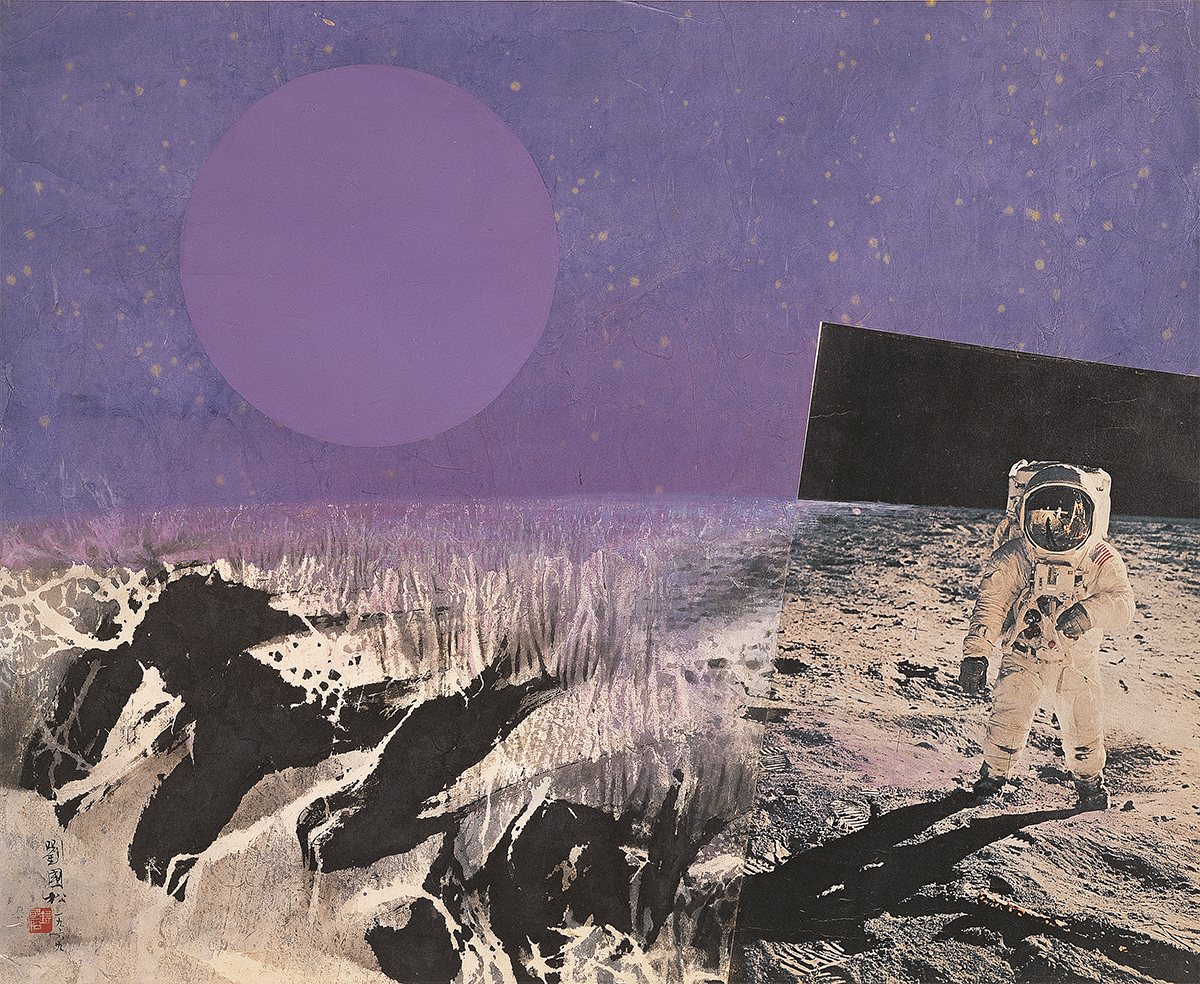

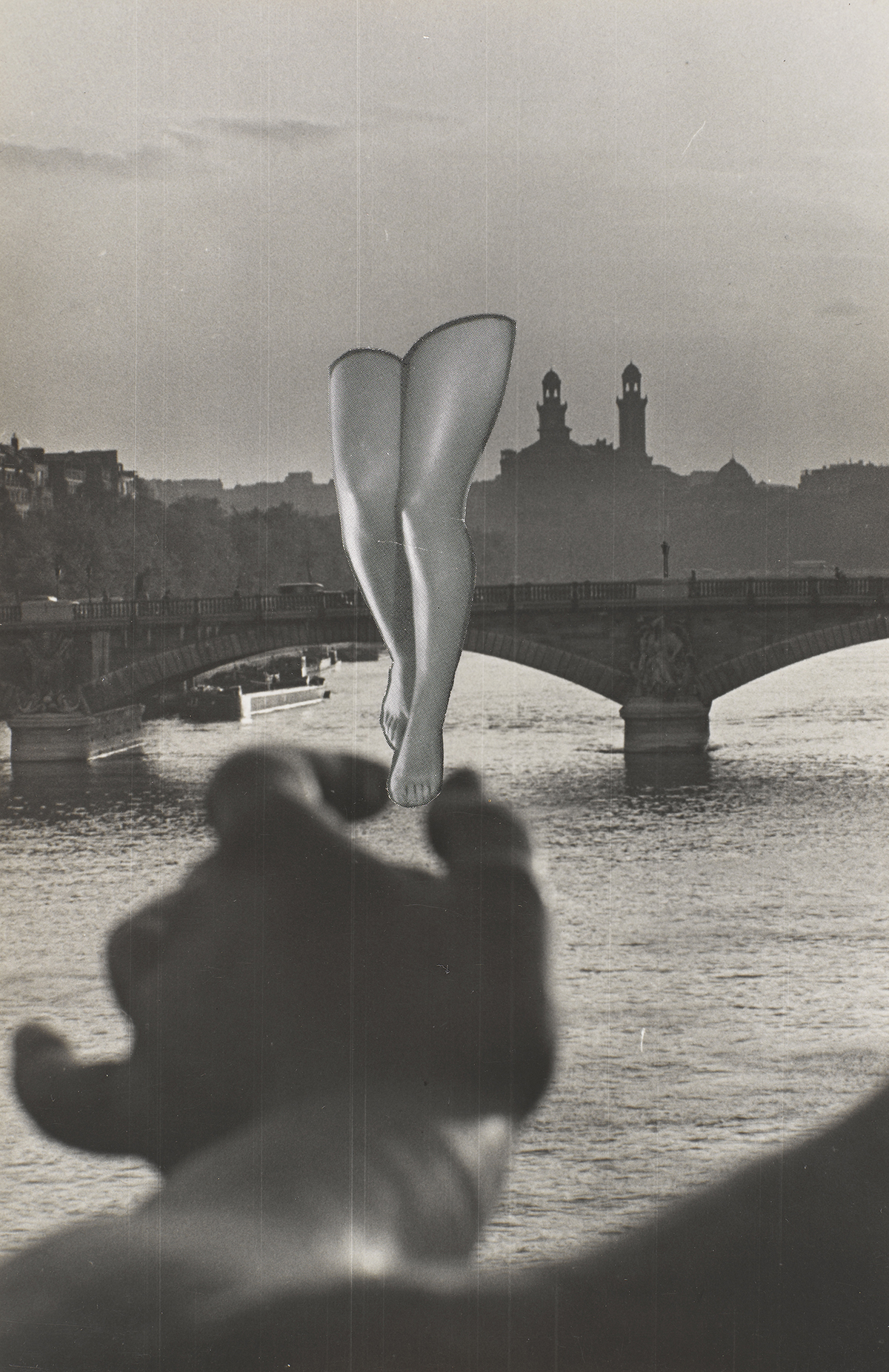

‘Moon Walk’ (1969), by Liu Kuo-sung

Navigating the deep waters of the Asian art scene could be treacherous, without a guide such as Calvin Hui. Jason Chung Tang Yen talks to the Hong Kong and London-based globetrotter, art connoisseur and entrepreneur about his mission to bring contemporary Chinese ink art to the global stage

DEUTSCHE BANK WEALTH MANAGEMENT x LUX

“Ink is not just a medium; it embodies a cultural language,” says gallery owner and art fair entrepreneur Calvin Hui. He’s referring to contemporary Chinese ink art and the enterprise he founded, a booming art platform titled Ink Now, first launched in Taipei and generating considerable buzz among art lovers and collectors. However, Hui’s vision for Ink Now extends beyond any fixed formats; he has introduced a notion of “more than ink, and more than an art fair. We are bringing awareness of ink art’s essence and spirituality in a cultural context, beyond its pure medium form,” he says.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

For more than 2,000 years, ink art, once made with burnt pine trees and organic matter on rice paper or silk, has been the primary – and most celebrated – form of artistic expression for Chinese calligraphers and painters. The traditional art form reached its peak in the Song Dynasty, from 960-1279AD; historical masterpieces from that era are still preserved in the palace museums in Beijing and Taipei and Qu Ding’s Summer Mountains has a permanent home at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Western artists, from the Impressionists to Pablo Picasso, have long been inspired by the ink art tradition, but in recent years, new media and influences from the West have made their own mark on the medium. Today’s artists often turn to or reinterpret traditional ink art techniques while in pursuit of a contemporary breakthrough, resulting in multi-layered works that are filled with cultural references and meaning. And some advocates for the medium, such as Calvin Hui, are hoping to lay the foundations for a new golden age of ink art.

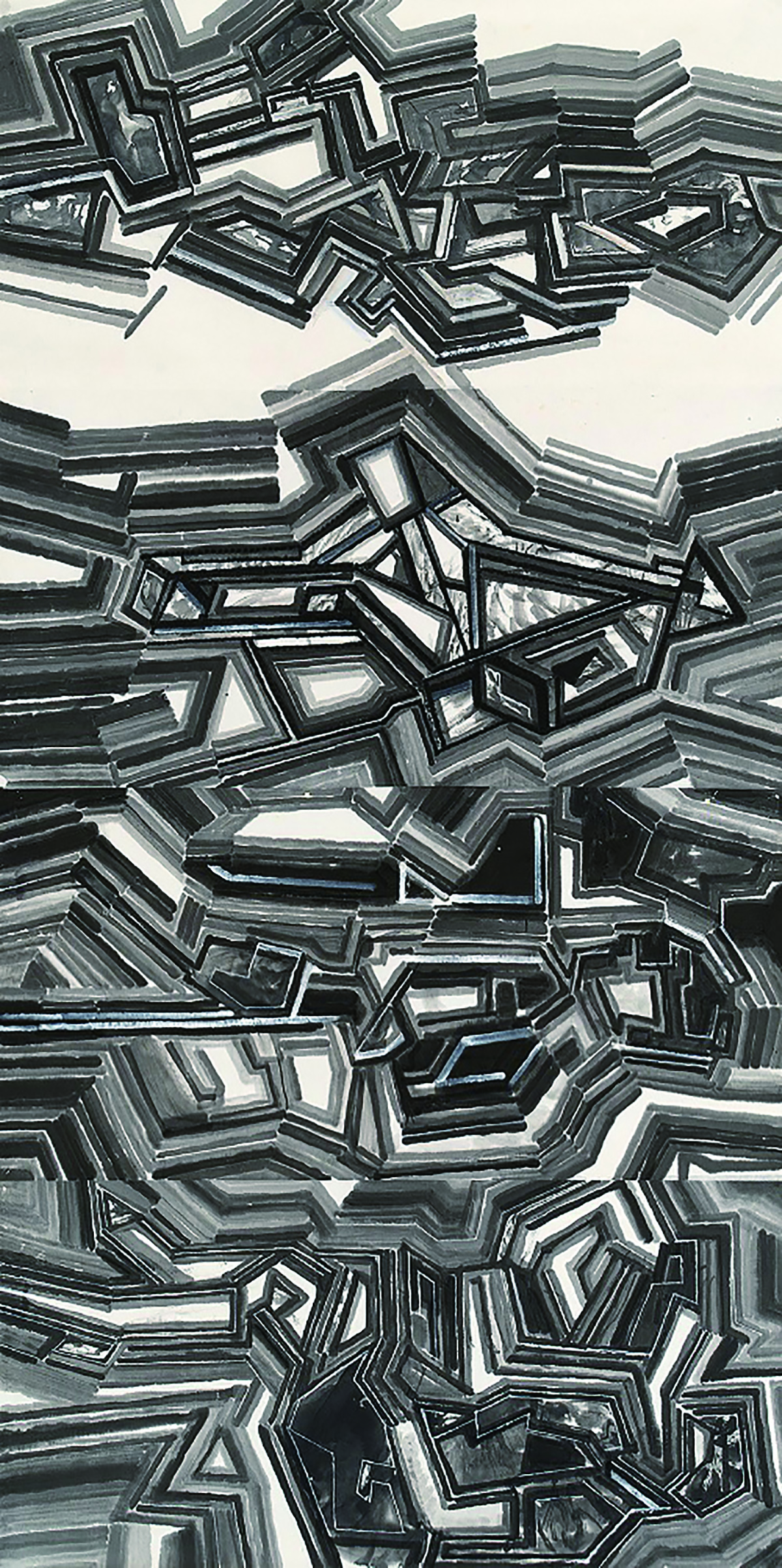

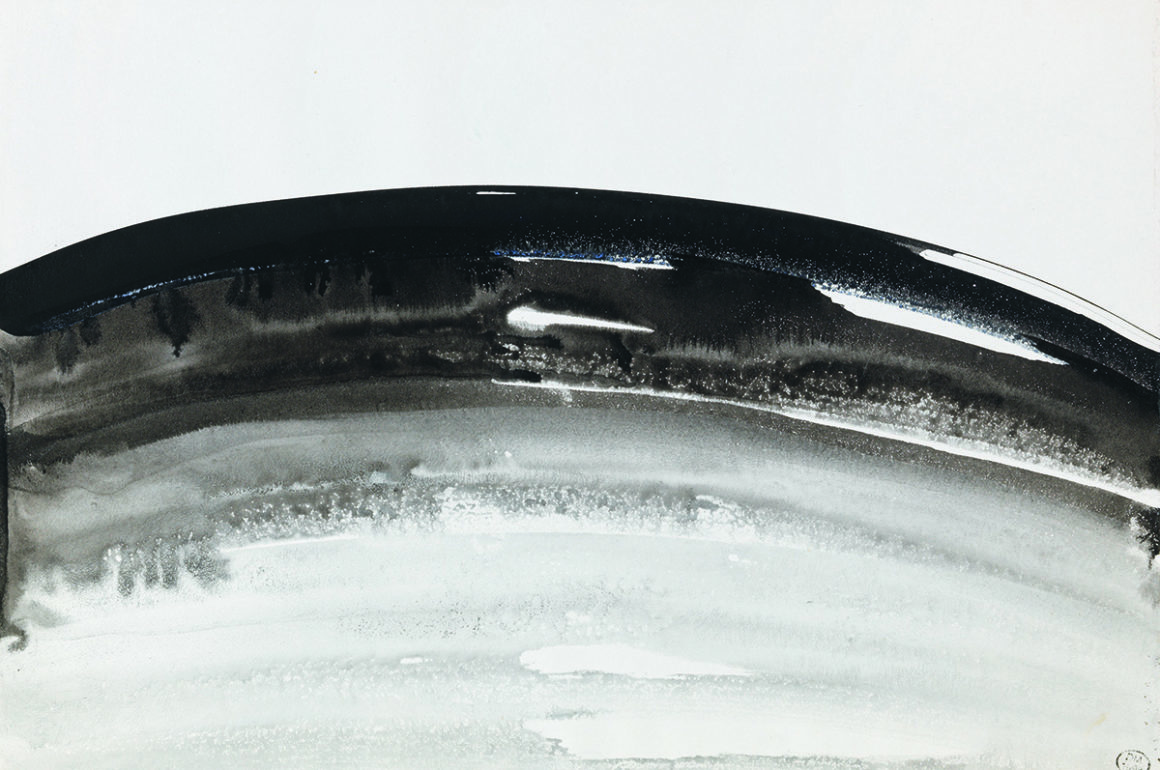

‘Far Side of the Moon’ (2019), by Victor Wong.

Calvin Hui at Victor Wong’s solo exhibition ‘TECH-iNK Garden’

A network of contacts and the ability to plan on a grand scale are required to make this happen, but Hui has long operated in the nerve centre of the art market, bridging the gap between contemporary Eastern art and the market in the West. He is the cofounder of the 3812 Gallery, with an outpost in Central Hong Kong and St James’s in London, and his company also provides professional and private art consultancy services. His vision for the Ink Now venture is driven by his passion for Chinese artists who are producing works steeped in heritage, but who look towards the future.

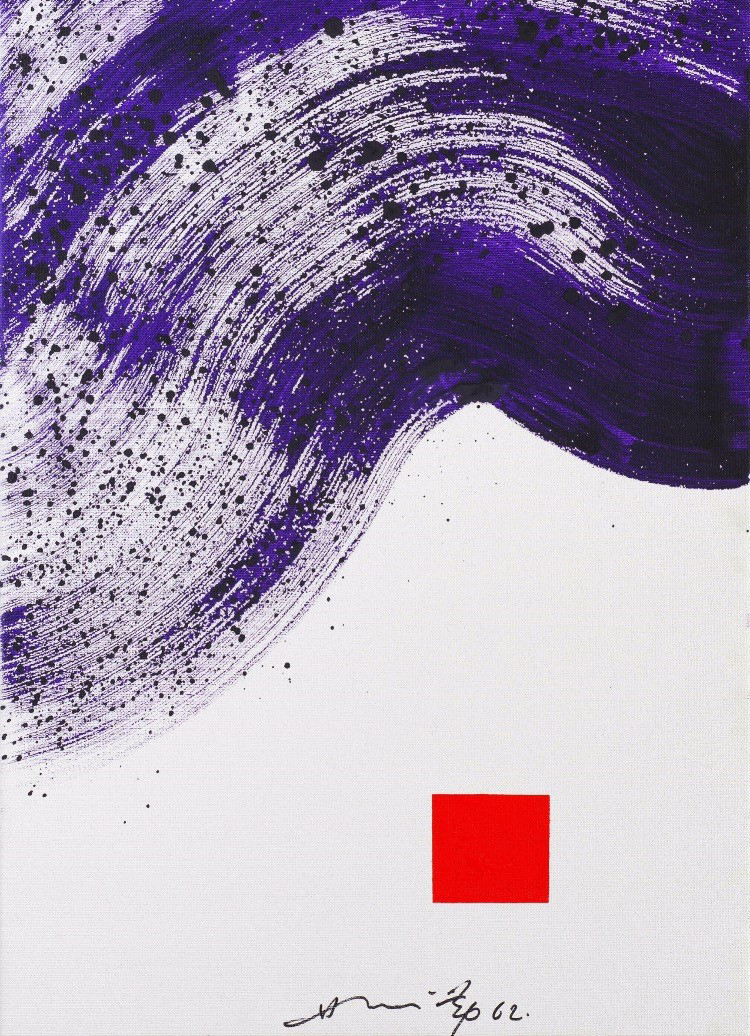

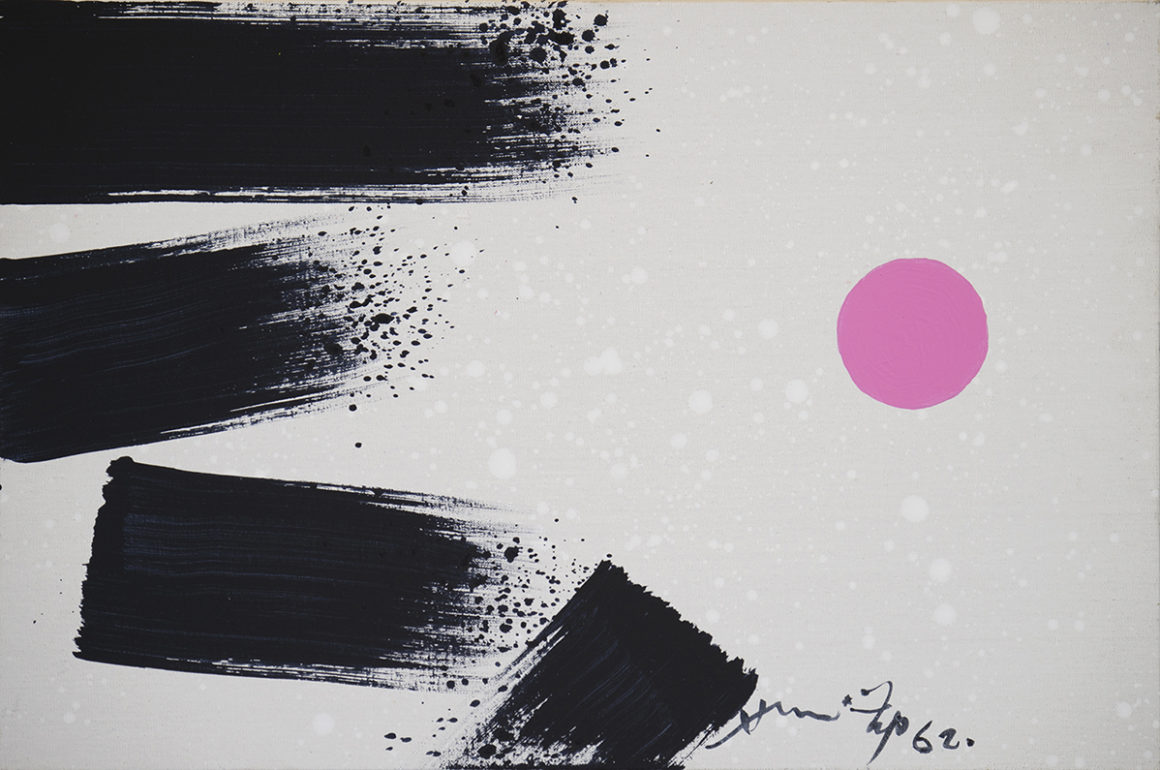

One such artist is Hsiao Chin – a favourite of Hui’s and a master of abstract art in Asia – whose work captures the duality of Taoist philosophy and will be shown in a solo exhibition, PUNTO: Hsiao Chin’s International Art Movement Era at 3812 Gallery next year to coincide with the artist’s 85th birthday. “Hsiao Chin’s work perfectly interprets the ‘Eastern origin in contemporary expression’ principle advocated by Ink Now and 3812 Gallery,” Hui declares. “Though the artist always claims that his work is not Chinese ink, it is obvious to see that Hsiao applies Eastern philosophical thoughts such as Lao Zhuang in Western art.” These influences translate into abstract paintings that merge colourful brush painting with modernist compositions. The show will also include a variety of archival materials that will be shown for the first time outside of Asia.

Read more: Viviane Sassen’s ‘Venus and Mercury’ at Frieze London

And Hui, unsurprisingly, has big plans to take what was once a niche market mainstream. “The objective of having a brand and platform like Ink Now is to materialise the pursuit of art from a cultural perspective to a commercial one,” he enthuses. “Over the last century, particularly in the US and Europe, the shifting influence of culture exported from the East [has transformed] due to political power shifts.” With billions of people now familiar with ink’s cultural language, the discipline is poised to gain widespread popularity.

For Hui, the “Western perspective on Chinese contemporary art was, in a way, too repetitive and rigid while lacking historical and aesthetic context.” Jay Xu, director of the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, agrees that although Chinese inks inspired and continue to inspire Western art, there is still much for us to learn. “Picasso himself once said that had he been born Chinese, he would have been a calligrapher, not a painter, and there was a tablet of Chinese calligraphy on Matisse’s wall. Whether or not Western artists understand the Chinese culture or fully understand the context of ink as a colour and ink as a linear expression, it has inspired many generations of artists both in the East and the West.”

The inaugural Ink Now art expo in Taipei earlier this year

Ink Now is designed to deliver a more nuanced study of the genre by creating a platform for academic discussions, online archives and collectors’ gatherings. Hui’s approach allows an international audience to access material and information in a “globalised community on one’s palm via smartphones,” as well as physically in the gallery spaces and exhibition venues. Ink Now is not merely an art fair; it is “trans-regional and multifaceted”, enabling “international dialogues in various cities”. And, as Hui revealed in our interview, the initiative will be coming to London, perhaps as early as 2020.

Hui knows that the words we use to talk about art are significant, and that the name ‘Ink Now’ underlines the platform’s forward- looking approach to cultural identity. The emerging and established artists promoted by Ink Now create work that is supremely relevant to the issues that preoccupy us in the present. ‘Tech Ink’ is another phrase coined by Hui to refer to our relationship to art in the online age. “Discovering, appreciating, collecting art all happens in the digital realm now. It is a new era; we are particularly fortunate to be part of making new history.”

‘Magical Landscape’, by Wang Jieyin

Liu Kuo-sung is a Chinese artist whose Modernist work is part of this new history. For Kuo-sung, “Ink has always been part of our culture’s DNA,” not just a media but, “really something much deeper. To me, ink is more spiritual.” He believes our era of digital connectivity will help to both influence the market and inspire ink artists. “With the evolution of technology, culture exchange and influence will be easier and faster. During my early career, information [was] scarce and I needed to either borrow a catalogue from a public source or physically go to a museum or gallery to see artworks. Today, you get so much information without needing to leave your house.”

Read more: Spanish artist Secundino Hernández on flesh & creative chaos

Museum director Jay Xu thinks the medium could even challenge the lens through which we view art history. “From the Renaissance, the scope and definition of art has been evolving, and though art has been regarded [in relation to] a Western canon, what ink could possibly do is to rethink the canon of art in general. It is a much more diverse world that we live in now. The global phenomenon must include artistic expressions of all cultures and regions, in which each have their own definition of what art is.”

The art form finds perhaps its most modern expression when machines are involved in its creation. “Digital art is definitely a trend, especially in the Western market,” Hui points out, citing Victor Wong’s artificial intelligence ink paintings, a collaboration between the artist and his AI assistant, Gemini. The robot that Wong programmed has created a fascinating, meticulous body of shuimo ink work, heading into uncharted artistic territory and prompting a wider discussion on AI artworks and the definition of art.

The relationship between traditional and contemporary inks is one duality that is explored in the art form; the tension between Western and Eastern influences is another. Jay Xu cites artist Xu Bing and his ability to “create scripts writing English alphabets in Chinese calligraphic strokes – an iconic mode of expression that is part of the ongoing evolution of calligraphy.” The museum’s 2012 exhibition, Out of Character: Decoding Chinese Calligraphy, featured works from the Jerry Yang collection, including animated calligraphy by Bing and “juxtaposing Western abstract expressionism with ink art to form a dialogue”.

Here: ‘L’inizio del Dao-2’ (1962); above: ‘L’Origine del Chi-3’ (1962), both by Hsiao Chin

As both a gallery owner and a collector, what does Hui think about mixing business with pleasure? “The inevitable marriage of art and investment is an agreeable phenomenon; however, the danger of treating art solely as an investment means to neglect its artistic value while focusing on the price. Art should always be about value, not the market price.” Value should be established first, and the market should follow. “As an art consultant, I take great precaution in investing in art. It is crucial to know the difference between cultural assets and financial products. The art market is much more complex, with different factors and less regulations and compliances than the financial sector.”

There is no doubt that the ink art market is growing: “The regional market in China itself is an important index on the one hand, but on the other, acceptance and exposure in locations such as London provide outlooks for the market trends.” As a gallery owner, Hui has a track record of successfully bringing works by celebrated regional artists onto a more international stage, and platforms like Ink Now often mark the beginning of a surge in the market; the growth of the contemporary African art scene in London and New York followed a similar trajectory. Ink Now’s strategy is to focus on ink art, “not just as a category, but rather as a set of mutual cultural linguistics that bridge various cultures and markets together.”

Read more: Louis Roederer’s CEO Frédéric Rouzaud on art and hospitality

Calvin Hui and Ink Now’s mission has artist Liu Kuo-sung’s backing: “As an artist, we need to understand our mission in life is not only to create good art, but also to leave a mark or make a contribution to our culture and civilisation. Ink art has evolved so much in the past 50 years. Today, young ink artists are creating some amazing new forms of ink art, and I have also seen some great ink art works from Western artists as well.”

On the business of collecting, Hui is equally passionate: “Mankind is drawn to collect, it is in our nature. Owning art is owning experience, emotion, and a piece of the past, it should have a story of its own, to have an interaction with the collector. It is a highly individual and subjective act. One should always collect what one loves. Buying art should not always be about investment. It is about the purest form of passion. I only buy what speaks to me, something I can engage on a deeper level.”

And what was the first piece of art that Calvin Hui collected? A lithograph by Joan Miró, an artist who was fascinated by Eastern culture and who incorporated calligraphy and ink art into his oeuvre. In other words, the artwork that Hui first chose was not only a testament to his impeccable taste, but a glimpse into his future.

Find out more: ink-now.com/en

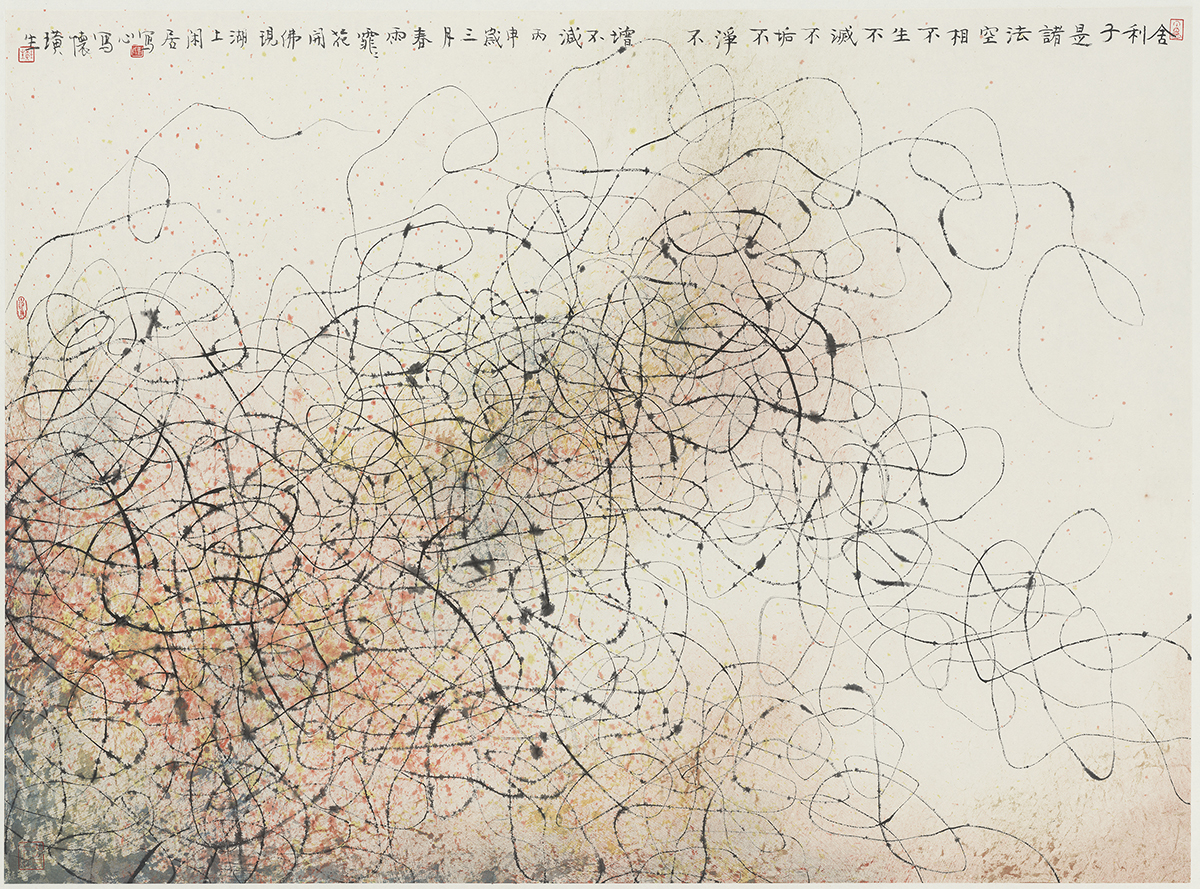

‘Moving Vision: Neither Dying or Being’, by Wang Huangsheng.

Calvin Hui’s six artists to know

Wang Jieyin

From the start of his career, Shanghai-based Wang Jieyin has been inspired by the cave paintings in Dunhuang. His contemporary take on ancient Chinese art results in artwork with a muted palette, a focus on natural shapes and romantic, abstracted depictions of landscapes.

Chloe Ho

Chloe Ho’s ink art references both her American and Hong Kong background with unexpected elements such as coffee and acrylic paint. Her exhibition, Unconfined Illumination, runs at 3812 Gallery in London until 15 November.

‘Volcano;, by Chloe Ho

Wang Huangsheng

Living and working in Beijing, Wang Huangsheng is a curator and professor whose minimalist contemporary ink drawings convey a range of moods, suggest landscapes and allude to calligraphy.

Victor Wong

Victor Wong’s debut in TECH-iNK is a breakthrough in combining technology with art, calling into question our definition of art and culture, while creating highly detailed, original ink depictions of surfaces, such as the moon.

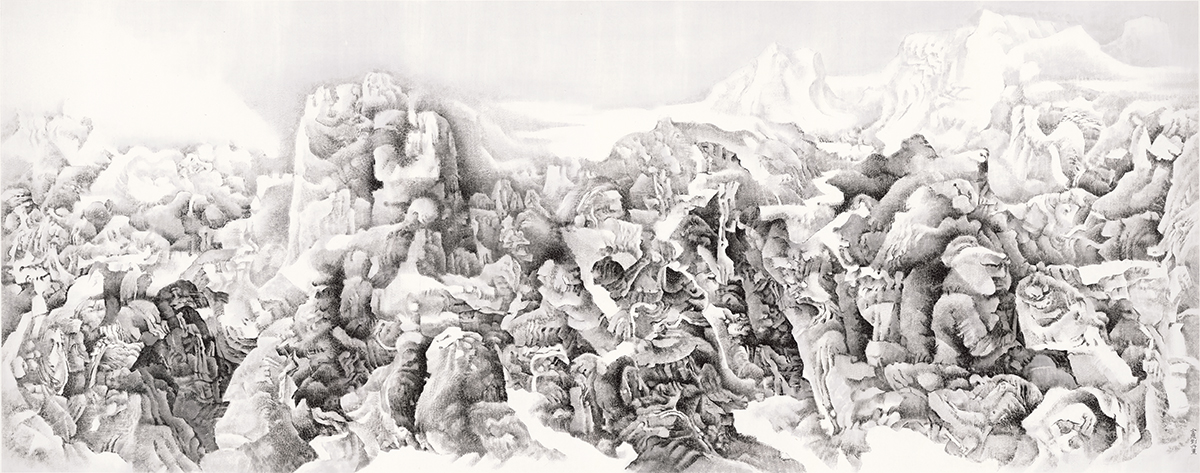

‘Contraction and Extension of the Twilight’, by Liu Dan

Liu Dan

Liu Dan is known for the contemporary twist he applies to his organic, shaded landscapes, devoting himself to detailed studies of flowers and rocks using Chinese ink and brush techniques.

Hsu Yung Chin

Hsu Yung Chin’s practice incorporates both writing and painting, merging boundaries between the two forms of expression, and breaking all the traditions of calligraphy in order to create works that feel relevant to contemporary Chinese society.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 19 Issue.

Recent Comments