Lindblad Expeditions travellers explore Booth Island, Antarctica

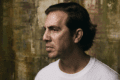

Sven-Olof Lindblad is an influential Ocean Elder whose work combines marine conservation, education and eco-tourism. He speaks to Sophie Marie Atkinson

In late January 1966, 57 travellers arrived at Smith and Melchior Islands on the Antarctic Peninsula aboard a chartered Argentine navy ship. Pioneer Lars-Eric Lindblad was the man behind this voyage, one which had previously only ever been undertaken by professional explorers and scientists. This event marked the beginning of commercial travel to parts of the world that, until then, most could have only dreamt of visiting, as well as the birth of a whole new industry.

Exploration, discovery and an innate desire to immerse oneself in nature clearly run in the Lindblad blood. Lars-Eric’s son, Sven-Olof, spent part of his life in east Africa, where he photographed elephants and wildlife and assisted filmmakers on a documentary about the destruction of rainforests. This experience, coupled with the many trips he joined his father on, ignited a passion that lives with him today.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

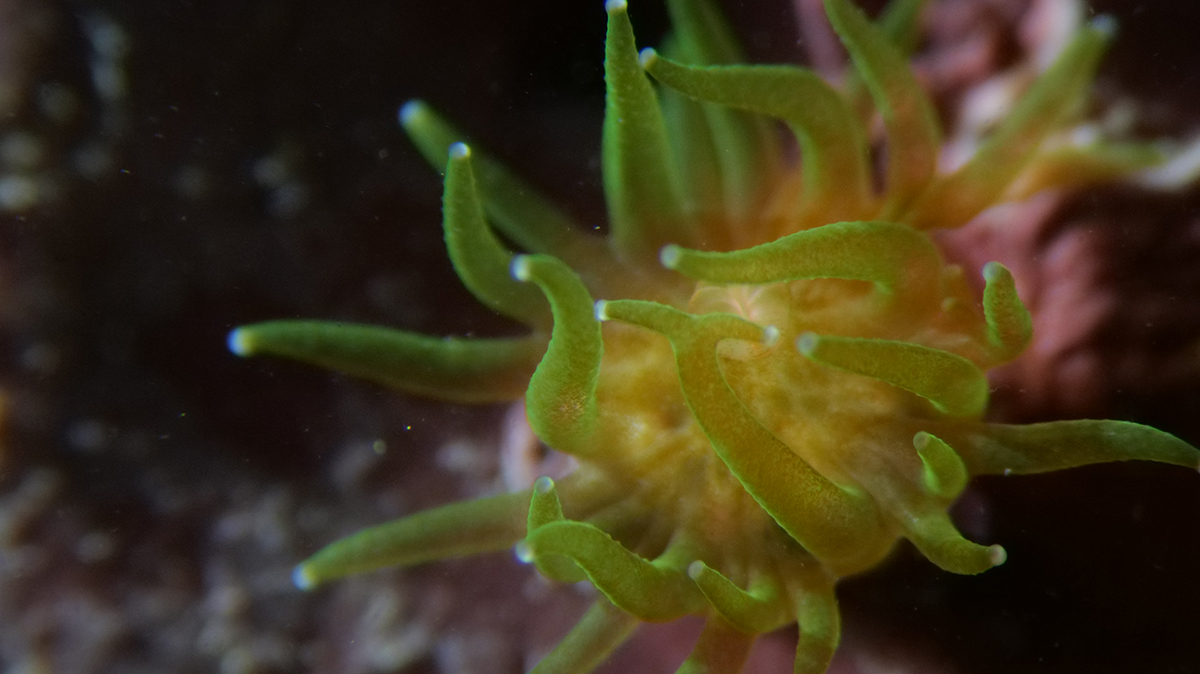

By 1979, Sven-Olof had founded Special Expeditions (now Lindblad Expeditions), an innovative travel company that today offers oceanic expeditions aboard small ships. Like his late father (who died in 1994), Sven-Olof’s mission is to enable people to explore hidden corners of the world. Destinations include the coast of Alaska, Baja California, Patagonia, Russia, and even the islands around Scotland. But visiting these regions is only a fraction of the company’s story.

Lindblad Expeditions seeks to take what we currently call ‘sustainable travel’ a step further. “Sustainable travel basically means that you can just continue what you’re doing without causing a negative impact, so essentially ‘do no harm’,” Sven-Olof explains. “I think what we need to do is figure out how to use our energy and our imagination to think more in restorative rather than just sustainable terms. We’ve done so much damage to our environment that we need to shift gears fast.”

Sven-Olof Lindblad on Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic, 2014

This is why planetary stewardship and meaningful change are at the heart of the Lindblad Expeditions offerings. They are facilitated in a number of ways. Firstly, the company is carbon-neutral, offsetting all its operations and making it easy for travellers to do the same with their flights. The ships are entirely free of single-use plastic, and all food provided on board is responsibly sourced.

The company has formed a partnership establishing the Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic Fund, with donations often coming from inspired passengers, with each of the 15 ships raising finance for different programmes. “We have a hugely successful project called Pristine Seas,” explains Sven-Olof, “the objective of which is to create large marine protected areas. We raise a minimum of $500,000 a year for that programme, often up to $800,000.

Read more: How Science is Harnessing the Power of the Sea

“In the Galápagos, we put hundreds of thousands of dollars into a local school that we believe will educate the future leaders of the islands.” They also help local fisheries implement better technology for their work.

Motivating people to care is another piece of the Lindblad puzzle. “One of the things I love about having this fund is its action, which we often see in the most surprising ways,” he says. “One individual had travelled with us at first to Alaska then to Baja California and then to the Galápagos. He called me one day and said, ‘I’m a trustee of The Helmsley Trust and I’m fascinated with what you do.’ Over a number of years, he became the trust’s most significant conservation investor. He was pumping $9 million a year into the Galápagos and about $6 million into Baja. He had never thought about this field before and these trips just opened his eyes.”

Sven-Olof doesn’t see any of his efforts as philanthropic. “I’ve made a point, in relation to our industry, never to use the word ‘philanthropy’,” he says. “If we gave $100,000 to the children’s hospital in New York, I would view that as philanthropy, but when it comes to anything related to travel, I view it as investment. At the end of the day, natural resources, cultural resources, historic resources – these are what the travel industry depends upon. So why wouldn’t we naturally want to invest in the maintenance of these, our core assets?”

On top of these myriad achievements and endeavours, Sven-Olof is one of 23 global leaders – including Jean-Michel Cousteau (son of Jacques) and James Cameron – who use their power and influence to protect our marine worlds. These are Ocean Elders. Sven-Olof explains that their primary purpose is to try to sway political decisions, or lobby governments or certain businesses. “There are a lot of scientific resources behind Ocean Elders owing to the fact that members include the likes of Richard Branson, which means we can produce weapons that we can put on desks of prime ministers, weapons signed by all of these people.”

It would appear that Sven-Olof Lindblad, with a fleet of 15 ships and the backing of some heavyweight peers, is more than armed and ready for the war against the destruction of our precious oceans. His role at the helm of eco-travel looks set to continue.

Find out more: world.expeditions.com

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter Issue.

Recent Comments