Chong Huai Seng is one of Singapore’s most respected collectors. He and his daughter Ning Chong, a first mover in art investment advisory, speak with LUX Leaders and Philanthropists Editor Samantha Welsh about the future of art as an investment of passion

When international banker Chong Huai Seng started buying art in the 1980s, he could not have imagined growing a collection that would catalyse a forum for South East Asia’s prominent collectors, artists and experts; nor that in co-founding a gallery The Culture Story with his daughter, Ning Chong, she herself would see a gap for a specialist art investment advisory and would go on to found the Family Office for Art (FOfA). Father and daughter share their approach and insights into dealing with passion assets such as art

When did your collecting journey start?

Mr Huai Seng Chong: My collecting journey started in the mid 80’s when I was a stock broker and I used to travel to London frequently for business trips. I loved traipsing around Mayfair, dipping in and out of galleries. I started buying British sculpture and Russian paintings, very unusual because most people start buying art from their own country. I was merely responding to what I like, my daughter likes to call it “retail therapy” at a time before the internet, and all you had, was to trust your instinct and sensibilities.

Nina Chong: About seven years ago, I introduced some governance to my father’s art collection, cataloguing and art collection management and to assess the strengths of the collection and where we should focus our future acquisitions. With that, we are able to identify themes within the collection, and Dad always enjoys selecting and curating the pieces which we put up in our private gallery The Culture Story. Personally I started my own collection a mere two – three years ago. I realised I had a point of view, which was different from my father’s and there were certain artists and themes which resonated more strongly with me, as a new mother, as an entrepreneur.

Mr Huai Seng Chong and his daughter Ms Ning Chong are two of Singapore’s most respected collectors.

How did you decide a career as an art professional was for you?

CHS: Art collecting started as a hobby for me, almost forty years ago! I never thought this is something I would continue to do, and now this hobby has turned into a business venture between me and my daughter. This is something we did not plan to do, but I’m happy that we are on this adventure together.

NC: When I was young, I was surrounded by works of art and as a family we used to follow my Dad to visit galleries on the weekend. It was only after graduation, when I didn’t want to pursue banking or finance that my father nudged me to consider the art world. I did my own research, including a few internships in London before I decided that I would commit and pursue a career in the arts. It took me a long time to get to where I am, looking back it has been very rewarding to work in different areas such as art fairs, auction house, galleries to government policy work, it has given me a very comprehensive overview of the art ecosystem.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

What was the vision behind The Culture Story?

CHS: We started The Culture Story in June 2017 as a private gallery, like Gertrude Stein salon’s setting in her Paris apartment in the 1920s where artists, poets, writers, thinkers would get together and make merry. For us, we wanted to create a cosy environment where we can share works from our family collection, and encourage other collectors to collaborate with us. By organising exhibitions and hosting talks with artists, collectors and art world professionals, The Culture Story aims to promote greater understanding and discourse around art and foster connoisseurship.

How has the mission and collection evolved?

CHS: We are still very much following the mission we set out for The Culture Story at the beginning. The Singapore art scene has matured significantly and we are at a stage where other art collectors are open to collaborate with us. They are happy to share work(s) from their private collection, especially when they encounter feedback from members of the public, students or other art collectors and professionals.

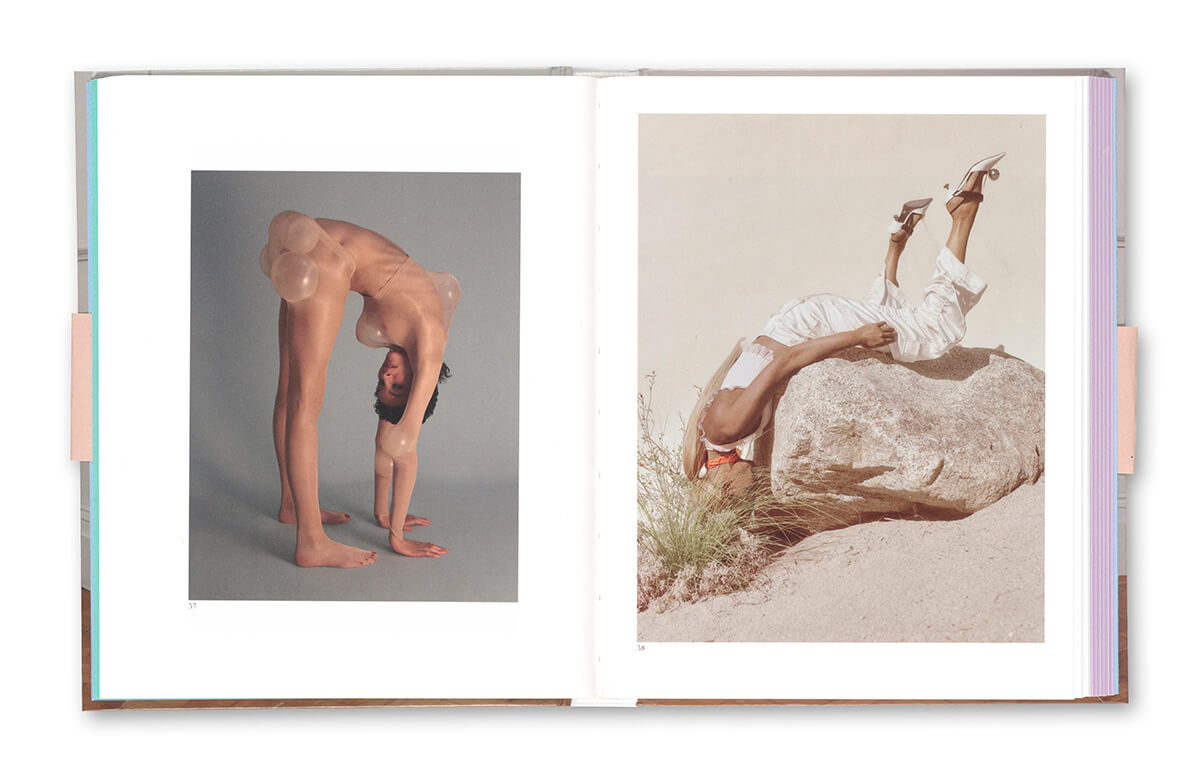

“Collecting Bodies: a short story about art and nudity in Asia” with works on loan from 10 art collectors

NC: We try to focus on a few themes amongst our family collection. Recently, we have loaned some of our works to museums for various exhibitions. One in particular is an early Kim Lim sculpture which is currently on view at the Hepworth Wakefield Museum in Yorkshire, United Kingdom. Later this year, the entire exhibition will travel to the National Gallery Singapore for her long-await retrospective exhibition.

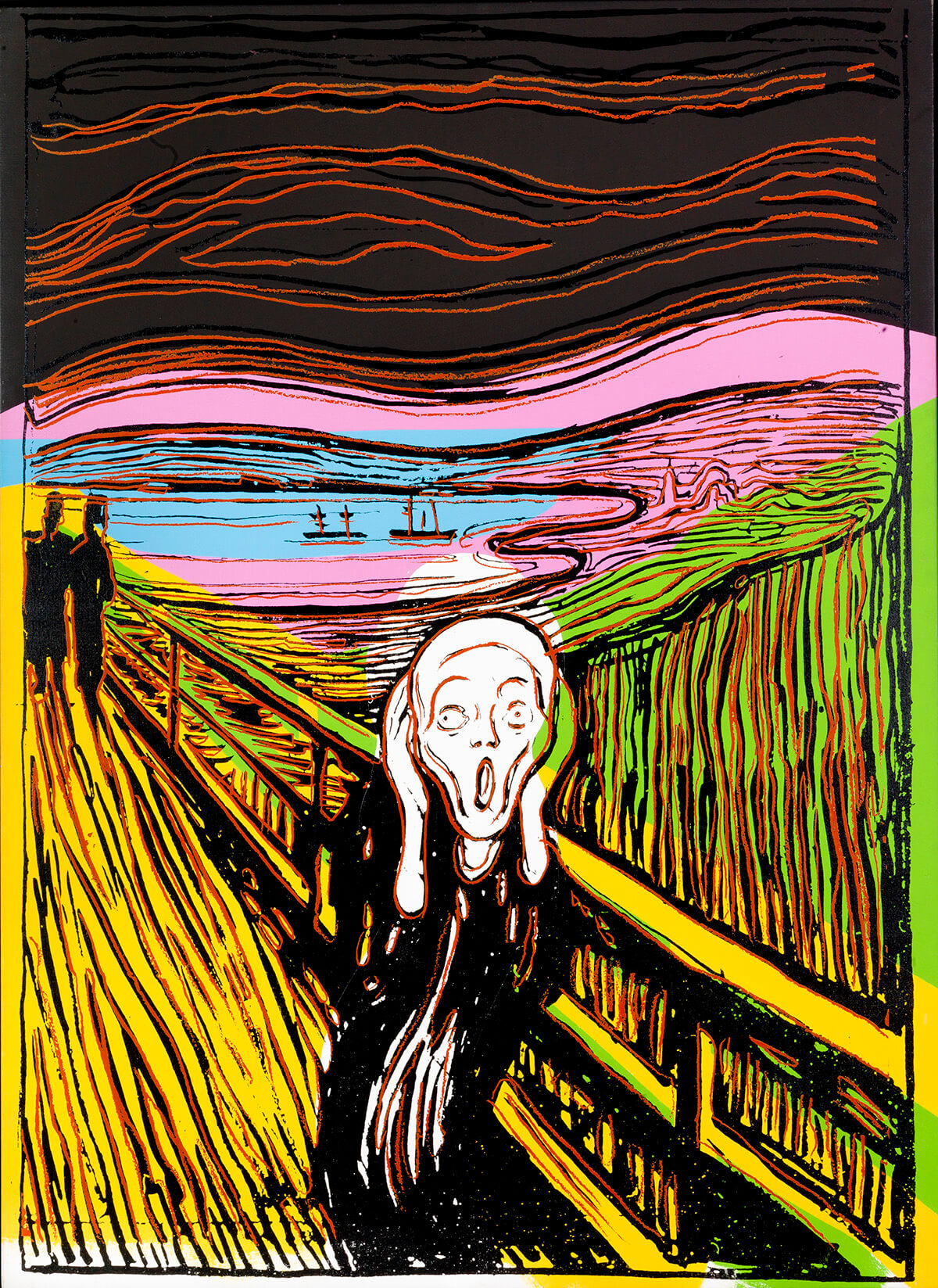

We also loaned paintings by Futura and Timothy Curtis to Art Science Museum in Singapore for an exhibition called Sneakertopia, which celebrated everything related to the rise of street culture and pop art, and the phenomena of sneaker culture.

Kim Lim at Hepworth: the first major museum exhibition of Lim’s work since 1999, offering unparalleled insight into the artist’s life and work.

Futura and Timothy Curtis at the Art Science Museum

Where has your acquisition strategy been particularly effective in nurturing innovative artists?

CHS: I like to support Singapore’s young and emerging artists. There is one artist in particular Hilmi Johandi whom I spotted almost fifteen years ago at the Affordable Art Fair in Singapore in 2011, today he is represented by OTA Fine Art, one of Japan’s leading contemporary art galleries who also represents Yayoi Kusama. I commissioned Hilmi to create a family portrait for us. Since then I support his practice by buying a work from every new series.

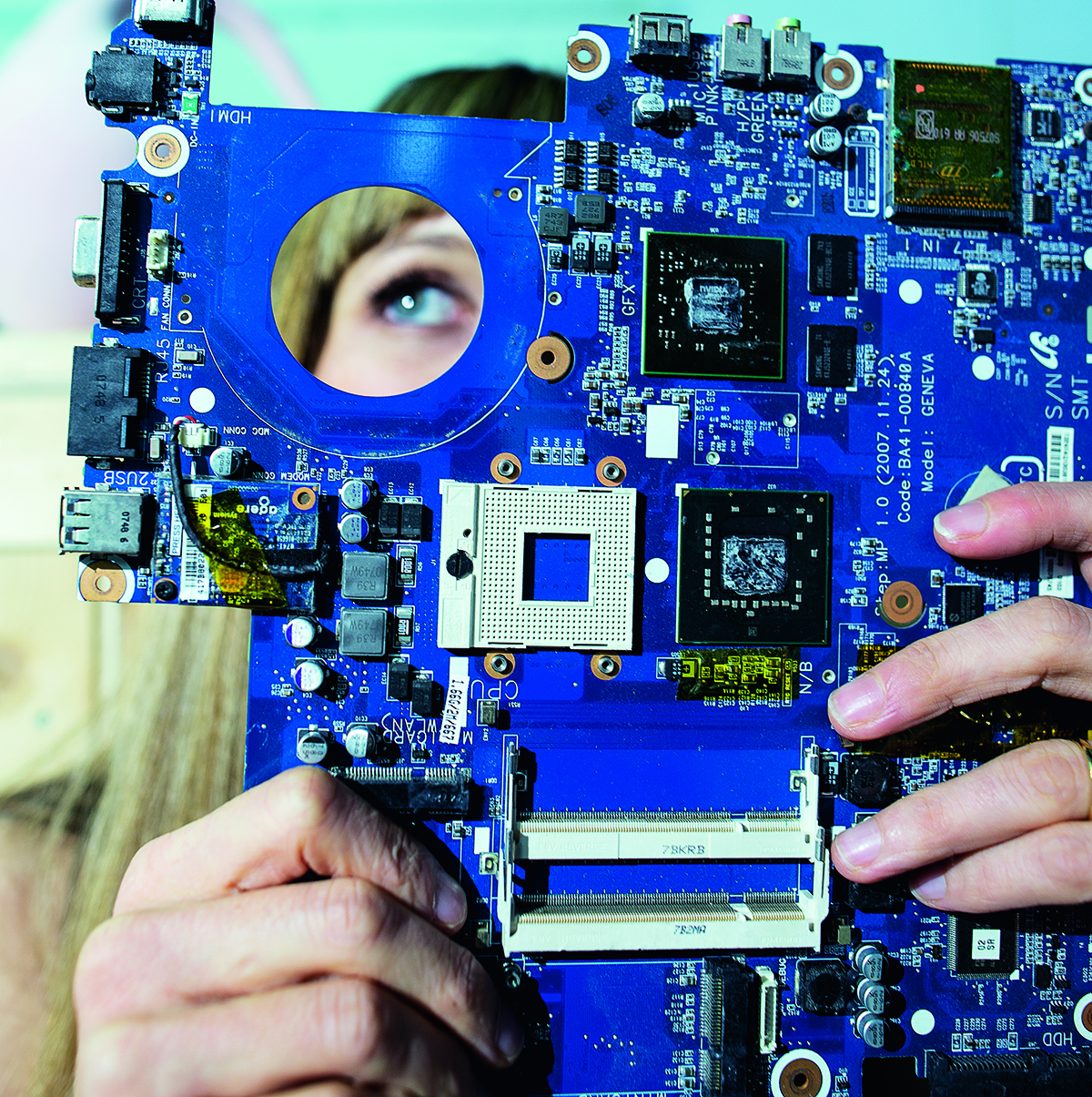

Hilmi Johandi works primarily with painting and explores interventions with new media that are associated within the domain of framing, fragmentation and compression

What is it about the Asian art market and intergenerational wealth transfer that created demand for the Family Office for Art (FOFA)?

NC: The South East Asian art market is still a young one, over the two decades we have seen significant progress with the emergence of galleries, art fairs, biennales, dealers and private museums etc.

Two years ago, I identified a gap in the industry, and I felt there were many things I could offer and help other collectors, the same way I used my skills and experience to maintain my father’s art collection. Most wealthy families have their financial assets and businesses handled by their private banker or family office, more often than not, the soft assets such as art and collectibles are overlooked or neglected. However these “passion assets” are very much part of the principle’s estate and his/her legacy. I’ve been studying this space for some time and I’ve learnt that with a proper system in place, it is a significant step towards protecting and enhancing the art collection’s commercial and cultural value.

At FOFA, we understand that dealing with passion assets such as art can be emotional and sentimental, and more often than not, it would require some degree of family involvement. These types of discussions and conversations are not unfamiliar to us and may take a long time to materialise, so our approach is to take a long term view and invest in these relationships.

Read more: Yulia Iosilzon’s groundbreaking new show in London

Based in Singapore, we are well-positioned to meet and serve Asian collectors in the region. Over the next decade and even in present times, it has been said that there will be unprecedented levels of wealth transfer in Asia. Given our first mover advantage and as we continue to grow and widen our international network, FOFA is ready to help families look after and manage their passions or alternative assets such as fine art and collectibles.

1. Of all the things you might collect, you chose ‘tat’. Why?

1. Of all the things you might collect, you chose ‘tat’. Why?

Recent Comments