Dilara Begum Jolly, Parables of the Womb. Image courtesy of the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

Barrister A B M Hamidul Mishbah, who specialises in Intellectual Property (Copyright & Visual Art) and Technology Law writes about three historic derivative artworks from the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation’s extensive collection, and provides insight into the complex issues of copyright and ownership in the art world

“I walk, I look, I see, I stop, I photograph” said Leon Levinstein. Every element of an artistic or creative work, be it a photograph or a painting, weaves a tapestry of ingenuity. The pursuit of collecting such artistic or creative works is a testament to the realities we encounter in our lives.

“Parables of the Womb”, acquired and preserved by the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation (DBF), is a series of portraits of Birangonas (War Heroes) of the 1971 Liberation War of Bangladesh. The masterpieces were created by Dilara Begum Jolly, acclaimed artist, painter, and sculptor in Bangladesh. Jolly rejuvenated original photographs to commemorate the plight experienced by women during the troubled times of the Liberation War.

The artworks consist of reprinted photographs of the Birangonas (War Heroes), adorned with needlework, achieving the status of ‘derivative work.’ Derivative work is a form of creative expression spawned from pre-existing original work that contains substantial transformation in line with the creator’s vision. As a result, it receives the protection of copyright law and allows the creator to control her integrity and commercial interests.

Andy Warhol, Ingrid Bergman, Edition 10/30. Image courtesy of the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

Andy Warhol, perceived as one of the pioneers of Pop Art, created the artwork “LIZ” in 1963. The “LIZ” series comprises several paintings devised from Elizabeth Taylor‘s publicity photograph for her film ‘Butterfield 8.’ Andy Warhol used a method of silkscreen printing, and the series showcases Warhol’s signature style of vibrant and bold colours blended with contrasting hues to highlight the artist’s fondness for fame, iconic personalities, and celebrity culture. The series remains a significant part of Warhol’s enduring legacy, speaking to the relationship between art, commerce, and mass media, inspiring the artists and audiences of this age. One of the artworks in the series of derivative works, is another jewel of the DBF’s collection.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Atul Dodiya, one of the most coveted contemporary artists in the Indian subcontinent, rose to prominence in the late ’90s for a series of artworks he created on Mahatma Gandhi. One of the artworks from that series depicts Mahatma Gandhi and Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose engrossed in a deep conversation, created using a public domain photograph dating back to 1938. The original photograph was captured during a session of the Indian National Congress in Haripura, marking the first resolution after regaining India from the British Raj.

The artistic rendition created by Dodiya is a sepia-washed watercolour painting, immortalising the historic moment that paved the way for India’s liberation and commemorates the significant roles played by the two iconic leaders. The DBF steadfastly preserves this piece.

Atul Dodiya, Noakhali, November 1946. Image courtesy of the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

Original photographs enjoy copyright protection under copyright law. Copyright protection for photographs begins the moment the image is created, i.e., fixed onto the film negative through the camera’s shutter click. The person who captures the photograph is considered the ‘author’ and becomes the first owner of the photograph’s copyright, enjoying exclusive rights, including the right to reproduce (copy, print, download, etc.), the right to communicate to the public, create derivative works, and the right to prevent unauthorised use by third parties.

This means the original photographs, whether portraits of the Birangonas, Taylor’s publicity photograph from the film ‘Butterfield 8,’ or stock images from the 1938 session of the Indian National Congress in Haripura, were standalone works created by independent photographers. These photographers are presumed to be the authors and owners of the copyright in those photographs unless there is covenant to the contrary; the portraits are unequivocally not orphan works.

Maurizio Cattelan

has said: “Culture has been rewritten many times from many different points of view. If we look at history, copying has been the method of disseminating knowledge as much as in the contemporary world: scribes copied books to ensure future generations had the same knowledge and to preserve their culture over the centuries. A few years earlier, the Romans copied Greek sculptures, as today we copy the great classics and see them in souvenir shops. Copying is a concept as old as humanity because it is the presupposition of knowledge tout court.” This philosophy that resonates with Rabindranath Tagore‘s school of thought on ‘moner mukti’ (indulgence of the mind). This is the juncture where the law intersects with creativity and innovation.

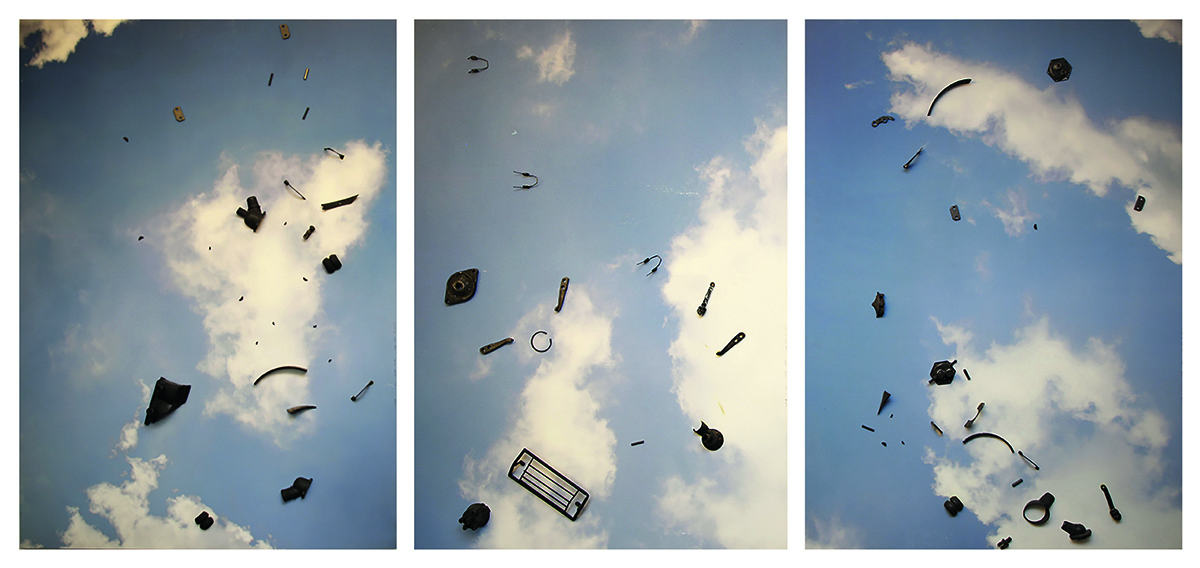

Shilpa Gupta, Unnoticed, 2017. Image courtesy of the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

Creating derivative works from original photographs is permissible if endorsed by, and without prejudicing the interests of, the original author. Some jurisdictions are accommodating to derivative works created for certain purposes under the principles of ‘fair use,’ without the original author’s permission, taking into account the underlying purpose, nature, extent, and potential impact of the derivative work.

Read more: Syed Muhammad Zakir’s imagined city of Baghreb

By and large, artistic works create bridges that connect our past, present, and future, reminding us of the timeless beauty and relevance of human creativity. Artistic works such as “Parables of the Womb”, the “LIZ” series, and Dodiya’s paintings have the innate ability to evoke emotions, resonate the connection between art and human experience, and ignite the passion for collecting and celebrating art.

Firoz Mahmud, part of a photograph series, ‘Soaked Dream’. Image courtesy of the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

The interplay between copyright protection for photographs, derivative works, and digital artistic assets has become remarkably intense in the age of NFTs, which consistently push the boundaries. NFTs have revolutionised the concept of ownership and the domain of collecting and preserving art. Owning an NFT and owning a copyright are not the same. Copyright law does not confer any rights to the NFT owner, but the NFT owner may use ownership to exert substantial control over an NFT. This control is not automatic; two separate rights come into play here—the right to own a single copy of the artistic work, and the right to make copies and generate derivative works from the original work. NFT technology enables broader access to innovative creations. Collectors of artistic works can now play a transformative role and foster a dynamic ecosystem that blends artistry and commerce in ways never seen before, while the tokenisation of artworks into NFTs opens new streams for generating revenue.

Nonetheless, collectors remain custodians of history. It’s not the financial gain but the narratives woven by the creators that motivate most collectors. They dedicate themselves to safeguarding artworks as a testament to the evolving journey of humanity. Each piece of artistic work encapsulates a moment frozen in time. With every piece of work, artists breathe life into their visions, and collectors, in turn, take on the responsibility to ensure that these visions endure for generations.

Firoz Mahmud’s photograph series, ‘Soaked Dream’, is a project about performative refugee, displaced and migrant families, being progressed between 2015-2021. Image courtesy of the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

The acquisition and conservation of artistic creations like “Parables of the Womb”, the “LIZ” series, or Dodiya’s watercolour paintings by a collector passes down our narratives to the generations to come.

This article was published in association with the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

Recent Comments