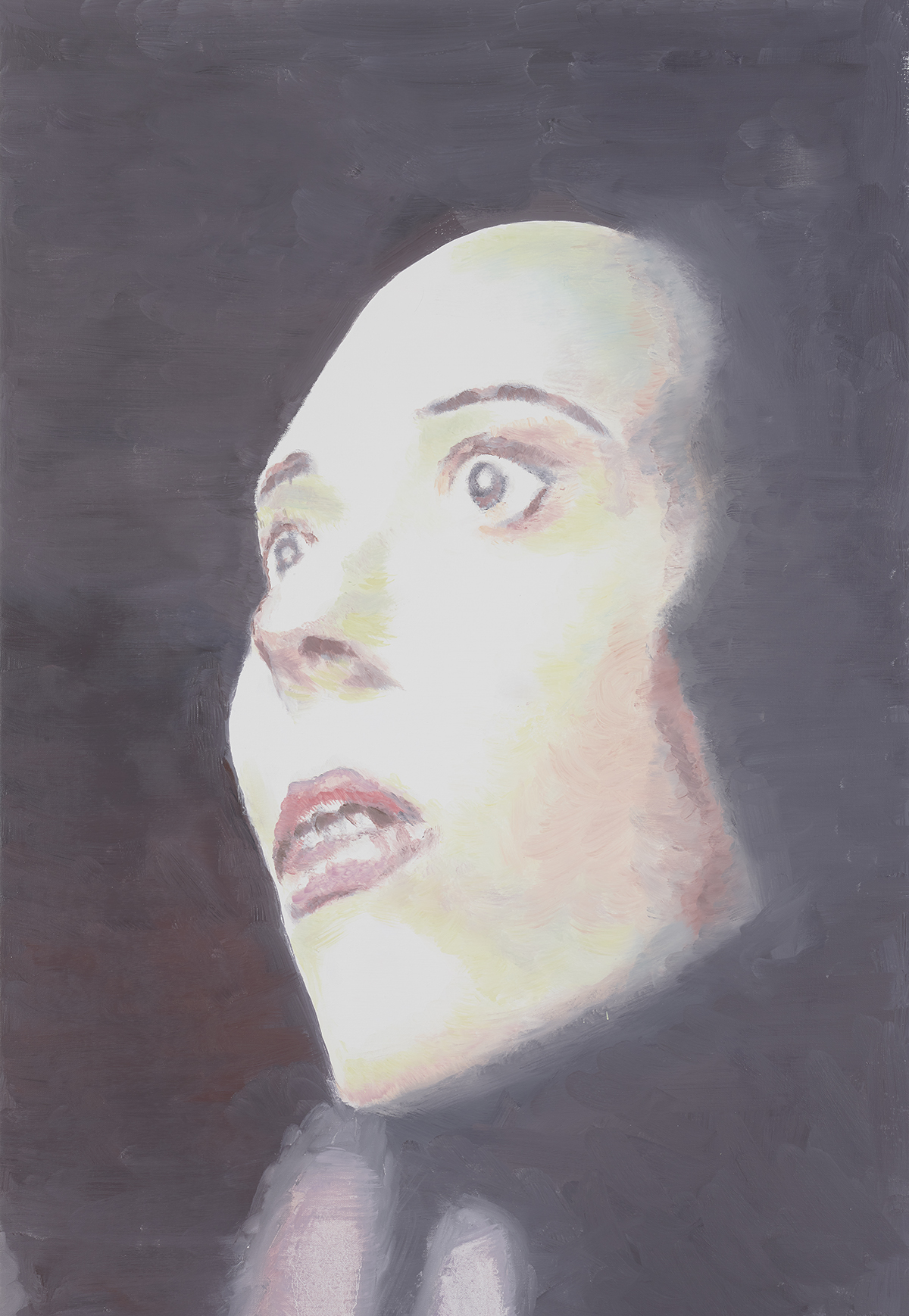

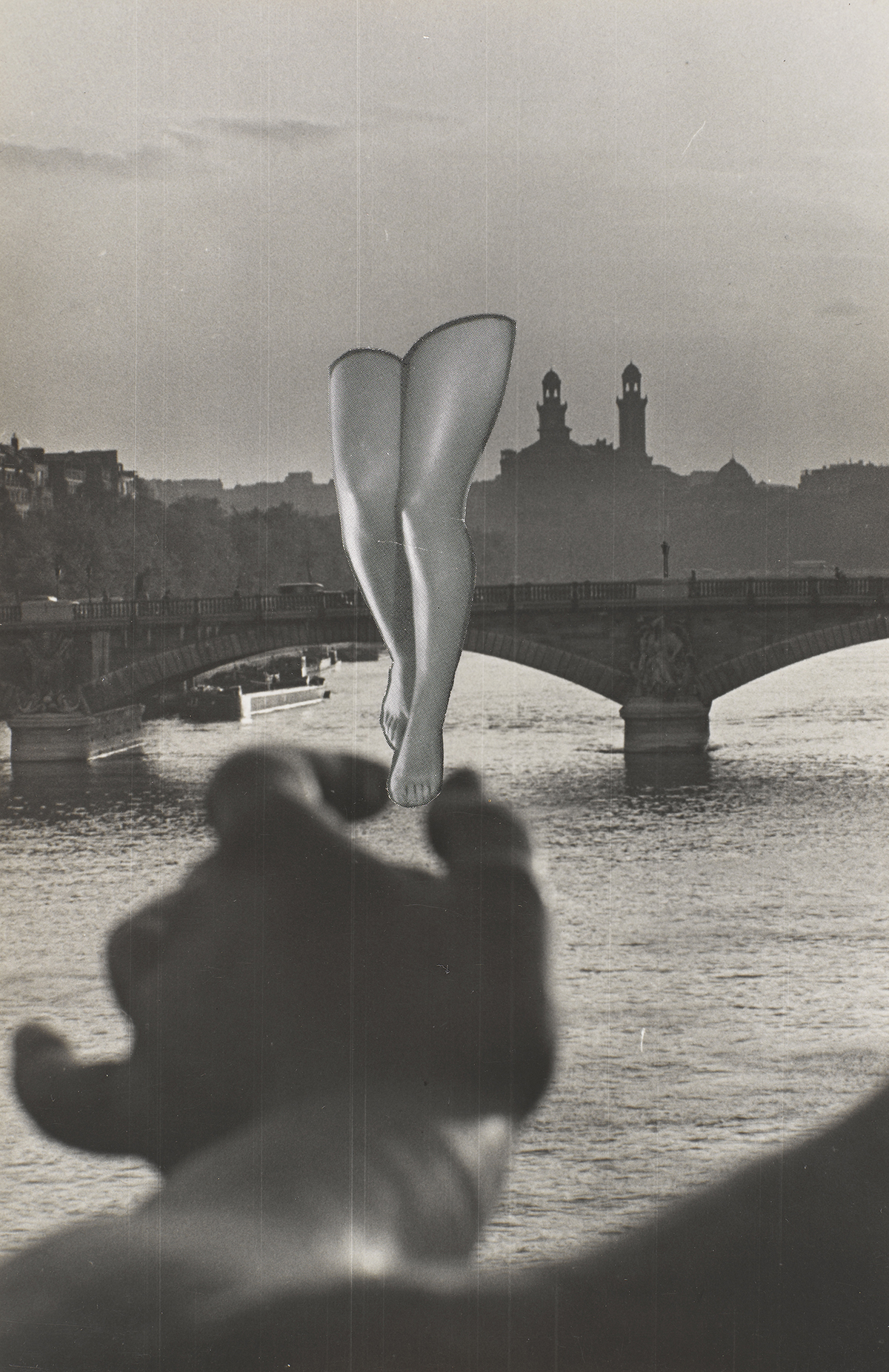

‘Twenty Seventeen’ (2017), by Luc Tuymans, Pinault Collection

Favouring themes of conflict, violence and death, renowned Belgian painter Luc Tuymans fulfils the brief of brooding artist, yet his work is deeply layered and complex. With two major retrospectives on his work being held in Europe this year, Millie Walton meets the man behind the canvas

The artist in his Antwerp studio

Through a garage door and down a wide passageway: a man’s bleached face stares blankly ahead with large, piercing eyes. To the right, there are two more enormous pale faces. “These are dead people,” Luc Tuymans says of the series of three portraits hanging in his studio in Antwerp. They will soon be shipped off to form part of his upcoming show at De Pont Museum of Contemporary Art in the Netherlands, one of two major retrospectives this year. We sit on two sagging armchairs; there’s a small table between us with a cup of cold black coffee and in front of us, another much smaller painting of a ghostly, hooded figure tacked onto the wall with masking tape. It’s a present for the director of De Pont, Tuymans tells me, lighting up the first of many cigarettes. Apart from the paintings and a table stacked with paper and dried-up paint mounds, the studio is stark, almost blindingly white in the sunshine. A former laundrette, Tuymans bought it over ten years ago, having previously worked in a much smaller apartment, which looked “more like Francis Bacon’s studio”. This place, he says, is, “antiseptic, but it works well”.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

The Belgian artist famously completes most of his works in one day, giving the impression of a feverish outpouring of creativity, but really the works have been brewing for some time, often for months, before Tuymans applies paint to canvas. For him, the process begins with a careful curation of pre-existing imagery, drawings, Polaroids and photos he takes on his iPhone, or things he encounters online. He selects his source material according to its relevance and paintability, by which he means, “what kind of kick I can get out of it”. Considering that much of his subject matter is violent, morbid or at the very least, deeply cynical, we might consider these ‘kicks’ to be somewhat sadistic.

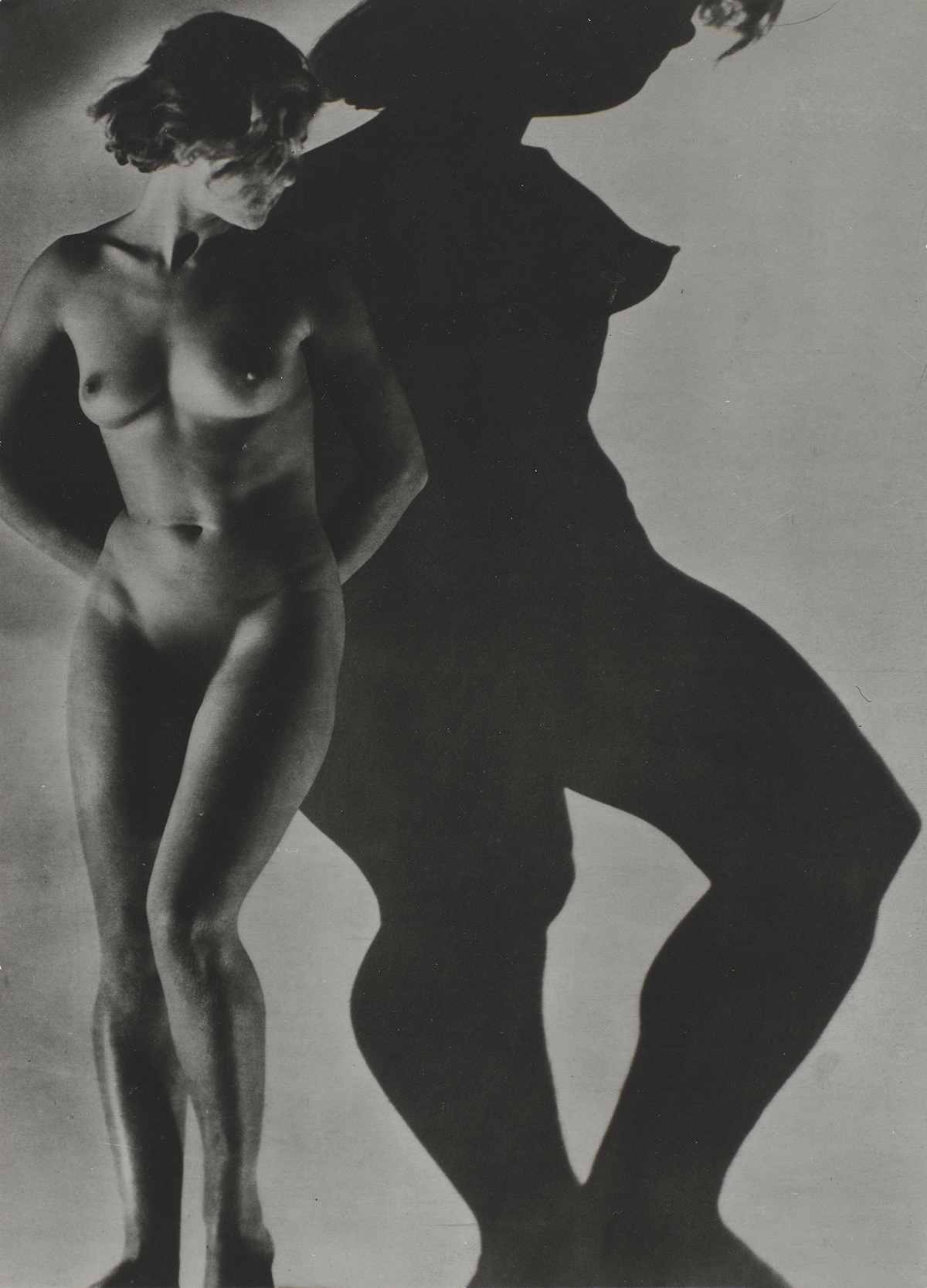

‘Disenchantment’ (1990), by Luc Tuymans, private collection

Right from the start of his 40-year career, Tuymans has been depicted by the media as the brooding artist, in part due to his intimidatingly large physical presence and flickering eyes, but also because of his ongoing fascination with the darker corners of European history and reluctant approach to beauty. Speaking of his current retrospective exhibition at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, he laughs growlingly at the idea that people might consider his paintings beautiful. In the press video for the show, he is depicted as a stereotypical villain lurking in dark alleyways and brandishing his paintbrushes as weapons. It says a lot that Tuymans himself made the short film.

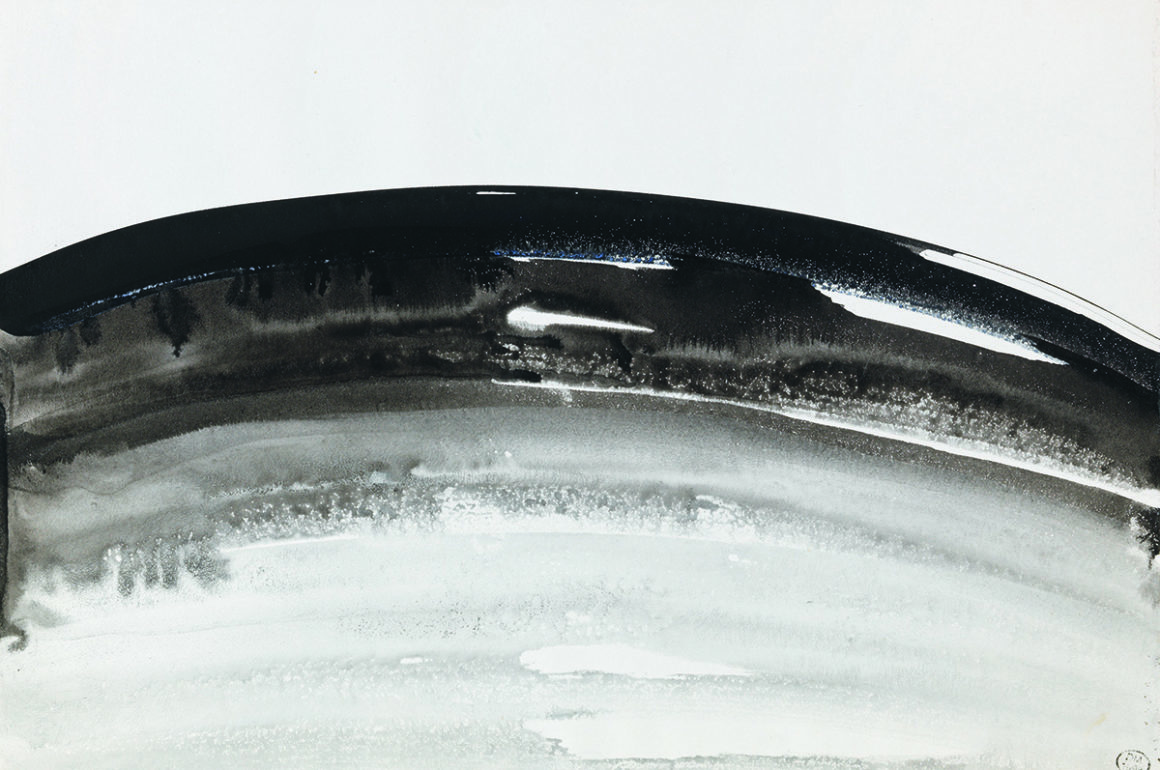

‘Die Zeit (pt 4/4)’ (1988), by Luc Tuymans, private collection

And yet, something in Tuymans tells you not to trust appearances. Just as his paintings may appear prosaic in their imagery, their significance is deeply layered. To view his work is to enter into a game in which you neither know the rules nor the aim. “You could actually see my work as the deep web, or the precursor of it,” says Tuymans with a slight smile, making it hard to gauge how seriously to take such statements. Nevertheless, his practice is certainly preoccupied with peripheries, hidden objects and meanings, things the ordinary eye would ignore or miss. There is a tension in his paintings between uncovering and disguising, remembering and disremembering. As with the series of cadaver portraits, his subjects often seem to be disappearing, fading from memory and simultaneously, clinging desperately to life.

Read more: The new age of Chinese ink art

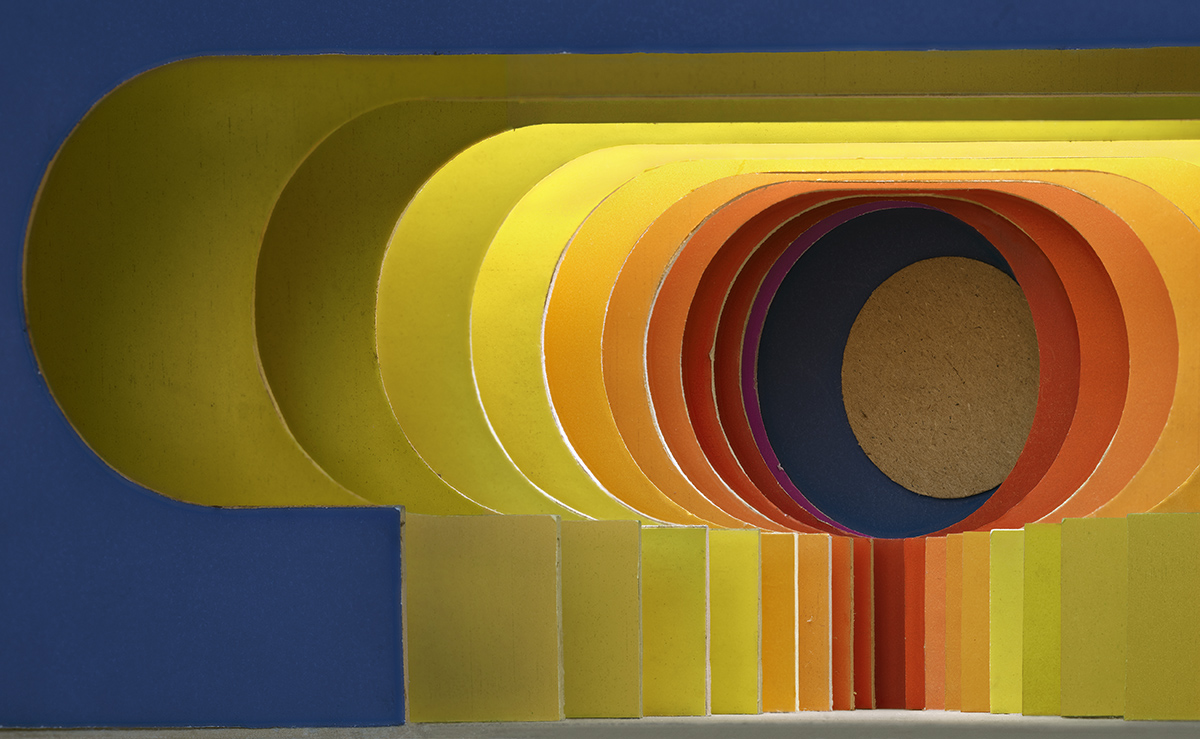

‘Allo! I’ (2012), by Luc Tuymans, private collection

“From very early on, my work was born out of an insane and very profound distrust of imagery,” he says, which is now especially relevant in the age of the digital image and mass reproduction – where the lines between originality and forgery are increasingly blurred. This distrust, in fact, was the reason Tuymans started painting as a teenager in the late 1970s, seeking a deliberate ‘regression’ by creating a work that had the appearance of another era and thus, developing a practice of so-called ‘authentic forgery’. However, this seems somewhat reductive to Tuymans’ intentionality, which is one of total disillusionment. Take, for example, the mosaic of pine trees that covers the floor in the entrance hall of Palazzo Grassi. Visitors might be forgiven for assuming it to be part of the Palazzo’s grand decoration rather than an act of wilful deception by Belgium’s most famous contemporary painter, who worked with an Italian firm to perfectly match the green marble to the existing floor colouring. Then there’s the fact that the mosaic is based on Tuymans’ iconic 1986 painting Schwarzheide, named after a Nazi labour camp where many inmates were worked to death. This seemingly picturesque cluster of pine trees represents the evergreens planted along the border of the camp to hide it from public view.

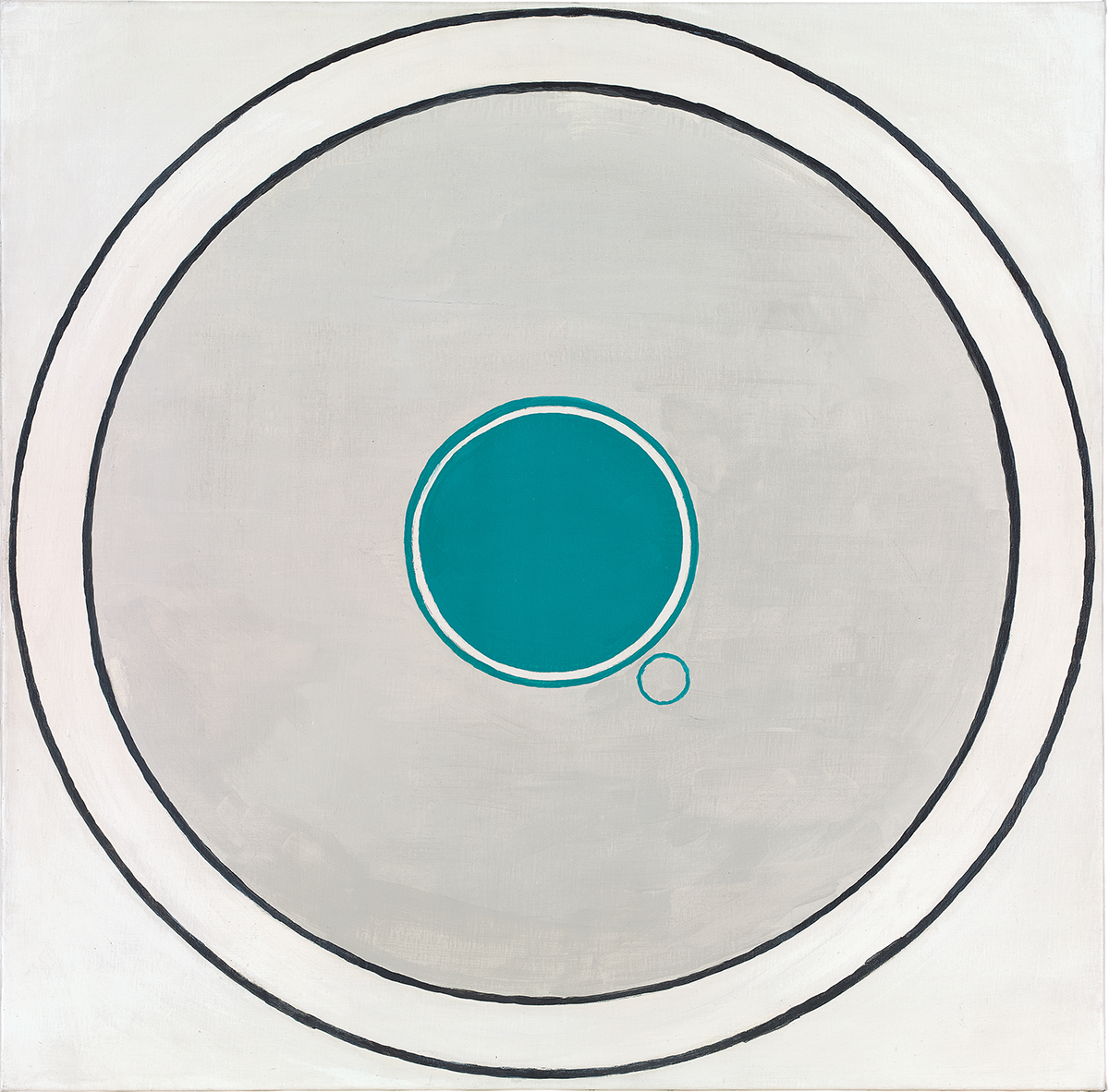

‘Technicolor’ (2012), by Luc Tuymans, private collection

‘München’ (2012), by Luc Tuymans, Pinault Collection

Encountering works such as these for the first time, how can we know or begin to understand their embedded contexts? “I am a big believer in not overestimating or underestimating the public,” says Tuymans. “I don’t believe in wall texts. You’re given a reader, which you can choose to look at whenever you like, but there is a point I’m trying to make in the experience through which you have a feeling of not just oblivion, but utter ignorance.” This comes from the fact that the exhibition at Palazzo Grassi, titled La Pelle after Curzio Malaparte’s book of the same name, is a retrospective show in one of the world’s most visited cities, so the audience being addressed is the wider public rather than art experts. Tuymans notes that many viewers may be drawn not by the art, but by a “certain kind of voyeurism to get into spaces such as the Palazzo”. He relishes the idea that the exhibition may disrupt their expectations, functioning as “a strong confrontation with the space”.

Read more: Photographer Viviane Sassen’s ‘Venus and Mercury’ at Frieze London

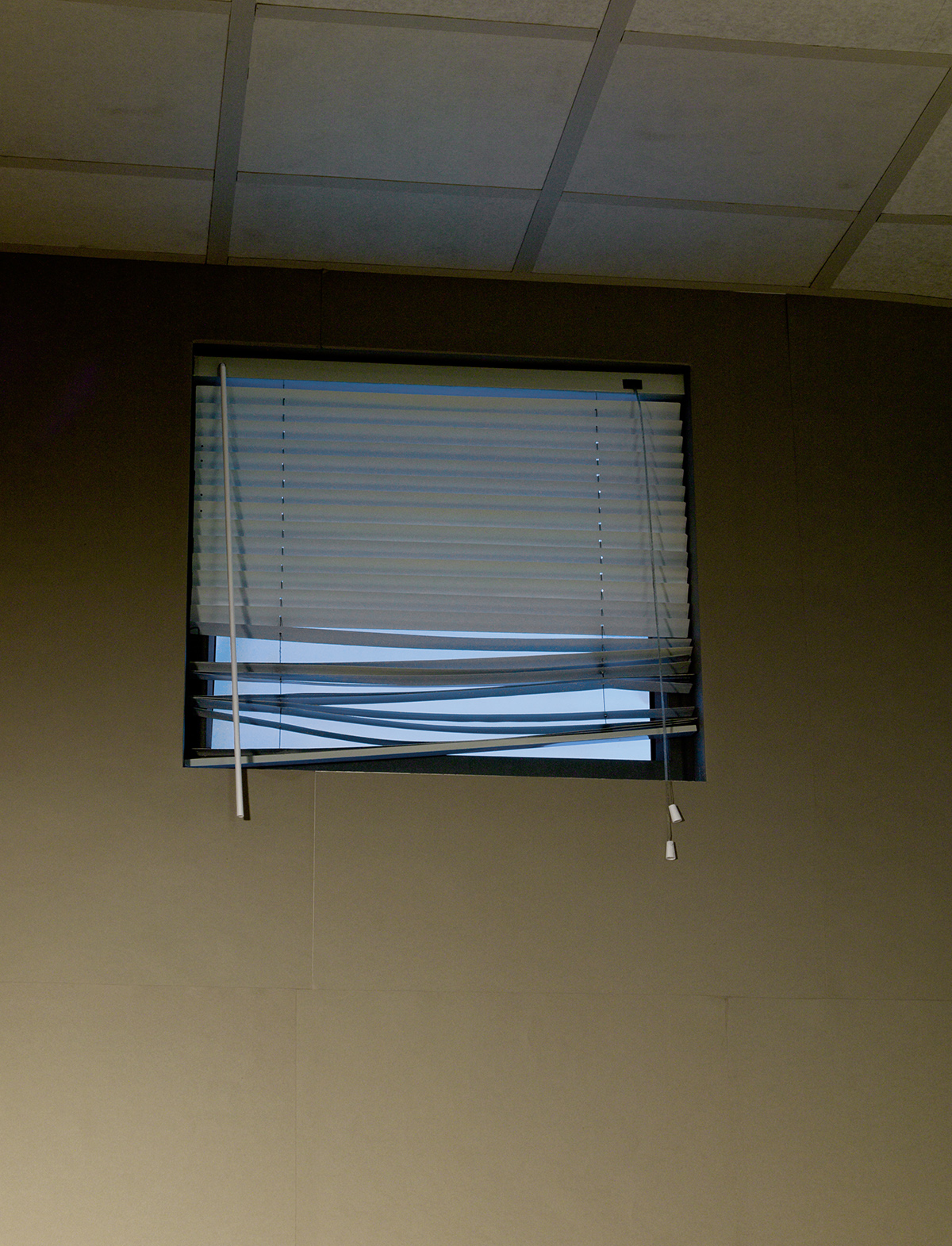

Installation from ‘La Pelle’, ‘Turtle’ (2007), by Luc Tuymans, private collection

Does he think of himself as a political painter, then? “No artist can be political because you can’t load up an artwork from the start, if you do, you’re just making propaganda,” says Tuymans. “But that doesn’t mean the work cannot have a political stance at a certain given moment.” Whether his paintings work or not, in his opinion, has a lot to do with the images that surround him. “I need an extreme tension when I paint,” he claims, also referring to the anxiety that he feels each time he approaches the blank canvas. There are conditions for his creative process: Thursdays and Fridays only (“because it’s the end of the week”), a clear head (“no drinking the night before”) and a sense of risk. “I think that fear of failure is very necessary,” he says. “Otherwise I may as well do a 9-to-5 job.” Of course, failure is a less painful prospect when you’re one of the world’s most respected painters. Now, Tuymans has the luxury of “throwing away” a painting when it’s not working, and by that he means literally into the bin. Antwerp residents, take note.

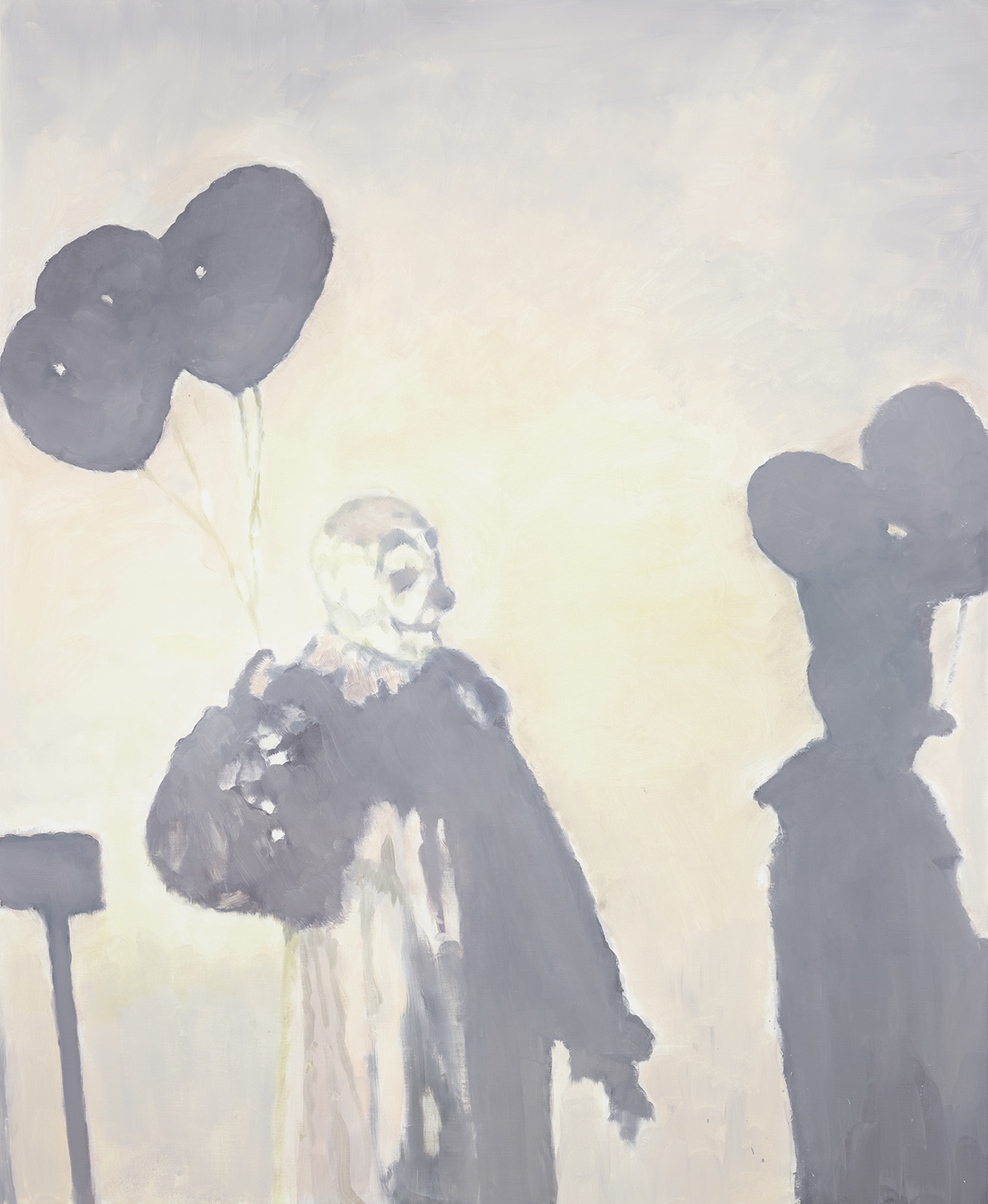

‘Ballone’ (2017), by Luc Tuymans, private collection.

“Whenever I’m asked the question: why do you still paint?,” muses Tuymans, “the answer is always: because I’m not f*cking naive. Painting is a medium that works within its own proposition with time and it’s always had this inheritance of being an anachronism within that time, which has an appalling impact on your brain.” The impact he speaks of relates again to the multilayered aspect of his work, to the way in which he both draws from and mimics the past, while simultaneously and inevitably applying his contemporary, subjective perspective. It is this perspective, combined with the cultural context in which the work is viewed, that creates its relevance. So the significance of Tuymans’ paintings – as perhaps with all artworks – is continuously reforming. “I’m currently working on a two-year project with three scientists,” he says. “We’re going to put [my] work into algorithms. Not to make a painting with a computer, because that’s stupid, but to see what the signifiers mean in terms of language. Language is something that is always changing and the aim is to compare that to the anachronism of painting and to see what the outcome would be.” Admirers of his work will anticipate this next incarnation with interest.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 19 Issue.

Recent Comments