The conversation between Durjoy Rahman and Sam Dalrymple took place over Zoom. We have used artistic licence to create the photo montage above

In the third of our series of online dialogues, Sam Dalrymple, Activist and Co-Founder of Project Dastaan, speaks with philanthropist Durjoy Rahman about cultural reconnections post-partition, the importance of multi-cultural artists across borders, and the rapid shift in popularity away from the West and towards the East. With an introduction and moderation by Darius Sanai and created in association with the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation.

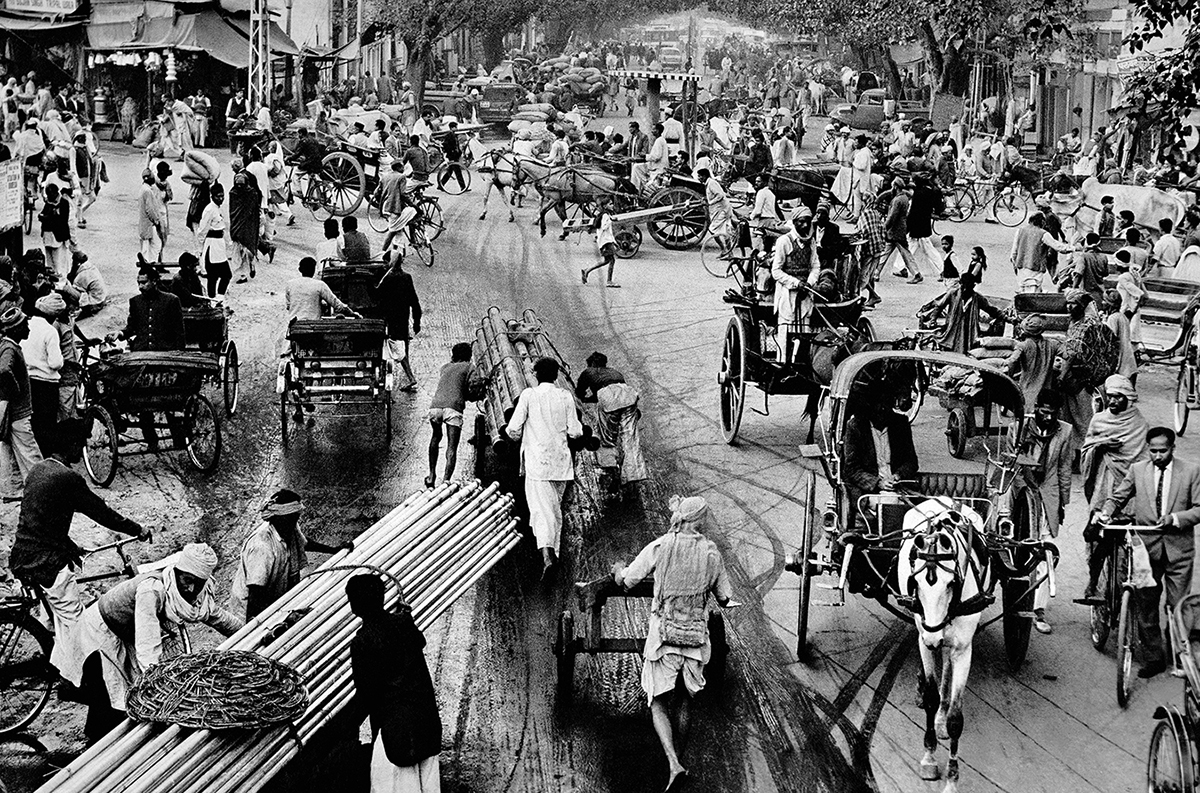

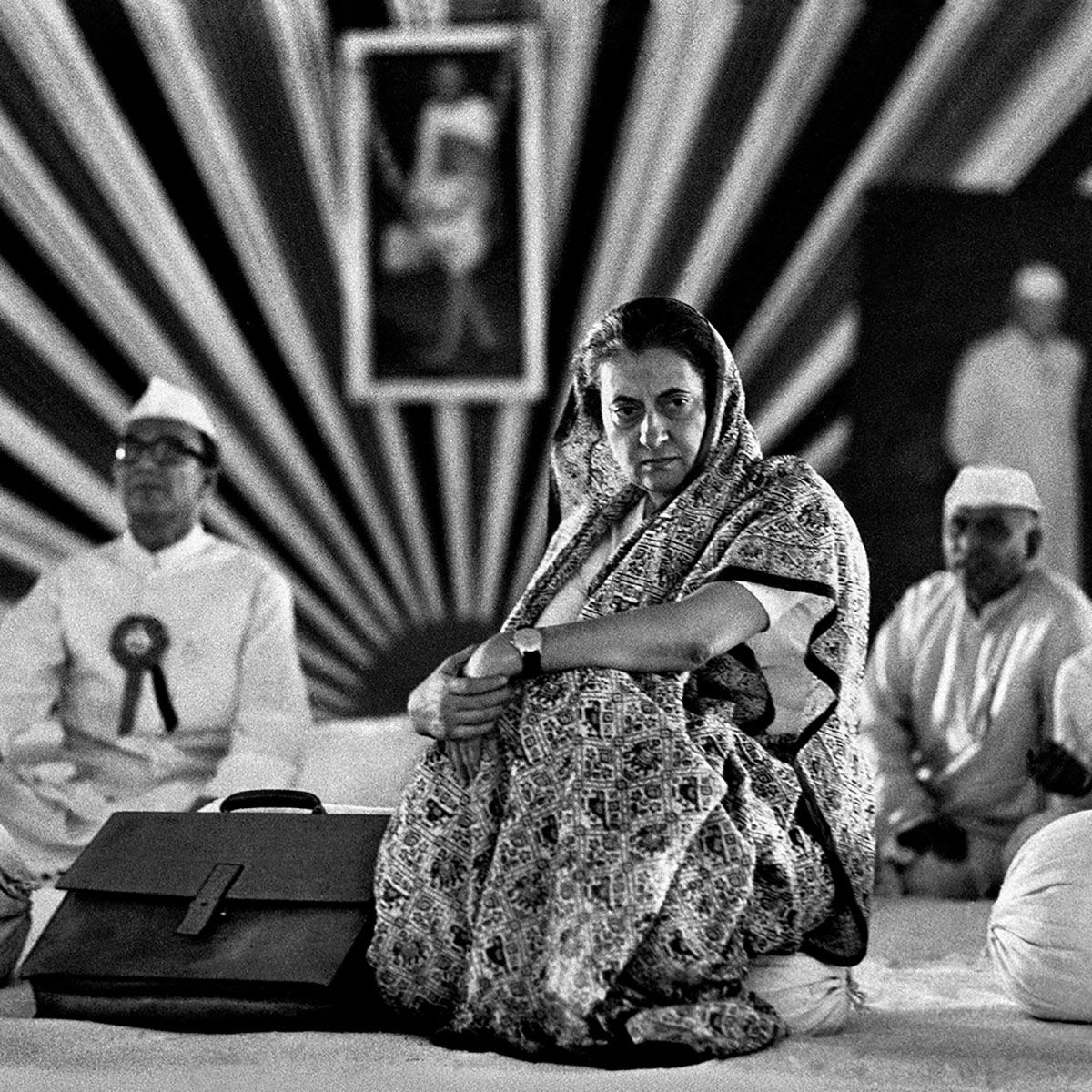

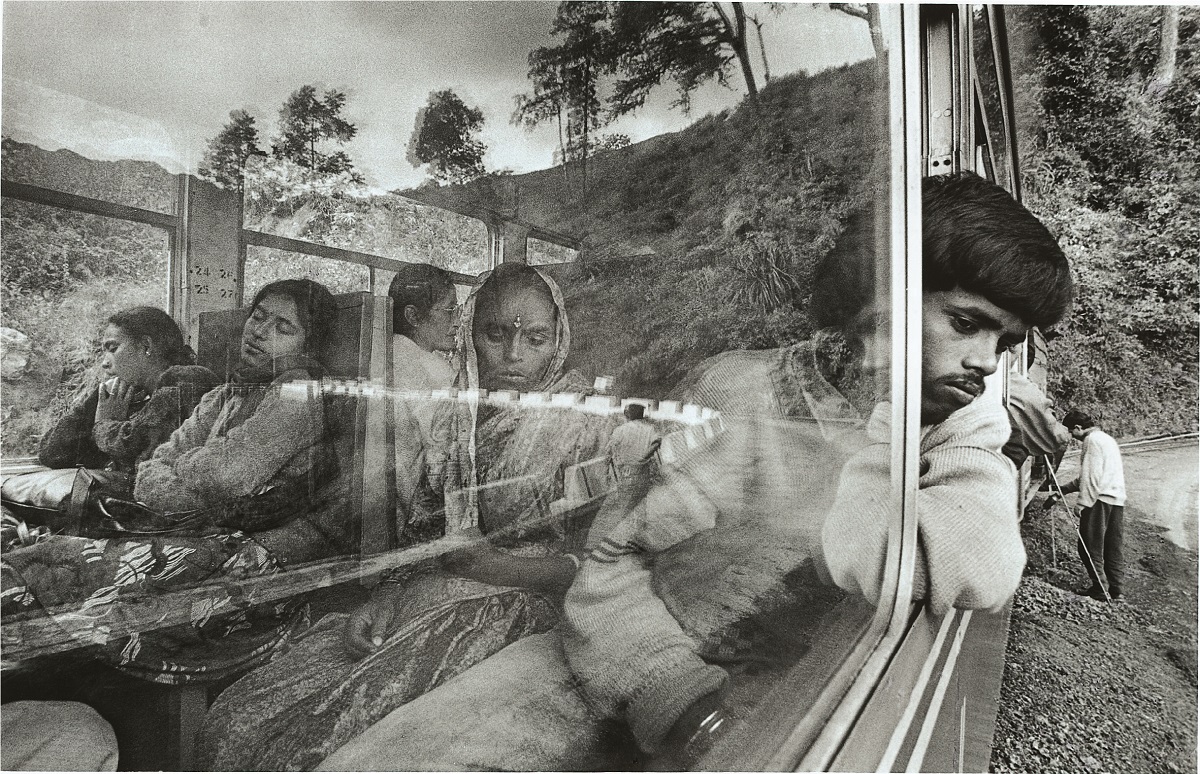

Raghu Rai is a Magnum Photographer who chronicled the Independence war of Bangladesh in 1971 when the territory that was East Pakistan gained independence from what is now Pakistan. The Indian army ultimately came to the aid of Bangladesh after an enormous refugee crisis ensued. We present a selection of his works within this article

LUX: Sam, could you tell us firstly what sparked your interest in Partition and inspired you to create the ground-breaking ‘Project Dastaan’?

Sam Dalrymple: Project Dastaan began when my friends Sparsh, Ameenah and Saadia were at University chatting about the fact that everyone’s grandparents had migrated from somewhere in the Sub-Continent, and how bizarre it was that in the UK you could have the easiest conversations about this.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

When you are in India, it is difficult to chat to a Pakistani, when you’re in Pakistan it’s difficult to chat to a Bangladeshi as these walls have been built up in the Sub-Continent, so that it is actually in the former colonial power where it is easiest to talk.

There were conversations about how Sparsh’s grandfather had migrated from near Islamabad, in Pakistan, and here was Saadia who was from near there and could easily go and take pictures of his old house or temple which had been impossible for Sparsh’s family for 75 years. They had no pictures of it, no idea where they were from. The ease from a London standpoint to re-connect triggered the whole thing.

Ayodhya, india 1993

The partition that is the cause of this fragmentation in India was, simply put, the largest forced migration in human history. In the course of a year what had been British India, was divided into two territories, which is now three – India and Pakistan, which later became Pakistan and Bangladesh. This was 75 years ago and for most of that time, most of the migrated people have never been able to see their homes again.

So it began as an attempt to use virtual reality to re-connect Partition survivors across borders, so if you came from Lahore and had migrated to Delhi, we would go out and find your old Mosque, your old school, your old house and, if we can, find any friends who you knew before 1947.

Chawri Bazar, old Delhi, India, 1972

We additionally wanted to translate some of these stories that we were hearing, into animations with a cross-border, collaborative studio in Bangalore and Lahore, which was in itself an attempt at cross-border with team members scattered from Bengal to Punjab. Then, we finally made a film called ‘Child of Empire’, which just premiered at Sundance. It is a VR mini-movie, a 15-minute animated journey through the Partition based on Sparsh’s grandfather’s story and another man who did the opposite journey. It is about these two men 75 years later chatting to one another and the therapeutic discussion of their two journeys which mirror each other in so many ways but, obviously, have been polarised so much over time.

LUX: In the context of Partition, what does Partition and its consequences mean to you Durjoy?

Durjoy Rahman: I come from a generation where it was my parents who had seen the displacement, twice. They were born during this time and have seen the consequences and the aftermath of partitions first hand. I grew up hearing everything that happened in 1947, the riots and so on. So between me and my parents we have seen the largest displacement in the history of these civilisations that happened in this region. These experiences have influenced me to do activities surrounding Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation heavily.

Mother Teresa at her refuge of the Missionaries of Charity in Calcutta, during prayer, India, 1979

LUX: Do people have a strong sense of national identity currently? Would you say that this is down to cultural or religious differences?

SD: It is many differences and culture definitely plays into it. I think the memories of both ’47 and ’71 play into how people remember their pasts, but it is also a generational factor. The national identities are harder for the younger generation who never knew the other side of the border, whereas for a lot of people who migrated at the time nationalism was firing up these independence movements.

Art definitely plays into how we create a nation, with national anthems and the flag which of course crystalise these ideas of nationhood. What we’re seeing now is the crystallising of losing the generation who knew undivided India as undivided.

Imambara, Lucknow, India, 1990

DR: Nationality has always been an important element in the subcontinent. We always talk about India and Pakistan, but I would also include Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan in this context. Everyone holds their own nationalistic value to identify themselves and where they are from. But culture and religion, these two determined factors were also a factor when the British divided the subcontinent with the Muslims in Pakistan and left India where it was. A lot of people said ‘well, religiously you are all the same’ but religion is not the only deciding factor. We were culturally different so that was also important.

We are Bengali as Sam just said – we were never Pakistani, maybe we were all Muslims, but we were culturally different. So culture is a very important factor in defining borders and nationality. How you possess your cultural identity, this is what I believe defines you, and no matter how younger generations perceive themselves as a global citizen with a global identity, the identity borders will remain in our lifetime.

Indira Gandhi at a Congress session, Delhi 1967

LUX: Sam, Project Dastaan is ultimately a unifying project taking people virtually across borders. How has it been received among the people you deal with?

SD: It has touched people because it was something they thought was impossible, to see their old homes. The key thing has been not trying to look at the big and complex questions of Partition – We’re trying to show conflict through the eyes of an 8-year-old child. The generation that is still alive were mostly 12 or younger 75 years ago. We’re trying to show it through the eyes of the generation who’s still around. One of the things they would want to see is their old playground, their old houses, and the things that everyone can relate to. I think addressing the conflict and the great divide through these memories and nostalgia can be very healing.

Darjeeling Himalayan Railway (the Toy train), India, 1995

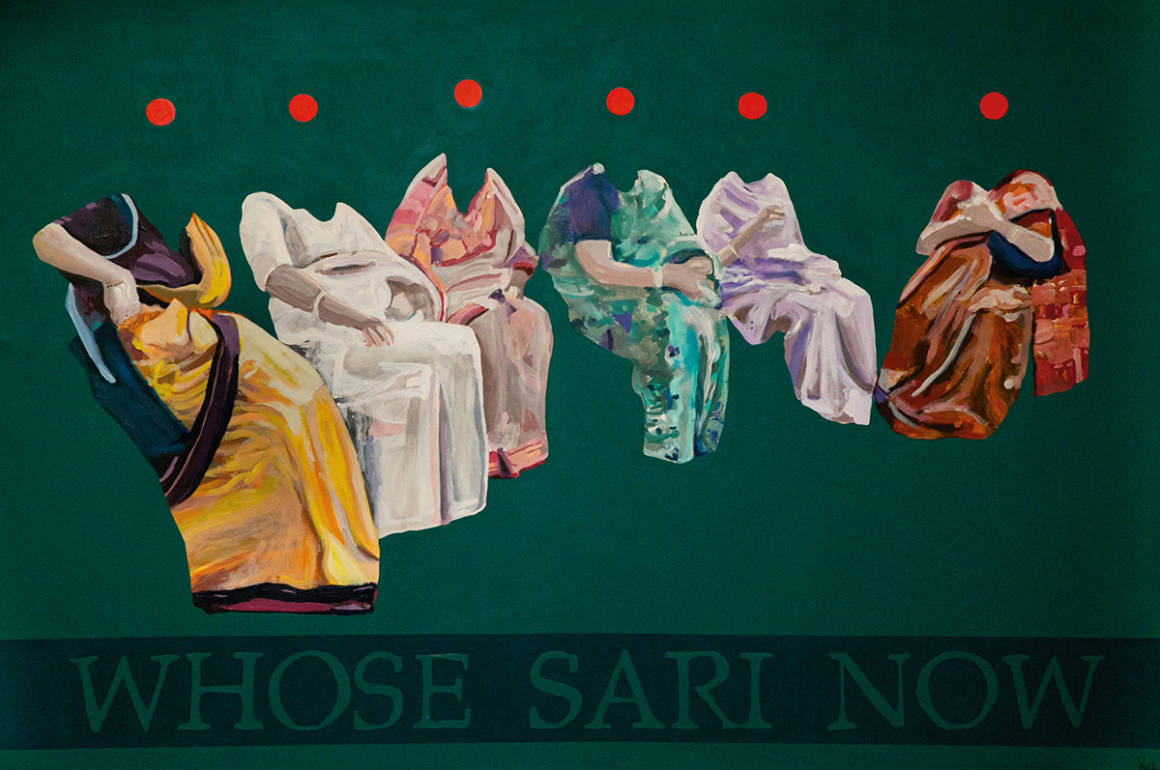

LUX: Durjoy, you wish to promote the art of people who may not have had a voice, without borders. How does that relate to the very definite borders in Pakistan, Bangladesh and India?

DR: Since DBF was established in 2018, our projects have been based on the concept of art without borders. We never considered ourselves a foundation that had originated from Bangladesh. We started working with creative personalities regardless of whether they were visual artists, musicians, literature backgrounds, performance artists and we did not consider which region they are from. We have always identified if their practice relates to the mandates that we are trying to highlight; displacement, disadvantage, ethnicity, some kind of challenge which probably obstructs their creative development. So, art without borders was our primary goal.

Woman pushing cart Delhi 1979

LUX: Sam, with Project Dastaan, what will make you feel like you have achieved your aim, what will you be doing in 5 years, 10 years?

SD: Who knows, is the answer! The big thing we’ve been working on is this particular year as it’s the 75th anniversary, and I think the aim has always been to raise awareness about what happened – the aim has always been to try and get people to record these stories, because they are disappearing rapidly. The foundation of our project has been oral history, and the contemporaneous generation is rapidly disappearing. I think we also have a particular aim within Britain, to get Britain aware of its role in the events.

LUX: Regarding artists and the film-making that you employ, was that something that you had conceived from the start that is not just a means of storytelling, but something that you want to focus on and encourage?

SD: With Project Dastaan, the aim has always been cross-border collaboration. For our animation teams, one of our animators had a family who fought in 71, another family was part of the trading diaspora across the Bay of Bengal. I think one of the interesting things is, and I’m not sure how deliberate it was, but the types of animators and the team we built around ourselves, seems to have brought in people whose stories kind of corroborate the stories we are telling.

Hand building highway – Hydrabad, India, 2004

LUX: Durjoy, with regard to the next generation that you’re supporting in terms of art and culture, do you feel that there’s a role for creative practitioners to break down these borders?

DR: I would say that I am not only very hopeful, but I am very optimistic. In this post-covid scenario, in this globalised atmosphere, I personally believe that we were in the right moment where we could take the entire South Asian art movement to the next level. Now the West has started looking at the East. Of course, our foundation and activities focus on promoting artists from South Asia, but we have seen a massive global increase in interest for South Asian artists. I also believe that these artists will take great advantage from the rising virtual scene within the context of the more active online and digital art scene within the past two years.

SD: I think what you said then is exactly right. One of the most interesting pieces that I’ve read recently was by Fatima Bhutto in her book ‘New Kings of the World’, which talks about the shift in the past 20 years. The biggest film industry is Bollywood, the biggest TV industry is Turkey now and the biggest music industry is now South Korea K-Pop. I think there is a lot of hope and a lot of growth in the artistic sphere here. I don’t think that will necessarily mean the borders themselves disappear; I don’t think that’s going to happen. I think there’s going to be more collaboration, more interesting art pieces and more embracing of technology for it.

Local commuters at Church Gate railway station. Mumbai, 1995

DR: Would you ever choose another region as your beaming point, other than India?

SD: I think the idea of virtual reconnections is something that you can use in an array of different countries, but we are so focused on areas affected by the Partition as that is where the personal connections of the team lie and a very specific area of interest where we can enact real memory connecting change. What’s unusual is that these countries are so close in so many ways, it’s just that trauma etc has left them severed from one another It’s a bizarre, specific situation that neither of them have ability for tourist visas, there’s no tourist visas for India and Pakistan, you can’t just visit, you have to have a reason and government approval.

Read more: Rana Begum and Durjoy Rahman on South Asian art’s global ascendancy

LUX: Possibly controversial, but I would love to hear from you both, what do you consider needs to happen for conceptions to really change around the Partition and affect the vast majority of the population?

DR: We have to perform what we believe and have to do what is good for the community, what is good for the region, despite what the supremacy wants to establish.

SD: I don’t think there is a simple solution, but I think that creating conversations and conflict resolution is always a noble aim. I think conflict resolution and actually talking about it is where to start, without bias and actually listening.

All images © Raghu Rai

Find out more:

durjoybangladeshfoundation.org

Recent Comments