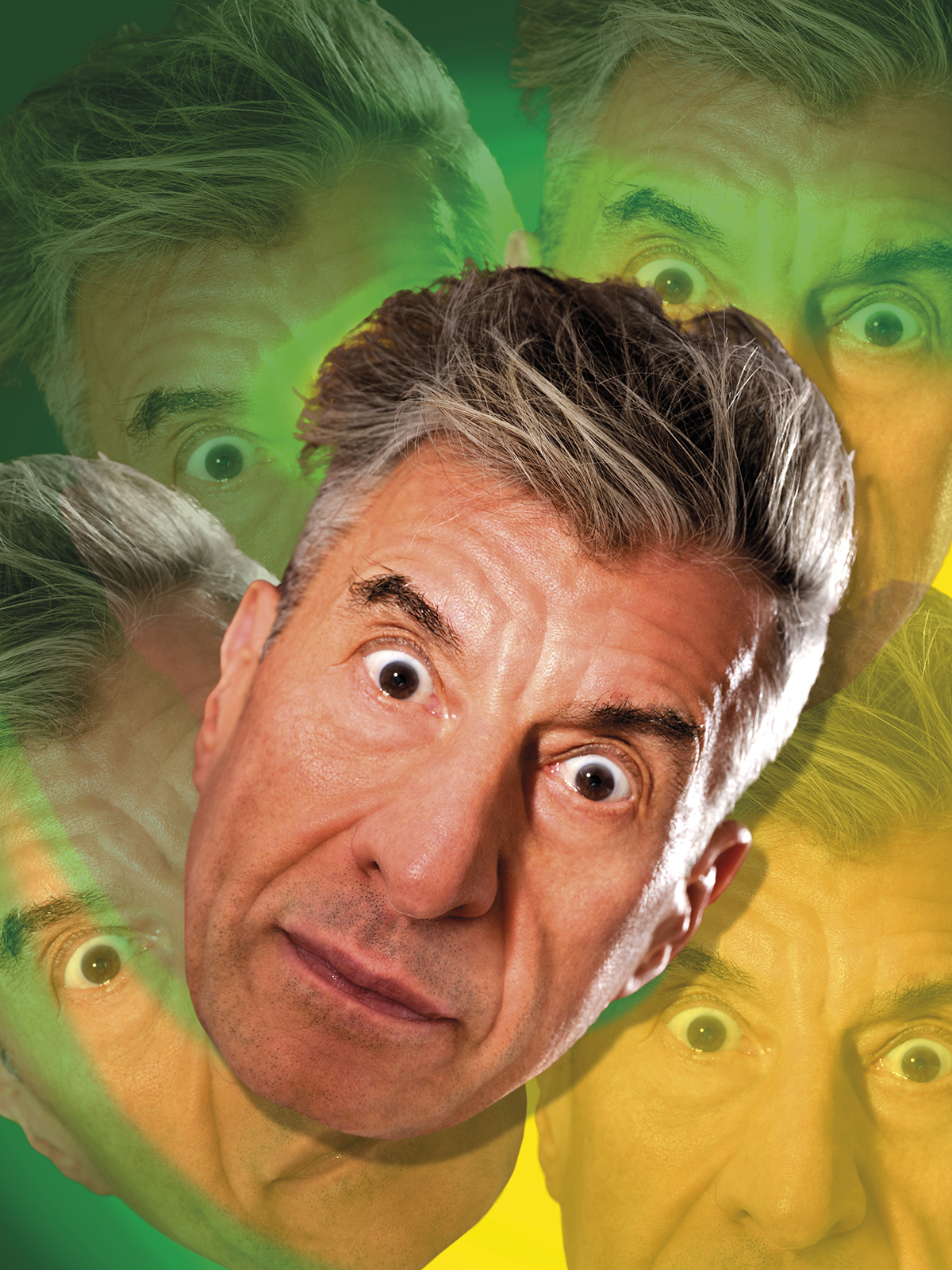

self-portrait created by the artist and Pierpaolo Ferrari for LUX

Maurizio Cattelan

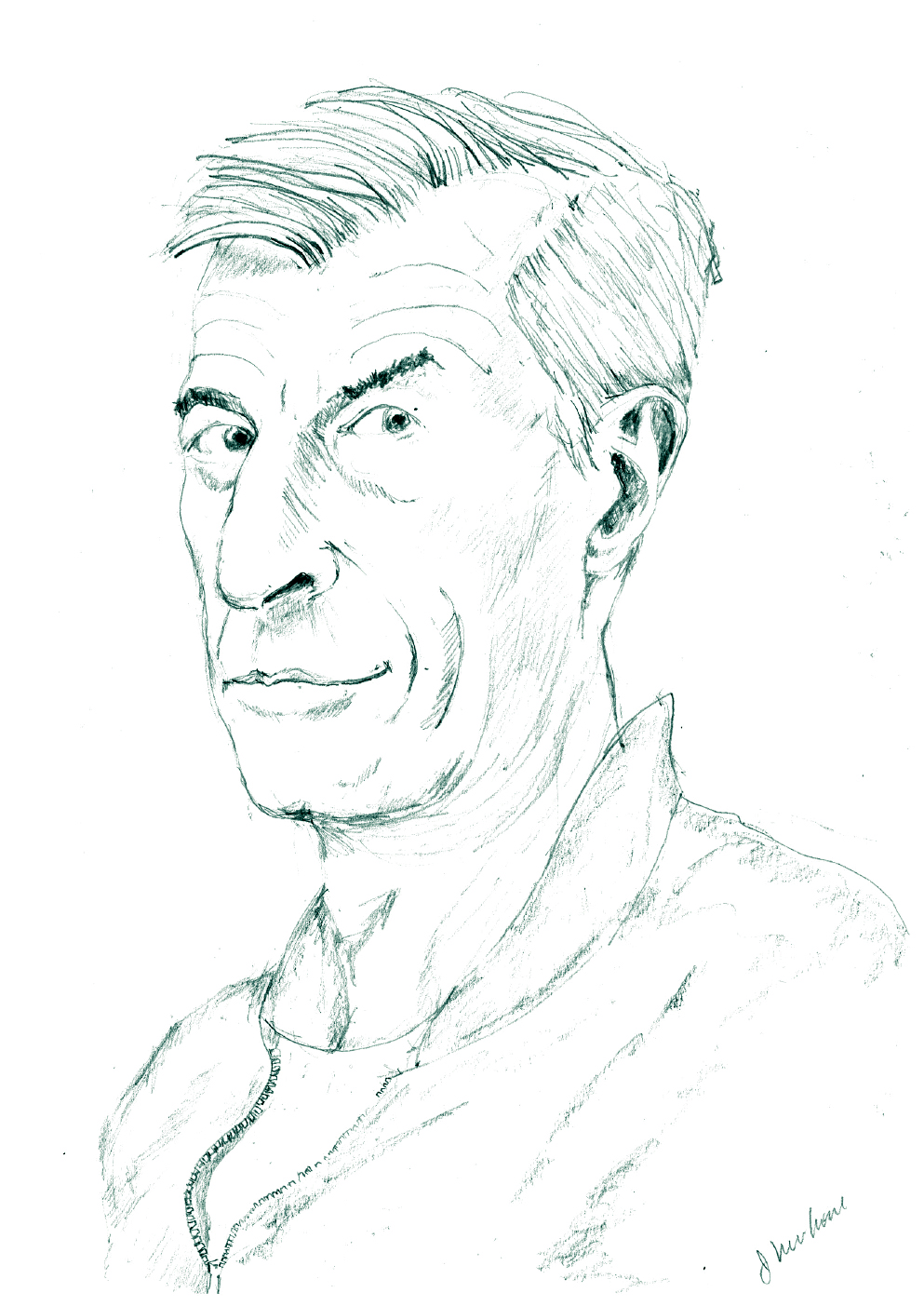

, Italy’s most celebrated living artist, tells Darius Sanai about surrealism, failing at school, and why art can never be a commentary on society. Pencil Portrait by Jonathan Newhouse. Photographic portraits of Maurizio Catellan created for LUX by the artist

Italy’s greatest living artist – and one of Europe’s most celebrated artists of this century – is also something of a philosopher, if you read some of his sharp-tongued musings over the years; or, indeed, if you look at his art. Among Maurizio Cattelan

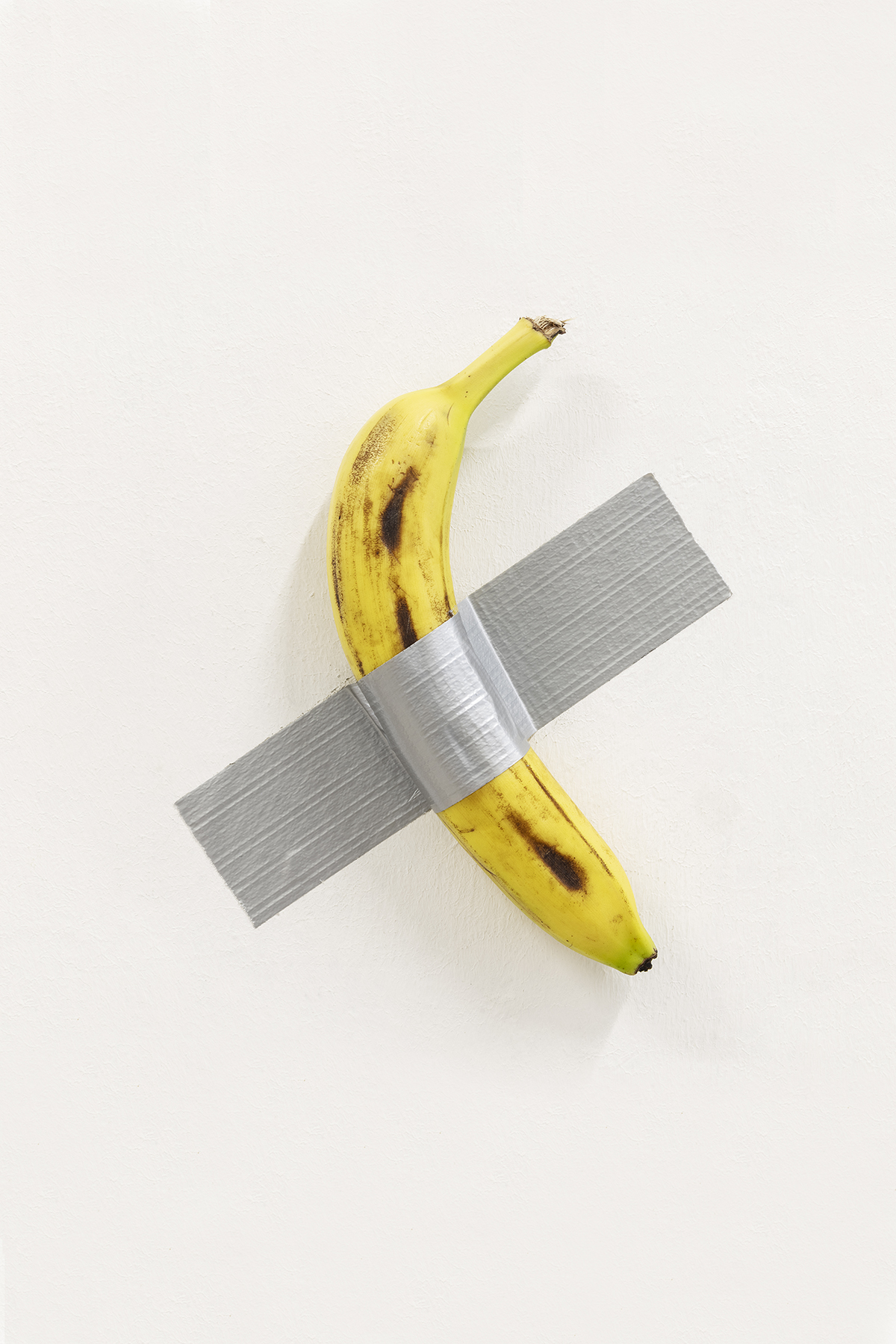

’s most celebrated creations are a solid-gold toilet and a very famous banana taped to a wall in an art fair (which was subsequently eaten by an art student).

Some of his work echoes Voltaire, with its artful, humorous but piercing satirisation of elements of our times – until you examine more closely and wonder what, exactly, is the target of his satire. His biannual magazine, Toiletpaper, which features beautiful, disturbing, engrossing images created with his collaborator, the photographer Pierpaolo Ferrari, could be seen as surreal, satirical or something else entirely.

Speaking with Cattelan is how I imagine it would be like to be toyed with by a mischievous octopus. You think you have an idea of an answer, and then another leg curls round your head from behind and tweaks your ear. The son of a truck driver and a cleaner, with no formal training in art, Cattelan did not shine at school: a million parents around the world would have been forgiven for assuming this son of Padua, northern Italy, was destined not to do anything with his life.

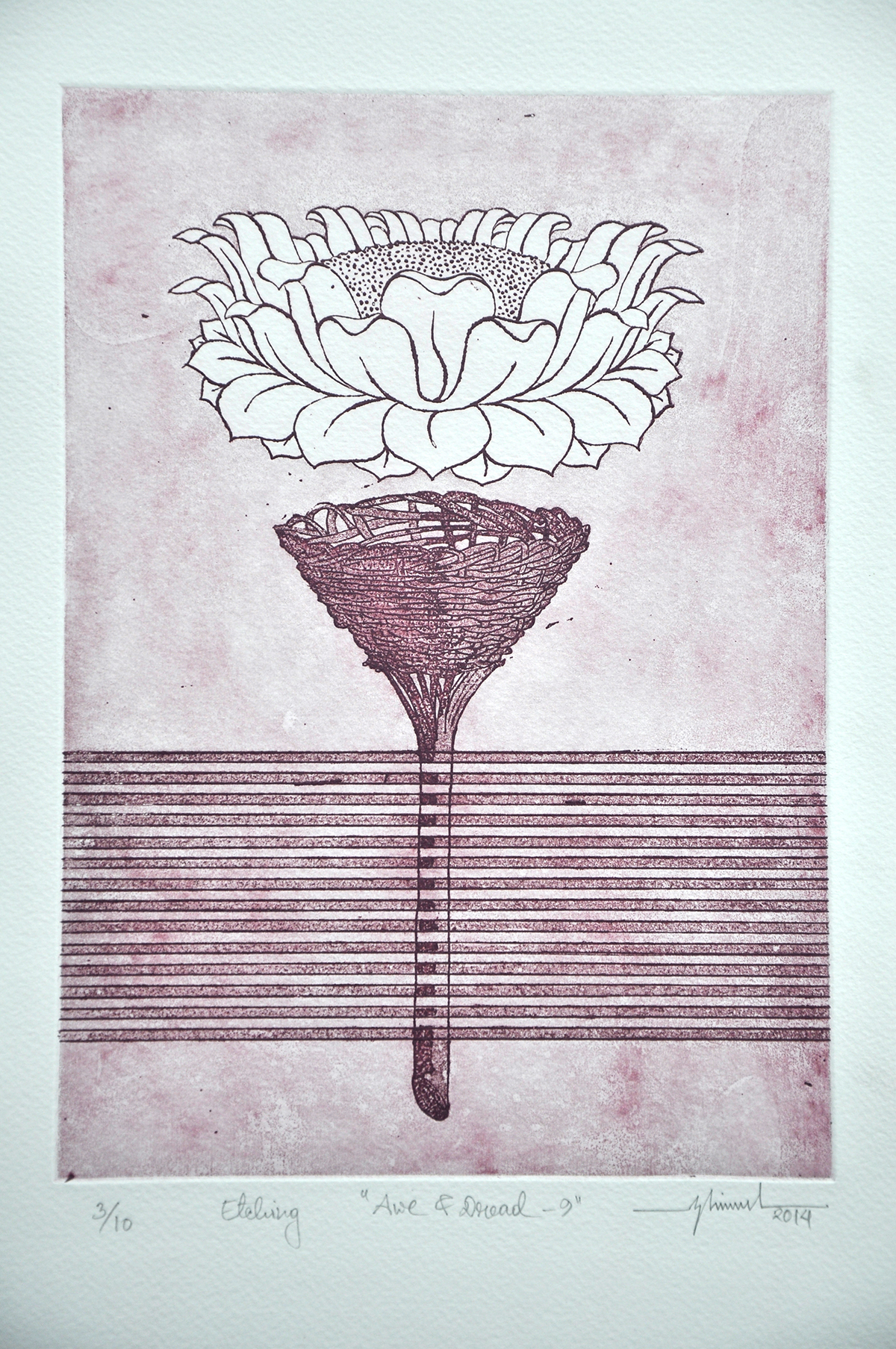

Illustration of Maurizio Cattelan

by Jonathan Newhouse, 2023

And yet his blue-collar parents produced one of the most sophisticated, thoughtful and intelligent artists I have met; and also one of the hardest to pigeonhole. He is not, by his own admission, a painter. Is he a sculptor? An installation artist? A surrealist? What kind of art is a banana taped to the wall, or any of the works he has created on these pages (and on our cover) for LUX? Is he really what his art suggests he is, a mix of Marcel Duchamp, Monty Python and Andy Warhol?

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

After some brain-scrambling and highly entertaining and engaging exchanges, I think I have the answer. But why don’t you read our interview below and come to your own conclusions. Like mine, they will probably be wrong, for Cattelan is a playful yet deadly serious chimera who, as his elementary-school teachers probably said, can never quite be pinned down.

Darius Sanai: Your parents were not in the art world. That must have made it difficult for you to enter the art scene. Did you meet any resistance?

Maurizio Cattelan

: Resistance is not the right word to describe it. The difference between people lies only in their having greater or lesser access to economic possibilities and knowledge, and in being successful in accessing these two elements when the starting conditions do not allow it. All the choices that I have made are aimed at seeking that access. I am a devotee of free will much more than of destiny: in this sense, the Catholic religion has had no influence on me, while the Lutheran heresy is much more in my comfort zone. I am convinced that destiny is nothing but the sum of our choices. Regarding what my parents would have thought of me being an artist, I was lucky enough not to discover it.

DS: What did you want to do when you were at school?

MC: My childhood was not an easy one, but it was not special at all – I share this burden with many people before and after me, who suffered from the same condition. The first memory I have from school was a suspension in first grade. It was an agitated, very proletarian class. I don’t remember why but the teacher wrote in the notebook that I shouldn’t show up the next day. My parents were meant to sign the note from the teacher, but I spent a whole day imitating my parents’ signatures so as not to face their judgment and punishment. They never found out. Also, the report card never arrived at my parents’, because I kept forging their signatures.

Maurizio Cattelan

self-portrait created by the artist and Pierpaolo Ferrari for LUX

DS: You had no formal art training. Does this mean that a great artist needs no training?

MC: Not at all, but it was true for me–art training would have made me give up. The most distressing gift I ever received was a painter’s kit: it had everything I needed to paint, and I had no idea how to use it. It was a year at home that reminded me how inadequate I was as a painter, or at working with my hands in general. It was really frustrating: they were tools that I wanted to try but at the same time I knew I wasn’t able to master them.

DS: You are a satirist, a disruptor. Why?

MC: Please, you tell me, because I feel like the most boring person I know!

DS: Is your art a commentary on society?

MC: Not at all. I’ve always believed that if something can be reduced to one clear concept, it is as sure as hell artistically dead. Art has no direct and unique intent, otherwise it is a problem that has already been resolved, and there’s nothing interesting in this. So, you’ll never hear me affirming a show has one single objective – otherwise, it would be simple advertising. Art is good for you as long as you make whatever you want out of it.

DS: Is one of your aims to create discomfort in those viewing your art? If so, why?

MC: I promise you I have no such nasty aim. I do what I do to deal with my problems, if they create discomfort it is not something planned deliberately. I simply can’t help it.

Maurizio Cattelan

self-portrait created by the artist and Pierpaolo Ferrari for LUX

DS: Who are your forebears? Duchamp? Picasso?

MC: The maximum I can say is that I sometimes dream about finding a bear in my closet. I’m not sure if it is its dimensions or its teeth, but it is quite scary. Imagine if I also had fore-bears!

DS: What effect would you like your art to have on the world?

MC: I would not ask this question in these terms: a flower blooms because its time came, not because there is a reason or effect it can forsee. Similarly, it happens with art, design and all forms of innovation: they happen when the time tis right, it is as simple as this.

DS: Does it trouble you that only the wealthy can buy art that is considered “great” now? What is the relationship between art and its price?

MC: Artworks, art institutions and the art market are linked together, as they form an indissoluble chain that allows the machine to work. Experience teaches us that light cannot exist without darkness and that an ecosystem cannot be balanced if a prey doesn’t have its predator: this is also the case in the art world.

DS: Does it not trouble you that many great works, including yours, are locked in private collections? What can be done to change this (except a revolution)?

MC: It would trouble me if the collectors has no interest in showing them, but since it is in their own interest to show them around as it would increase their value, I don’t see a big issue there. Wise collectors assemble collections that are not purely speculative, and they can be the best companion for an artist. They can help a lot in developing and giving birth to what you have in mind: the fact that you can dream about something because a collector is supporting you opens an entire world of possibilities.

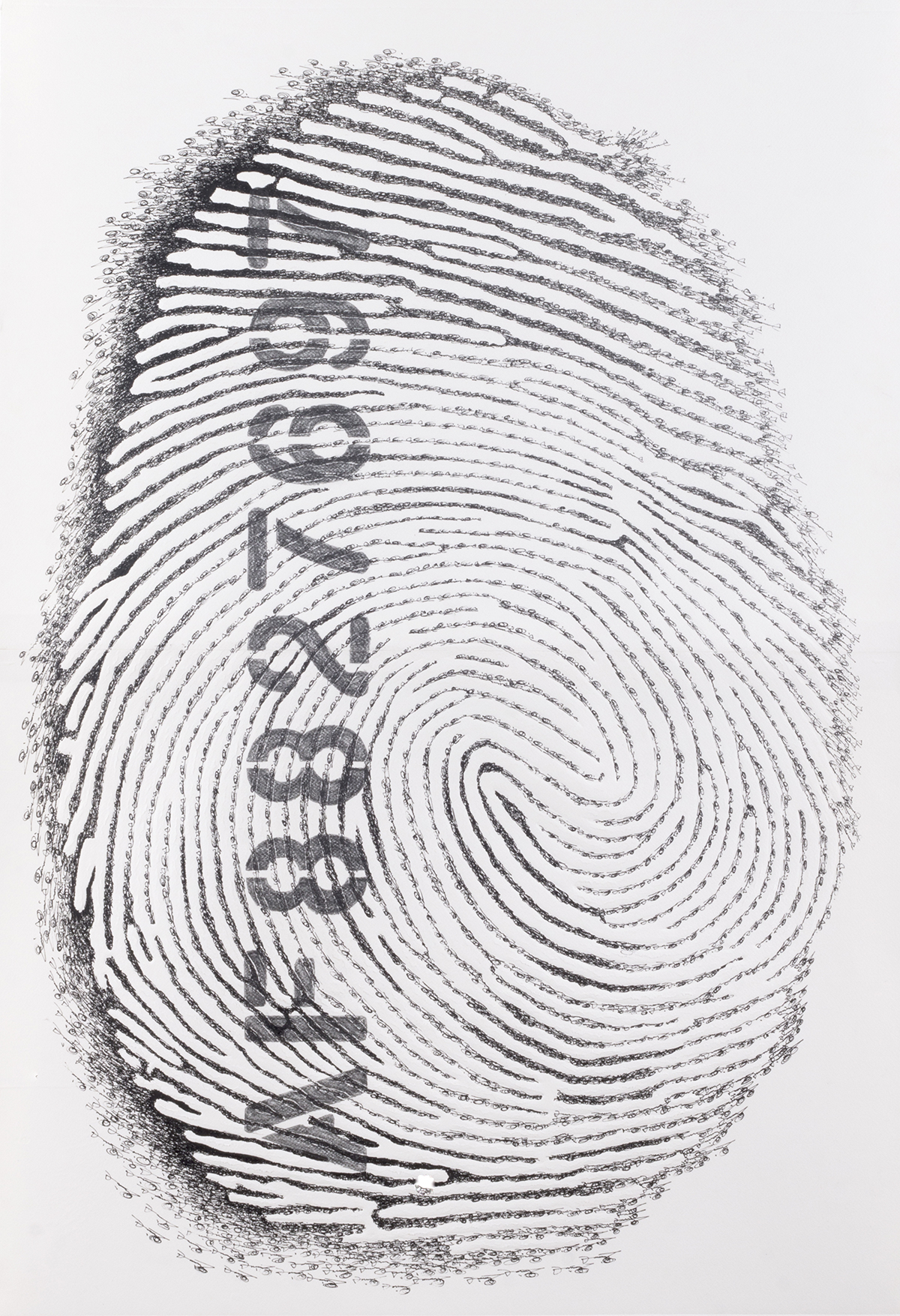

Comedian, 2019, by Maurizio Cattelan

DS: Is revolution a good idea?

MC: It is always a good idea when it’s performed, and not spoken.

DS: Can you describe how you create a work, from inspiration to completion?

MC: My favourite part is the ideation, then I prefer to let others take care of the practicalities, as realisation is a sea I can’t navigate. My contribution is the initial one: the conception of a work is the most interesting part for me, everything is new and exciting. The more you get into the practical phase, the more impatient I become to start with another one: I don’t like the things I already know.

DS: You have said all decoration is disturbing; and yet you have Toiletpaper Home, a homewares line. Should home decoration be disturbing also?

MC: Did I say so? Maybe I was referring to my place; that is totally empty. But I love to think that Toiletpaper images could be applied to home decoration – it has always been a project that knows no limit.

DS: Are you a surrealist? A sensationalist? Absurdist? Or any other kind of “ist”?

MC: I am a 1-ist of contradiction.

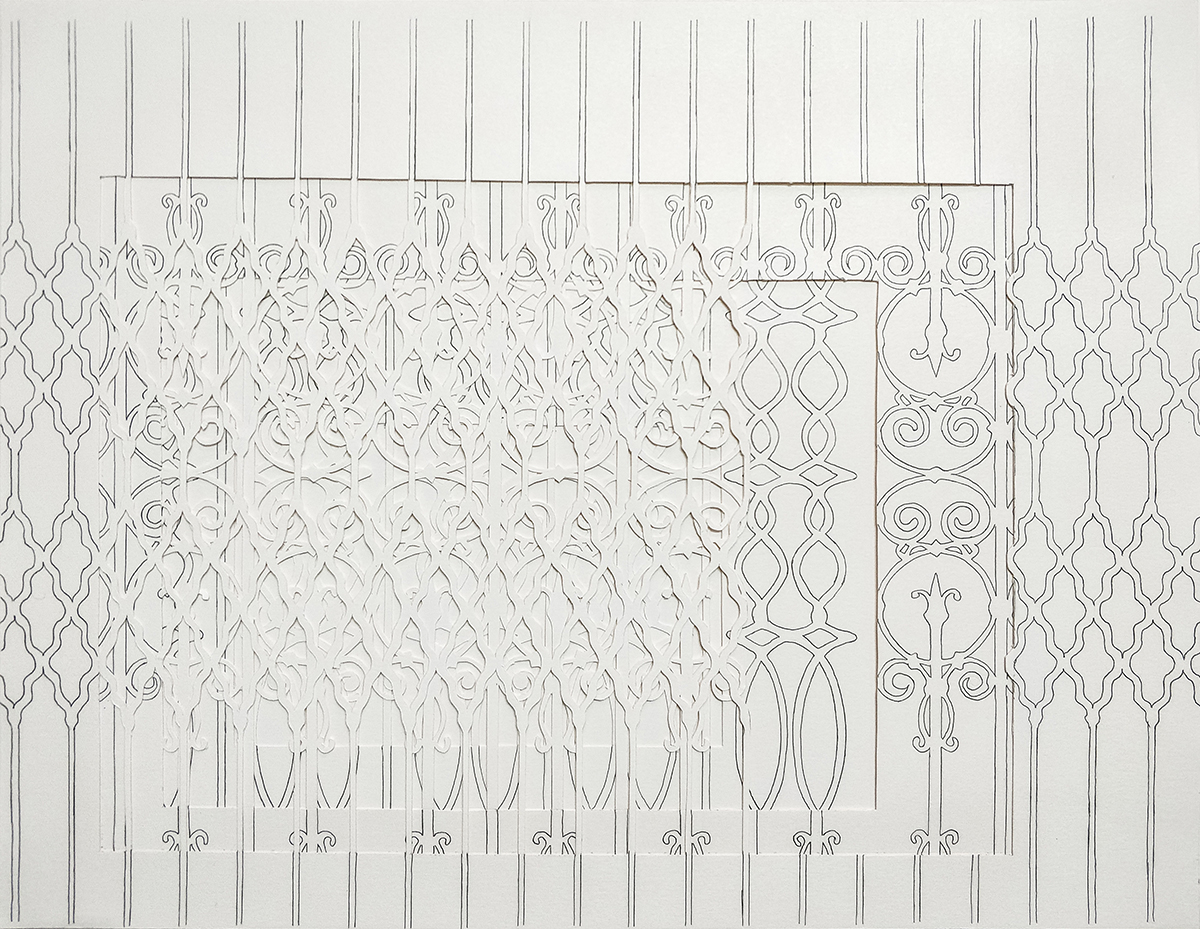

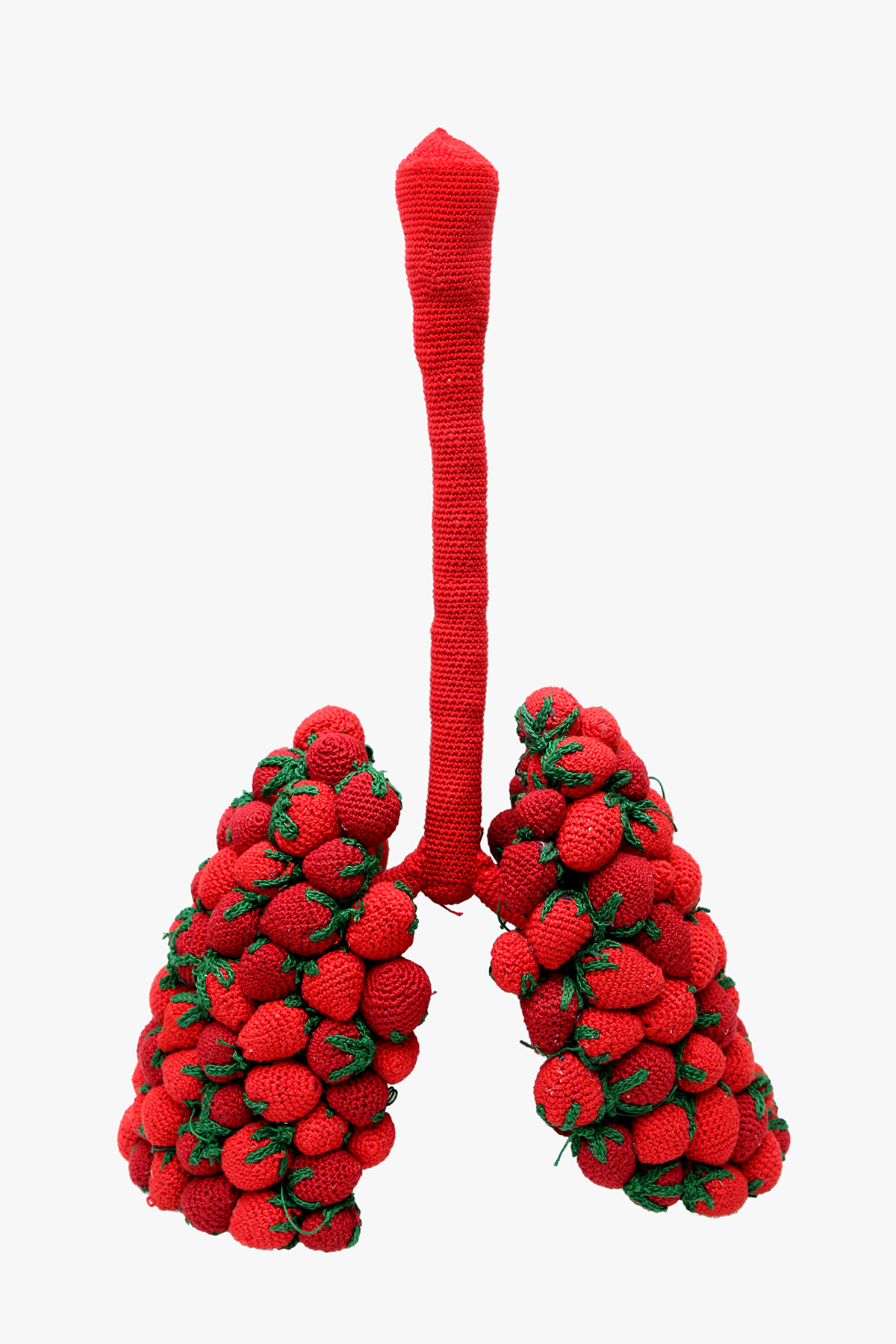

You, 2021, by Maurizio Cattelan

at Massimo de Carlo, Milan, 2022

DS: Is there a morality, a commentary on the human condition or society in your works?

MC: I believe I already answered this, but just to be clear: art should not have a straightforward , unique clear message, otherwise it is advertising.

DS: You have said that if you have been able to amke good art, it’s because of your flaws. What are those?

MC: Le me answer as if I was in a job interview: I’m a perfectionist.

DS: What are your best works of art?

MC: Only time will tell.

DS: Should the banana have been eaten?

MC: Only if next time the peel and tape are also eaten.

Installation view of ALL, 2011, by Maurizio Cattelan

, at Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2011

DS: What role do you think shock value plays in contemporary art?

MC: I wish for every artist’s work to be incendiary, and to never satisfy expectations. In the latter case, it is a style exercise and a waste of time, both for the artist and for the audience.

DS: Your recent collaboration with Gucci explores appropriation and originality. How important is it to be original in the art world today?

MC: Culture has been rewritten many times from many different points of view. If we look at history, copying has been the method of disseminating knowledge as much as in the contemporary world: scribes copied books to ensure future generations had the same knowledge and to preserve their culture over the centuries. A few years earlier, the Romans copied Greek sculptures, as today we copy the great classics and see them in souvenir shops. Copying is a concept as old as humanity, because it is the presupposition of knowledge tout court.

Read more: An Interview with William Kentridge

DS: What about Longchamp, what are you doing there?

MC: It’s a collaboration, a capsule that witnesses the marriage between Longchamp and Toiletpaper. I am looking forward to discovering what the result will be.

DS: Are you a Voltaire of the art world?

MC: You tell me, as I’m not sure of who I am in general, never mind in the art world!

Darius Sanai with Maurizio Cattelan

and Pierpaolo Ferrari

DS: Which artists, living or dead, do you admire most?

MC: All those who did what they did under a sense of urgency.

DS: What or who is overrated in the art world?

MC: All those who did what they did NOT under a sense of urgency.

DS: Will you create digital art?

MC: I’d rather not, I’m far too old for that.

The Longchamp x Toiletpaper Le Pliage collection is at Longchamp stores and lonchamp.com. A limited-edition issue of Toiletpaper features the collaboration.

Photographer: Pierpaolo Ferrari

Art Director: Antonio Colomboni

Set Designer: Michela Natella

Set Builder: Lorenzo Dispensa

Hair and Makeup: Lorenzo Zavatta

Stylist: Elisa Zaccanti

This article first appeared in the Autumn/Winter 2023/24 issue of LUX

Recent Comments