The health of the world’s oceans is under threat. But the seas can be part of a visionary plan to address climate change and create a more sustainable economy. Andrew Saunders reports on the new science around ocean carbon capture

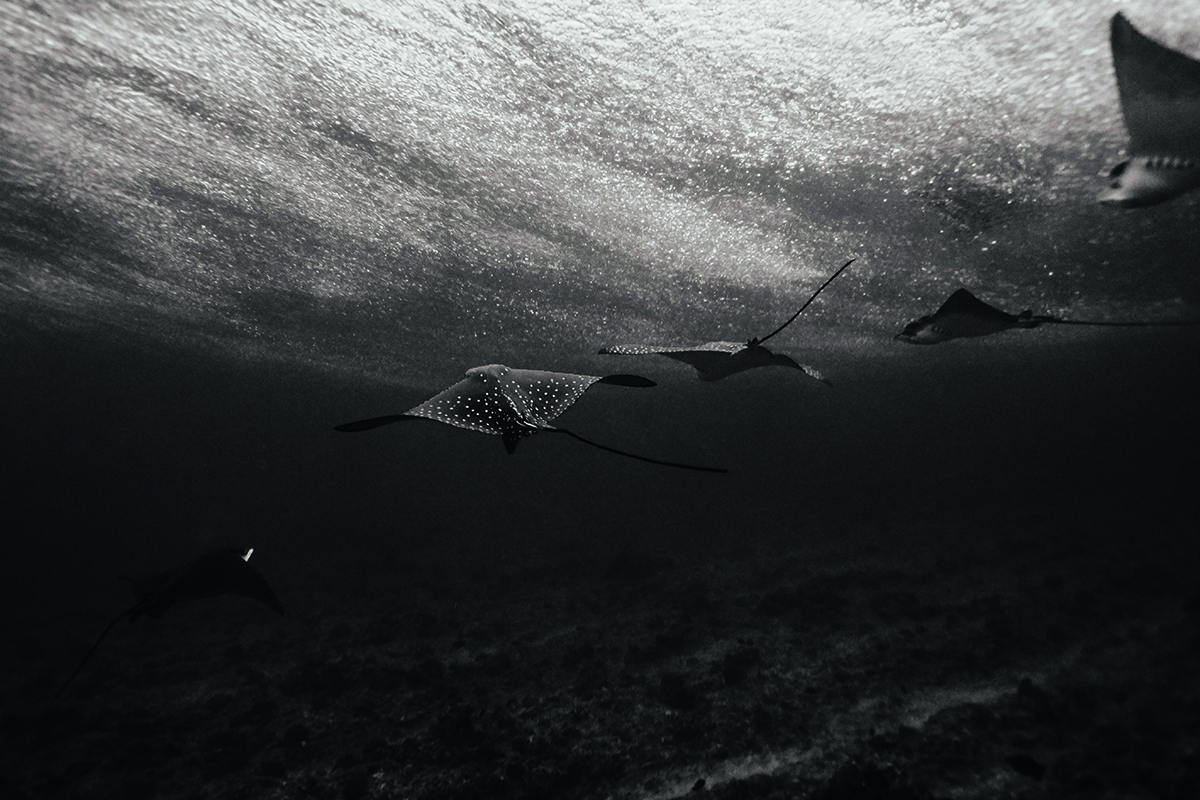

Photography by Matt Sharp

The power of plants to absorb excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as they grow is well understood as a vital tool in the global battle against climate change. But which of the planet’s myriad natural environments does it best? Tropical rainforest? African Savannah? Scottish peat bogs? None of the above – in fact the most carbon-rich ecosystem in the world is not to be found on land at all but in the ocean. Mangrove swamps, such as those found dotted around the coastlines of Indonesia, Brazil and Nigeria for example, are the unsung heroes of carbon storage, locking up no less than ten times as much carbon per kilometre square in their branches, roots and soils than even the densest forest.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Together with other coastal ecosystems, including sea-grass meadows, tidal marshlands and coral reefs, these so-called ‘blue carbon’ resources highlight that the oceans play a much more prominent role in limiting global warming than has been generally recognised.

“Building the ocean’s resilience to change and helping to rebuild marine-species abundance and diversity are not as fully appreciated as they should be as crucial tools in combating climate change, but there is more and more evidence that blue carbon plays a critical role in maintaining the health of our biosphere,” says Karen Sack, chief executive of Ocean Unite, an international network of experts in the science and ecology of the oceans.

Covering some 70 per cent of the planet’s surface, the oceans are effectively a huge carbon sink which has already absorbed around a third of the excess carbon that has been put into the atmosphere since the dawn of the industrial era. And more than 50 per cent of the carbon in the ocean is blue carbon, despite the fact that such environments account for only two per cent of the total ocean area. Protecting and enhancing them is at least as important as preserving forests, planting trees and rewilding on land, says Sack. “Mangroves, sea-grass beds, fish and marine mammals play a huge role in sequestering and storing carbon. By protecting and restoring these crucial habitats and species, more carbon will be sequestered and stored, resulting in a healthier planet, which is better for us all.”

Rock pools in Jersey

The carbon capture and storage potential of healthy oceans is not limited to coastal blue carbon zones alone, however. Other proposals for boosting the potential carbon sequestering of the world’s seas include encouraging kelp forests – essentially huge seaweed farms – and even microscopic algae called phytoplankton to extract carbon from the atmosphere as they grow.

Such initiatives could not only help climate change but also present new and potentially lucrative opportunities for business and investors, says Professor Ove Hoegh-Guldberg of the University of Queensland and a member of the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy. The panel’s landmark 2020 report, Ocean Solutions That Benefit People, Nature and the Economy, found that a truly sustainable ocean economy could contribute around a fifth of the total carbon reduction required to meet the 2015 Paris Agreement target of a maximum two degrees of climate warming.

Read more: LUX Editor-in-Chief Darius Sanai on Effective Climate Action

For example, some phytoplankton species can be a source of valuable low or even zero-carbon biofuels and other industrial products. “Some of my colleagues here in Queensland are working on this. Phytoplankton grow very quickly and they can be processed to produce biofuels and high-value boutique chemicals. It’s potentially very interesting but it still has to be proved at an industrial scale.”

The ocean economy could also help feed the world more sustainably – a study by the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies found that each kilo of fish landed in the US requires the emission of just 1.6kg of carbon dioxide, compared with between 50kg and 750kg for a kilo of beef produced on land. And if it can be done sustainably, large-scale ocean aquaculture has the potential added benefit of helping to protect and restore many wild-fish stocks threatened by over-fishing. “Well over half the world’s fisheries are in trouble,” says Hoegh-Guldberg, “because they have been fished down to well below sustainable levels.”

Rethinking the way we catch fish, so that sustainable aquaculture in the oceans becomes more equivalent to sustainable agriculture on land, could help stressed wild fisheries recover, he adds. “We are sophisticated farmers on land but we still have a basically Neolithic culture when it comes to fisheries.”

Creating such a climate-positive ocean economy will require a shift in the mindset of business in general and finance in particular to the point where the environmental impact of commercial activity is given equal weight to considerations of profit and loss, says Ocean Unite’s Sack. “Instead of viewing nature as an unaccounted externality that is not valued, the finance and business community more broadly needs to recognise its value, including the intrinsic value of biodiversity, and account for it. It can then take tried and tested financial products and put them to work with nature to build resilience and deliver bankable returns.”

Matt Sharp visited the Maldives in 2019 (above) where he recorded the extent of the pollution on the beaches

Stressing the urgency, she continues, “We’re at an ‘all hands on deck’ moment. By bringing together our collective knowledge and strengths, we can tackle hazards and vulnerabilities, build resilience and adapt to change at speed and at scale. But we have to have public and private sector financing to do that and partner across sectors to spur the type of innovative marketplace that is needed.”

So, nature and profit can co-exist in a sustainable and carbon-sequestering ocean economy. But what about technological solutions? As far back as the 1970s, Italian physicist Cesare Marchetti was the first to suggest injecting CO₂ directly into the Mediterranean to ameliorate global warming, and since then the oceans have been seen as part of a more tech-led – and more controversial – approach. Subsequent refinements of Marchetti’s original idea include pumping CO₂ captured from industrial plants into the sediment layer on the deep ocean floor. The pressure at such depth would liquefy the carbon dioxide, helping – in theory anyway – to keep it safely locked up, miles down in the mud.

Read more: Markus Müller on the Importance of Global Sustainability Standards

Even set against the current scale of the climate crisis, this looks like last-ditch stuff, says Professor Stuart Haszeldine of the School of GeoSciences at Edinburgh University. “I would much prefer that we didn’t have to: it would be a last-resort type of measure, if we haven’t managed to re-capture our emissions in any other way.”

But all the same, less risky technological solutions may well have a place – and the ocean can be part of that, too. Haszeldine and his colleagues at Edinburgh have come up with an alternative plan that could see the ocean surface turned into a kind of giant mirror to reduce the heating effect of the sun. Autonomous, computer-controlled ships would suck up sea water and spray it into the air as fine droplets, forming a layer of mist to reflect sunlight and cool the waters beneath. “We should have started reducing our carbon dioxide emissions 30 years ago,” he says. “This would be a way of cooling the ocean quickly, to reduce the effects of hurricanes [also caused by rising sea temperatures] and of helping to refreeze the melting arctic ice.” The group is currently looking for funding for a trial project to turn its innovative idea into reality. “We could build a pilot boat for a few million, and if it works then building 300 of those to delay the climate problem is well within the capacity of the global shipbuilding industry.”

Spotted eagle rays in the seas around the islands in the Maldives

The ocean surface could also be a platform for renewable power generation, thanks to the developing technology of floating wind and solar farms, says Hoegh-Guldberg. “Our report concludes that there is enormous potential there, and it is both technologically feasible and acceptable to the public.”

So while the climate clock is ticking ever more loudly, there are grounds to be cautiously optimistic that an alliance between science, government and business will yet provide the framework, the finance and the innovative ideas required to keep global warming within just about tolerable limits, and that oceanic carbon capture and storage will play its full part in the process. In Hoegh-Guldberg’s view, “Government needs to set the rules to encourage science to define the problems and the solutions, but then it should be sitting back as business gets involved.”

Hoegh-Guldberg also warns that if we continue as we are, we will end up with a world that is three to four degrees warmer than the pre-industrial era. “So, it doesn’t look too good as it stands now. But humans are very resourceful and there are lots of opportunities. I think we will keep to under two degrees, though not by a lot. Transitions tend to happen very slowly at first; you have to push and push until you get to the inflection point. Then suddenly you’re rolling downhill on the other side.”

Matt Sharp was awarded the Ocean Conservation Photographer of the Year in 2020. He studied marine biology and has travelled and worked around the world, documenting marine life.

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2021 issue.

Recent Comments