Wes Anderson and Juman Malouf at Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien. Photo: Christian Mendez

Following the exhibition’s first home at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna earlier this year, Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures has moved to Fondazione Prada’s gallery space in Milan with larger displays and more exhibits than its original incarnation.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxresponsibleluxury

Curated by Wes Anderson and Juman Malouf, the exhibition explores the history of collecting in museums, stripping the barriers of traditional gallery shows and embracing the concept of the kunstkammer (cabinet of curiosities).

Installation view of ‘Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures’ at Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, showing the Coffin of a Spitzmaus (Shrew), c. 4th century BC. Photo: Jeremais Morandell. Courtesy KHM-Museumsverband

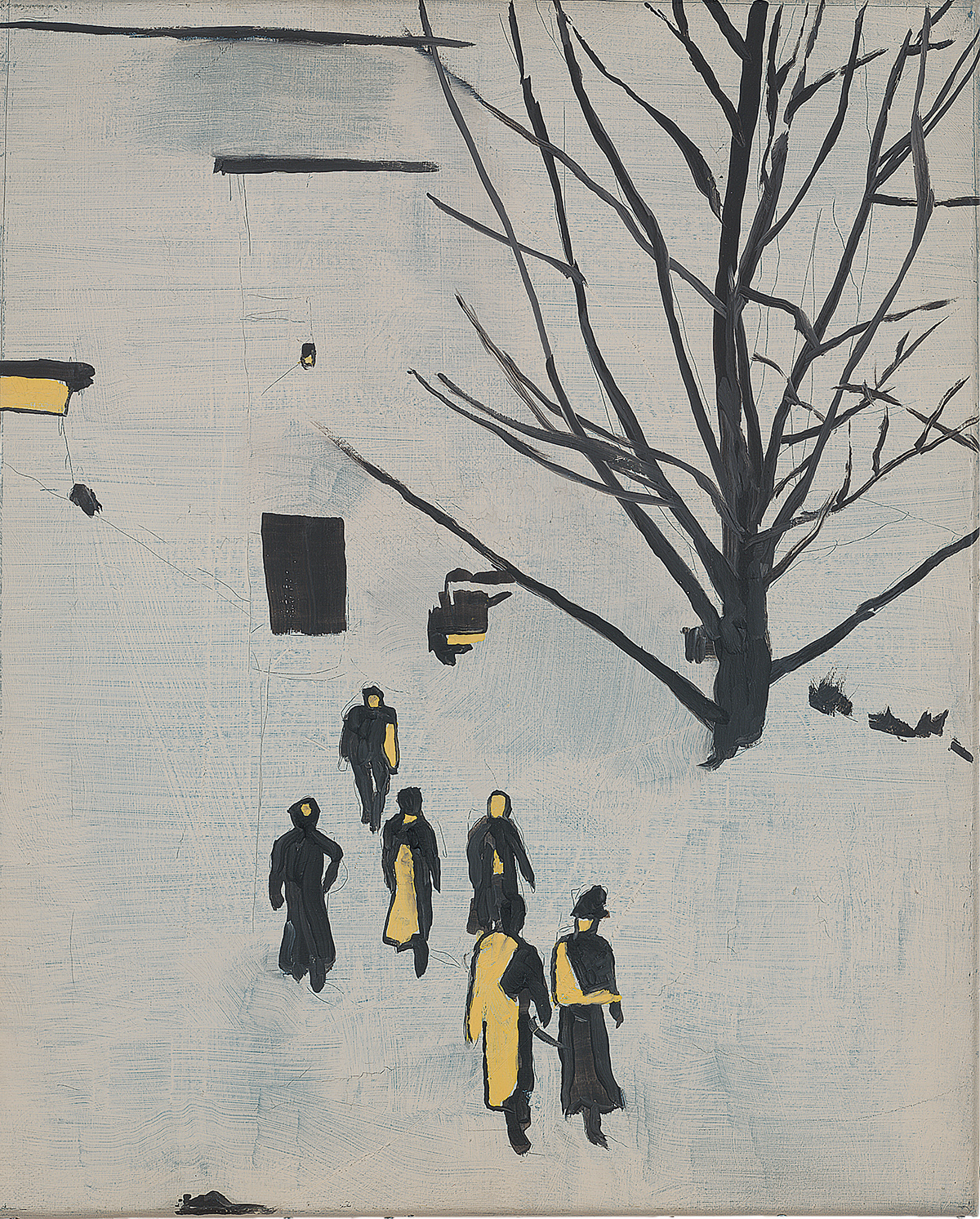

‘A Philosopher of Antiquity’, Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo, c. 1520/30. Photo: Jeremias Morandell. Courtesy: KHM-Museumsverband

The show’s eclectic display focuses around an unusual star object: the sarcophagus of a shrew. The Spitzmaus coffin (its name comes from the German word for shrew) is a small vessel, gilded and painted with the silhouette of a mouse. Dating from the 4th century BC, it was designed to hold the Egyptian mummified remains of a sacred shrew. The coffin – along with all of the other pieces on display – was selected by Anderson and Malouf from the vast archives of Kunsthistorisches Museum and the Naturhistorisches Museum in Vienna, and perfectly encapsulates the quirky aesthetic of the exhibition as a whole.

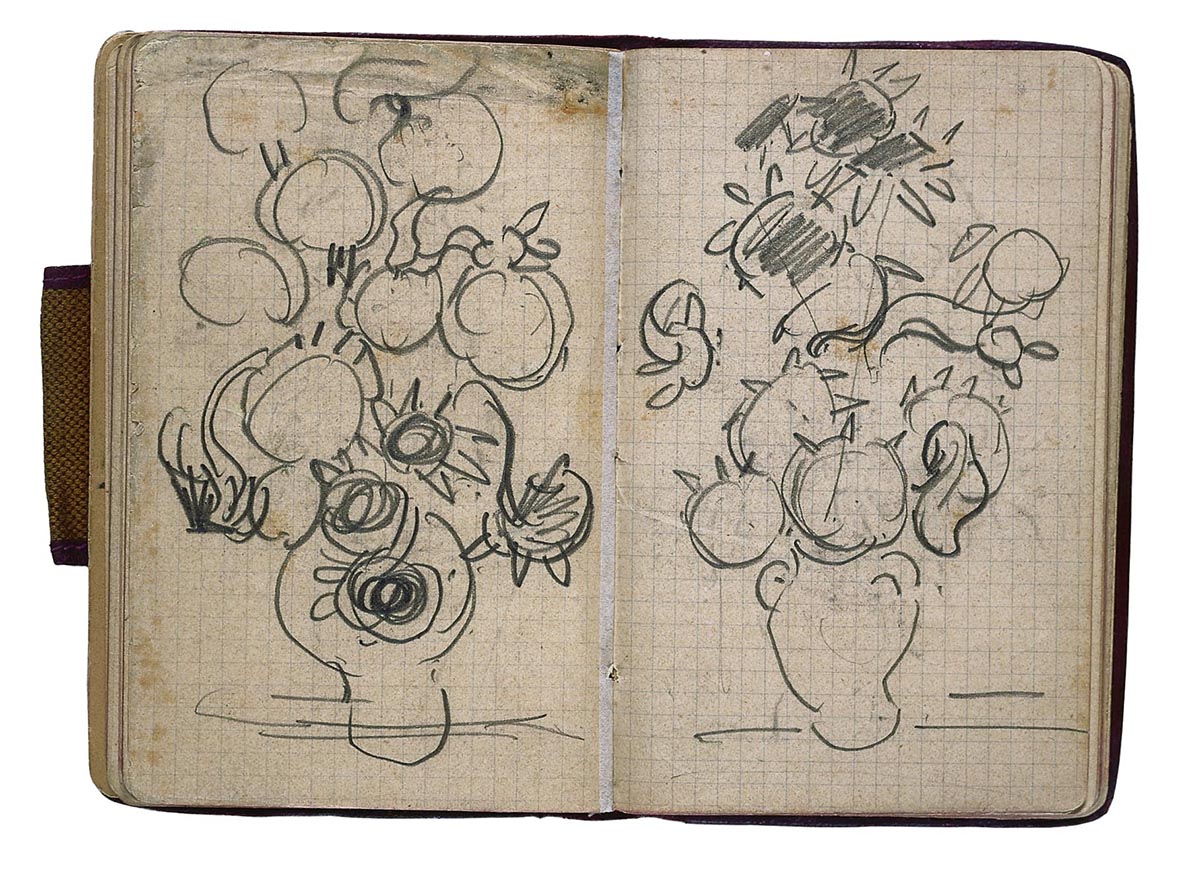

Unknown, XVIII Sec. Photo by Jeremias Morandell. Courtesy KHM-Museumsverband

This is the Kunsthistorisches’ third exhibition in seven years to welcome creative individuals as curators. Following curations by Ed Ruscha and Edmund de Waal, Anderson and Malouf were selected for their clear artistic vision, unique style and attention to detail. We can see this in many of the pieces they’ve chosen: often small and ornate with a focus on unusual materials, their displays bring together a selection of natural and man-made objects and artworks, presented in separate cases or in clusters.

Read more: Mustafah Abdulaziz wins 2019 LOBA photography award

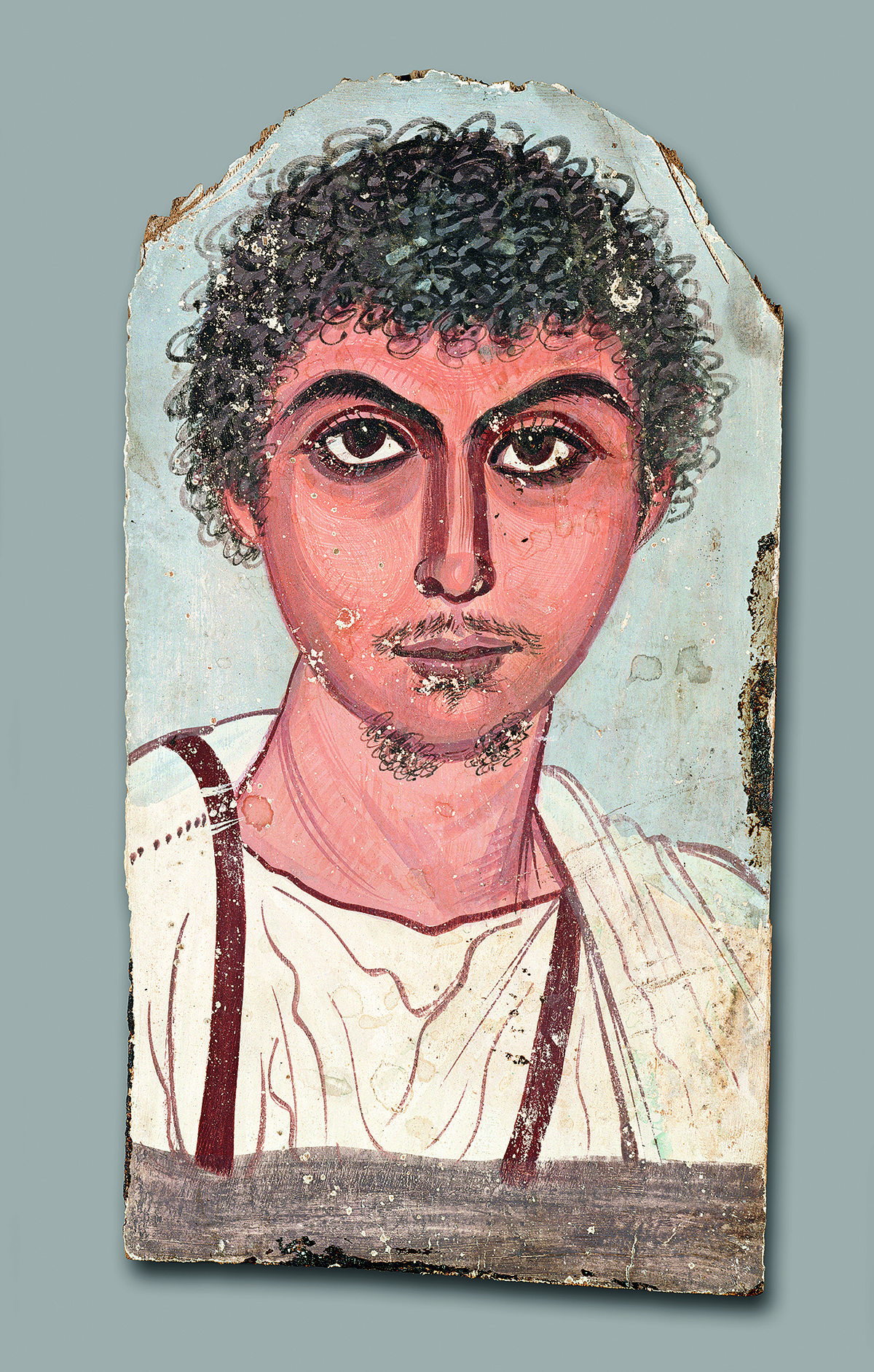

‘Mummy Portrait: Young man with fuzz’, Roman, Early Antoine, 2nd quarter 2nd cent. AD. Courtesy: KHM-Museumsverband

Each room shares a distinct quality, that seems to resonate with both Anderson’s and Malouf’s creative universe. In fact, the whole exhibit appears much like the perfectly staged Kunst Museum that Jeff Goldblum is chased through in The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Rosie Ellison-Balaam

‘Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures’ runs until 13 January 2020 at the Fondazione Prada in Milan. For more information visit: fondazioneprada.org

Recent Comments