The two Maranellos together (Photo: Laetitia Sanai)

The Ferrari 550 Maranello and its successor, the similar-but-different 575M Maranello, are becoming two of the most sought-after cars of the ‘modern classic’ era. Rakish two-seaters with V12 engines, they also divide opinion among collectors as to which of them is best. Now, 20 years after the 550 Maranello was first unveiled to rapturous reviews, LUX takes both of these beautifully svelte Ferraris out for some spirited driving and comes out with a surprisingly unequivocal answer.

There are few things more inspirational, to collectors of classic cars, than Ferraris hosting V12 engines. Any car person will become dreamy at the mention of a 275 GTB or Daytona from the 1960s; cars that combined race heritage with beauty and an engine whose functioning and sound is worthy of an installation at MOMA.

Ferrari still makes cars in this lineage, the latest being the 812 Superfast, an even faster successor to its F12 model, itself a car so rapid that to extend it and enjoy it you would, within a couple of seconds, be so in excess of a speed limit in almost every country in the world that you would be risking a jail sentence.

Like some of the proudest global dynasties, this V12 line had its reign rudely interrupted before being restored to the monarchy. In the 1970s, 80s, and early 90s, Ferrari instead made cars with a flat-V12 engine (a detail that refers to the arrangement of cylinders in relation to each other, important for car geeks), which was placed behind the driver and passenger; these included the famous Berlinetta Boxer and Testarossa, and the limited-edition, lightweight (and now highly collectible) F512M).

It was only in 1997 that the company continued where it left off with the Daytona of 1968, and replaced the F512M with the 550 Maranello, a car so different it shared only its available paint colours with its predecessor, and whose design – (new) V12 engine under a long bonnet in front, space for two people behind – resembled its deposed ancestor.

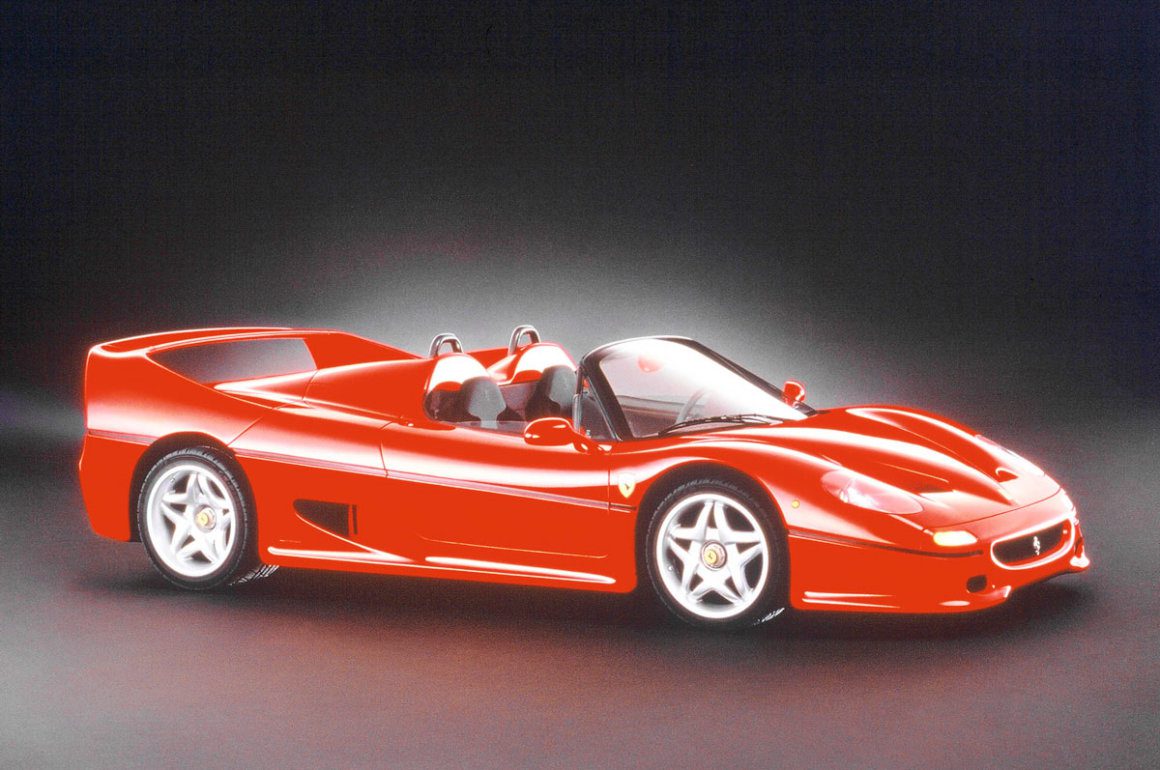

The 1997 Ferrari 550 Maranello, in classic Rosso Corsa (racing red)

The 550 was itself replaced by the 575M in 2002 which (pay attention at the back) was a modified version of the same car – an evolution not a revolution – and looked so similar from the outside that even experts have trouble telling them apart. (There were greater changes inside and under the bonnet, as outlined below). In 2006, the 575M was itself replaced by an all-new car, the 599 Fiorano, with a different V12, still under a long bonnet in front.

And – for those general readers still with us – this is the rub. The Maranellos, as the 550 and 575 were called, represented a singular era in Ferrari history. The cars that preceded them were, as outlined above, very different in every way; and their successors, the 599, F12 and today’s 812 Superfast, are also very different: faster, but also much more aggressive, with hair-trigger handling meaning they demand to be driven at high-speed all the time, and feel listless and a little dull if they are not.

The rare gated gearshift on the Ferrari 575M Maranello

The Maranellos, meanwhile, had a laid-back demeanour that fooled purchasers into thinking they were relaxed cruising cars – until they tried driving them at high speed, and realised they were every inch a thoroughbred Ferrari. This dual personality is unique among Ferraris, and the cars are now appreciating in value as connoisseurs recognise this.

To give additional spice to the collectability of these ‘modern classics’, the 550 was the last Ferrari to be made only featuring a metal gated manual gearshift. This may not sound significant, but every Ferrari made now is only available with a F1-style ‘paddleshift’, with no clutch pedal or gearlever; and so the beautiful metal gated gearshift has become a desirable element of many collectable Ferraris. The 575, meanwhile, was generally promoted with its F1-style gearshift, and of around 2000 examples made, only 246 were ‘proper’ old-fashioned manuals; and of these, only 69 were right hand drive examples for the UK, making them seriously collectable.

Read next: Why you should buy a modern classic car

Sibling rivalry

The 550 received rave reviews from the motoring media from the outset, appearing so much more modern and sophisticated than its F512M predecessor. (Ironically, it is the quirky design and single-minded racy focus of the rarer F512M, of which LUX also owns an example, that have made its value whiz upwards far beyond those of the also-appreciating Maranellos, in recent years). When the 575M came out in 2002, it received a more mixed reception. More powerful, with a bigger engine, extensive modifications underneath, and more luxurious inside, it was nonetheless criticised by some for being a little too comfortable and soft – not enough of a Ferrari. Critics and purchasers rapidly realised that the addition of the factory-optional ‘Fiorano Handling Pack’, aimed at racetrack driving, righted things for the 575, as did a series of Ferrari’s own subtle modifications over ensuing months.

Still, though, the reputational damage, slight though it was, was done. A cloud hung over the 575, based on the initial reviews of it being too ‘soft’. Supporters of the 575 ever since have claimed that this is entirely unfair, and that the 575 is newer, faster, better and, with the ‘Fiorano Pack’, also racier than the 550; while supporters of the 550 say the original car is better and that Ferrari’s modifications simply clouded what had been a perfect machine.

The debate is muddied further by the gearchange developments. A tiny minority of 575s were sold with gearlever manual transmissions similar to the 550s, meaning it was very hard to compare like-for-like: a typical 575 with F1 paddleshift transmission and no Fiorano Pack was a different beast indeed to a typical 550.

Solving the debate: 550 v 575M Manual Fiorano Handling Pack

LUX is fortunate enough to own a beautiful example of a 550 Maranello from 1997, and a 575M Maranello, manual, from 2004. Both were purchased for their collectability, and for the joy they should impart in driving. And this offers us an almost unique opportunity to resolve, without bias, the question once and for all: is a manual 575M Maranello, with the coveted Fiorano Handling Pack, a better car than a 550, or is it too close to call? We took both cars out this spring to find out. First, our criteria: this was not about which car was faster (the 575M should be, by dint of 30 extra horsepower and a bigger engine), or more fun around a track (we didn’t actually take them to a track, though we did create an approximation of one out of some empty roads – responsibly, of course). It’s about which is a better all round V12 Ferrari, with a combination of performance, presence, handling, comfort and general brilliance.

The 550 Maranello

We purchased our 550 Maranello in its homeland, a couple of years ago. Prices had started to rise, and we were on the lookout for an excellent example of this model. A very low mileage example popped up on an Italian car website and, acting fast, we flew over and purchased it, as documented here in GQ magazine. The car had been kept in a showroom for ten years, and needed some fettling, admirably carried out back in the UK by The Ferrari Centre in Kent, to go as well as its museum-piece looks suggested.

The 550 Maranello’s “gills” hark back to Ferrari’s supercars of the 1960s

The shape of the 550 was a stark contrast to that of its predecessors when it came out; in retrospect, like the greatest designs, it was ahead of its time with its understated angles, and the harbinger of a new era. While it’s not as beautiful as the most gorgeous Ferraris, it has aged beautifully and now gains the attention that, ironically, it didn’t do when it was new. Slim, svelte, sleek and minimal, it feels very grown up.

Drive the 550 down a busy highway and the initial feeling is…what is all the fuss about? The engine is quiet – so quiet, nobody takes note of it, so much quieter than almost every other Ferrari, that you feel a little short-changed. This is a near-legendary Ferrari, but in a quiet way.

Read next: The nostalgic pleasures of travelling by ferry

The car also doesn’t immediately speak to you through the steering wheel as you might expect it to. The power steering is light and easy, but rather over-light; when it was created, the emphasis was on creating a Ferrari that could be used every day, and the tradeoff now is that ease-of-use and refinement seems to trump sense of occasion. Only the bang, clang from the metal gearshifter gate tells you you are in something special.

The 550 has a more ‘classic’ interior layout

Out on the open road, though, things change, fast. Push the accelerator and the engine roars as it whisks into the upper end of its operating range; the car flies forward. Most wonderful is the way it goes around corners. It flows and flies through fast corners, and on tighter ones, encourages you to go ever faster. As you stretch it, it wakes up completely from its straight-line stupor, and surprises you utterly: the 550 comes alive, progressively communicating more as it careers around tight corners. Drive harder and it gets happier, fluidly and consistently letting you know where you are in its considerable range of abilities, encouraging you to steer around bends with the accelerator, faster, faster, tighter, pushing it around and out.

And then there is the most wonderful moment of all: when you are flying out of a curve and accelerating ever more, you have a sensation that the momentum is about to be with the back wheels, and not the front wheels. It’s as if the car has been created to tap you on the shoulder and say, ‘Ciao. In a second, my rear wheels will start to slide, so, let’s have fun, ragazzo!’. Then they do so, and you flick the steering wheel and catch them, and tear on down the road.

All of this from a car that looks and feels, at low speeds, like a gentle cruiser. Spectacular.

Driving back to base, that feeling of a lack of feeling comes back again, though. At lower speeds the 550 is so quietly competent that it makes you a little restless. And while it feels very modern in many ways, it shows its age in the background noise generated by the body while travelling at speed on the highway.

The 575M Maranello Manual

The 575 has its rev counter centred

Sit inside the 575 and, unlike the view from outside, the contrast with the 550 is immediate. The dashboard is updated: the 550 has three dials at eye level towards the centre, while in the 575 your view is dominated by a big rev counter. The leather and materials are of a higher standard, and the whole experience feels more luxurious, while distinctly similar.

Anyone expecting Ferrari to have upgraded the aural experience – the only real criticism of these cars – would be disappointed, as the 575 is as quiet as the 550 at slow speeds. I felt myself yearning for a V12 howl, rather than the smooth hiss of the engine in front; but the 575 is almost indistinguishable from the 550 in this way. It’s a very understated car.

In other matters, though, considerable progress is evident. The most prominent of which is the steering: it has far better weight, and more feel, than that of its sibling. While it doesn’t communicate like Ferraris did before power steering, it gives you a firm, meaty sense of exactly where the front wheels are pointing and what they are coming into contact with. This improved steering was part of the Fiorano Handling Package. The accelerator also has a more immediate response; meanwhile the gearchange is similarly satisfying. I tried to find a difference between these two delicious metal gated gearboxes, and if pushed I would say the 575 feels even more metallic and mechanical, but that’s probably quite moot.

The 575’s handling is also quite different. With the Fiorano Pack, aimed, according to Ferrari, at racetrack driving, I expected it to be altogether harder and stiffer than the 550, but that’s not quite the case. The first impression is completely the opposite. At very low speeds, over a speed hump, for example, the 575 has a slight but distinct return on its springs: where the 550 goes up over the hump and down, the 575 goes up, down, bounces back up again almost imperceptibly, and settles. One tiny extra movement. (All the Fiorano Pack 575s I have driven do this; and it’s not something you notice until you drive it alongside the 550.)

On the road, in a corner, this translates into a slight but definite bit of lean into a bend, then, as if the system is flexing its muscles, the ride turns flat and the car gets stiffer as you corner harder, both into and out of the corner. The 550, by contrast, felt simpler and more fluid.

At higher speeds through corners, the 575 is flatter, stiffer, and feels stronger than the 550, but if you are linking together a series of S bends, the 550 feels like it is making less effort – in a good way. It almost feels lighter, which it isn’t.

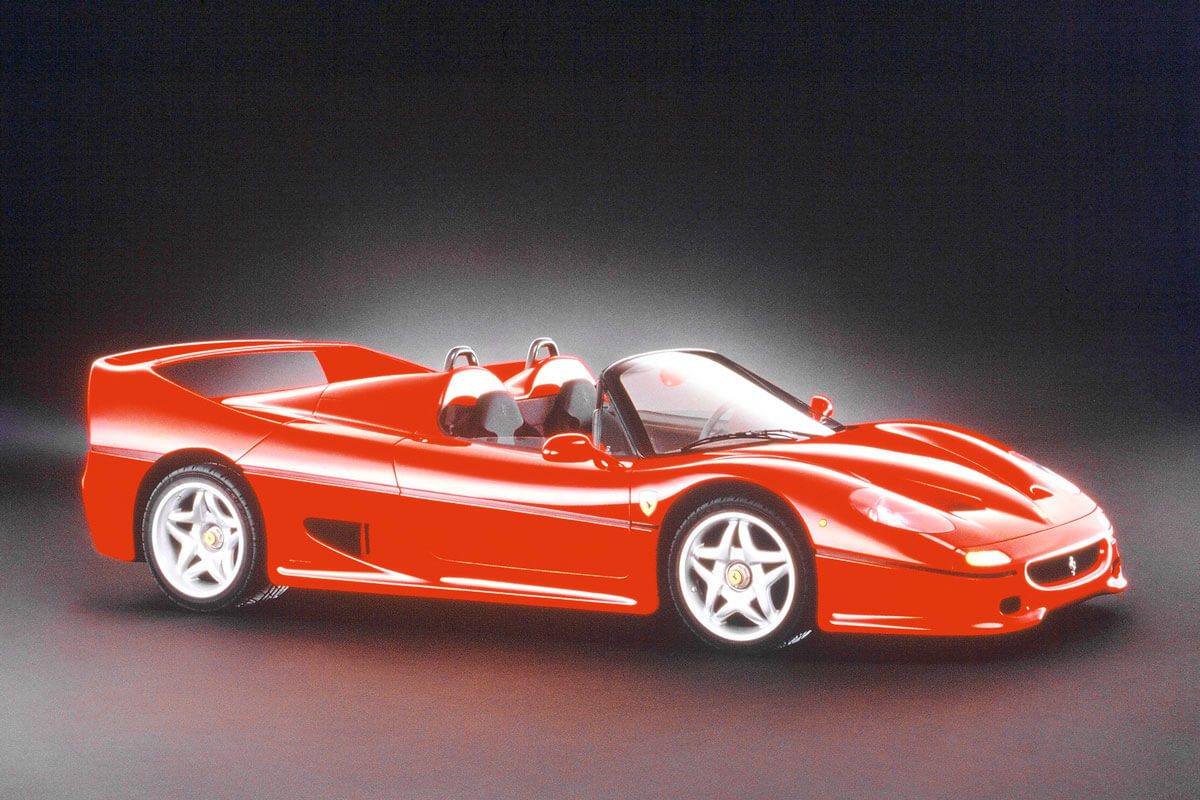

The 2004 Ferrari 575M Maranello was an evolution – but was it an improvement?

Push harder, and the 575 sticks to the road better than the 550; it leans less at the limit. It’s also noticeably faster, as you make the engine fly: those 30 extra horses, and the extra 250cc of engine capacity, really are noticeable. It makes for a car that is both speedier and more satisfying than the 550 to drive at medium-high speeds, although if you are in a situation where you are making the rear wheels drift out of a corner, the 550 can be caught more cleanly, and feels more simple and playful.

Read next: Super chef, Massimo Bottura on his food for soul project

On a long drive, more advantages of the 575 become clear. It rides better, even with the Fiorano Pack, and the body creates less background noise. It feels more settled than the 550, more sophisticated. It’s really the steering, though, that is the killer winning factor: whether cruising down a straight highway or into a series of curves, the excellent weight and good feel of the 575’s Fiorano Handling Package steering make it a satisfying, involving machine to drive, at times when the 550 feels like it is half asleep.

The Winner

Red brake calipers can denote racing suspension pack

We thought this would be a difficult, entirely subjective battle. But in the end, the 575’s one significant advantage over the 550 – the steering – plus the numerous small improvements in performance, ride, refinement, interior quality and sophistication, cancel out the 550’s trump card, its joy at the limits of handling. If you are buying a car to drive at its limits every day, then perhaps this trump card would be the killer app to swing your modern classic decision towards the 550. We also think that, from the outside, the 550 looks just a little cleaner and better. But overall, as a Ferrari for fast, real-world driving, combining speed, luxury, handling, refinement and utter aristo-Italian factor, the 575M manual with Fiorano Handling Pack beats the 550, and by a quite distinct margin. With only 69 made like ours, it’s also a true modern classic.

FOOTNOTE: Party Pooper?

The Maranellos were succeeded by the 599 Fiorano, which sported a massive increase in power and technology; it heralded a new type of hyperactive V12 from Ferrari. The 599 itself was replaced by the F12, much more powerful, lighter, more agile and much faster again.

But the predecessor to the Maranellos was such a different type of car, never to be made again by Ferrari, that it has gained a cult following and commands roughly twice the price of a 550 in the classic car market. The F512M (LUX owns one) was a two-seater with a lightweight 12 cylinder engine behind the driver’s head and a modified body from the legendary Testarossa. Impractical and loud (in every way), it was also much lighter than the Maranellos, to the extent that Ferrari itself admitted the F512M had better acceleration than the 550 that replaced it.

It also has the sense of occasion of an Italian countess arriving at a Roman ball. Every minute spent in a F512M is memorable, you can feel the machinery all around you, as well as the stares of passersby. It’s also wildly exciting on a twisty road, until a point, easily reached, when it’s just wild. The Maranellos are far better cars, but for sheer presence and occasion, their predecessor still has what it takes.

Acknowledgements:

No serious collector of investments of passion, be they mechanical watches or modern classic cars, can be so without the wise counsel of trusted professionals in the field. For the 575M Maranello, LUX would like to thank Joe Macari whose unrivalled knowledge and nous makes up London’s greatest Ferrari dealer and service specialist: Macari takes as much care over the service of a modern classic as he does over the restoration of a £10m unique classic.

The 550 Maranello resides in the hands of The Ferrari Centre in Kent, south of London whose owners, Roger and Claire Collingwood, are both ex-racing drivers and mechanics with a deep understanding of the cars and the market: they both own modern classic Ferraris as their everyday cars.

Anyone researching or owning a Maranello will find the Ferrarichat board an invaluable resource; technicians, owners, dealers and others offer fellow members a formidable knowledge-bank.

Passion is the essential element for an investment of passion, and we share just a little bit of all of theirs.

Recent Comments