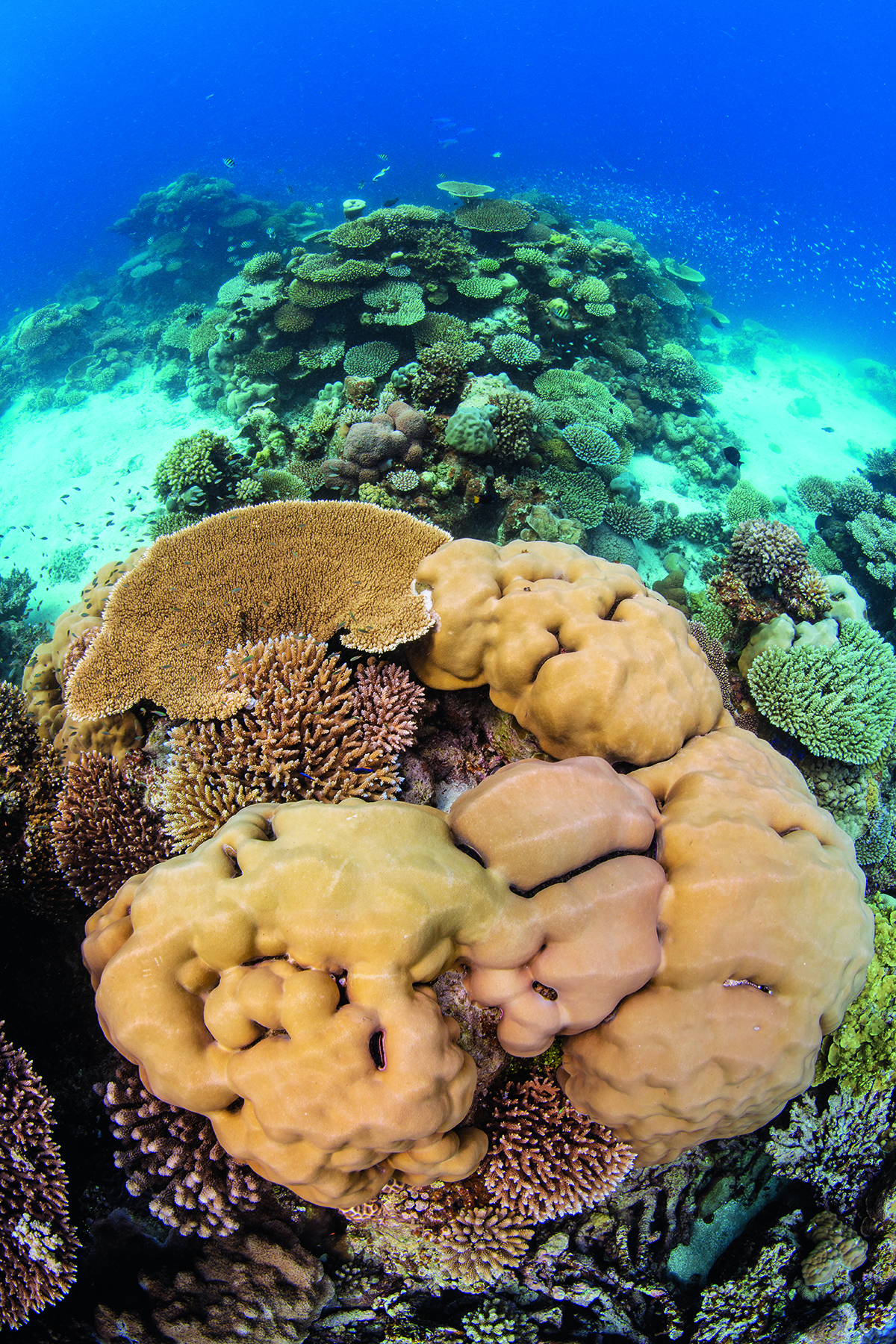

Alex Mustard photographed healthy reefs in the Maldives

As our oceans warm up, the spectacular coral reefs of the Maldives archipelago are dying. Michael Marshall reports on the new philanthropic project aiming to make them more resilient to climate change

Beneath the glittering cerulean waters of the Maldives archipelago, trouble is brewing. The extraordinary coral reefs that encircle these islands are being damaged by climate change, threatening the country’s very survival.

Fortunately, help is at hand. A local research and conservation institute has bold plans to strengthen the reefs by breeding the most resilient corals and seeding them in the waters of the Maldives. With the help of a new philanthropic initiative, led by Deutsche Bank, the project is ready to set sail.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

The Maldives is one of the countries most affected by climate change. “You couldn’t find a place more in the front lines,” says Callum Roberts, Professor of Marine Conservation at the University of Exeter.

As the Earth’s temperature warms, driven by greenhouse gas emissions, the oceans are being reshaped. Most obviously, sea levels are rising – and for low-lying islands like the Maldives that is an existential threat. But there’s more: seas are warming, the water is becoming more acidic and low-oxygen zones are spreading. These changes threaten all marine life.

Climate change poses a particular threat to corals. These tiny animals live in huge colonies underwater, and over thousands of years the skeletons of dead corals build up to make vast structures called reefs. The Maldives themselves are coral reefs that grew until they reached the surface, and the country’s islands are ringed by underwater reefs. These are home to an extraordinary range of animals, from sharks to starfish.

More photography by Alex Mustard of healthy reefs in the Maldives

“Your first experience of a coral reef is completely unforgettable,” says Roberts. “You dive over the reef crest and into that area where it’s just a huge blaze of fish of all varieties and colours.” It’s utterly immersive, he adds; you can “feel yourself being completely consumed by an ecosystem”.

Corals are particularly vulnerable to warming. “It doesn’t take more than a rise of about 1°C above their normal thermal maximum for corals to get into deep trouble,” says Roberts. “That’s what’s been happening.”

Callum Roberts

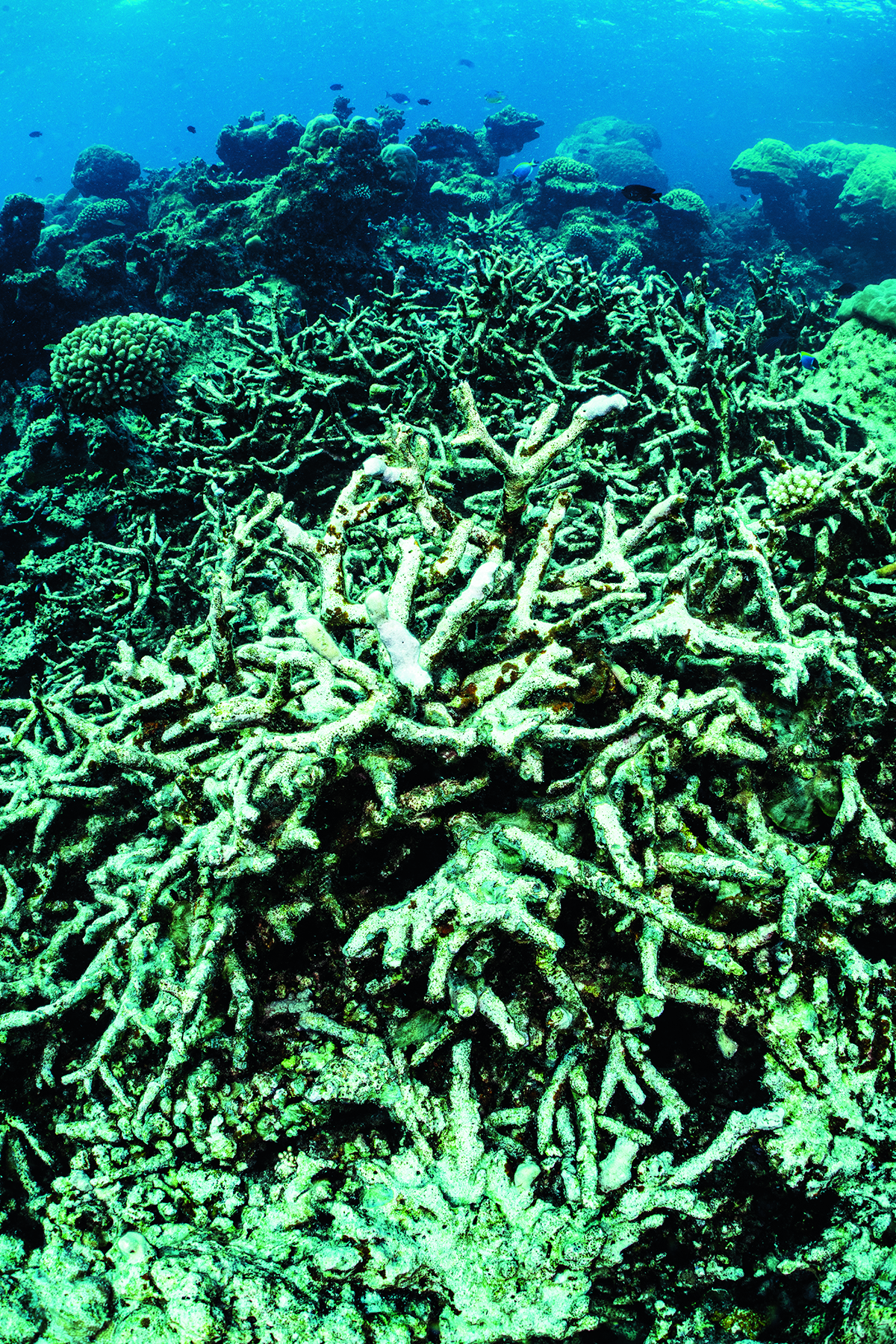

In 1997-98 and 2015-16, spikes in ocean temperature caused mass coral bleaching events. The corals expelled the algae that live inside them and that they depend upon for nutrients. As a result, the corals turned ghostly white. The first bleaching event killed an estimated 95 per cent of shallow corals. They then underwent a partial recovery, before the second mass bleaching event caused about 65 per cent mortality. “That level of coral death is extremely worrying,” says Roberts.

In a 2018 report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated that “coral reefs would decline by 70-90 per cent with global warming of 1.5°C, whereas virtually all would be lost with 2°C.” So far, the Earth has warmed by an estimated 1.1°C.

To save the corals, and by extension the Maldives, the country’s former president Mohamed Nasheed founded the Maldives Coral Institute (MCI). The MCI aims “to help coral reefs to survive and adapt to the changing climate”. Roberts is one of its scientific advisers.

Alex Mustard also photographed bleached, dead corals highlighting the abundance of sea life at risk if corals are left to decline

The MCI is now being financially supported by Deutsche Bank. In November 2021, the bank launched its Ocean Resilience Philanthropy Fund, which is intended to support nature-based solutions to marine conservation problems. Deutsche Bank committed an initial $300,000 and hopes to raise $5 million over the next five years. The MCI was brought to the bank’s attention by Karen Sack, Executive Director and Co-Chair of the Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance.

Jacqueline Valouch

“The lack of funding is one of the big recognised barriers to nature-based solutions,” says Jacqueline Valouch, Head of Philanthropy at Deutsche Bank Wealth Management in New York, who was involved in setting up the fund.

“We’ve got this massive problem, the Maldives Coral Institute has a mission, and Deutsche Bank is funding a really important piece of work to begin with,” adds Roberts.

The funding will enable the MCI to launch a project called the Future Climate Coral Bank (FCCB). The idea is to find corals that have proven resistant to climate change and breed them in a controlled environment, creating more resilient strains. “We’re going to have a living propagated coral farm underwater in which the idea is to explore and test ways of assisting evolution,” says Roberts. These resilient corals can then be reintroduced to the ocean, particularly to reefs with a poor supply of coral larvae. In the long run, this will hopefully mean the Maldivian corals become more resilient.

The MCI works on conservation projects including this one at Fulhadhoo, where divers installed a silt screen to prevent sediment from nearby construction from damaging the corals

“The magnitude of that impact to us was unmatched in many ways,” says Valouch. She says the FCCB “could last for many generations,” which is crucial, because her philanthropic clients want “to make an impact on the causes they care about”. “They’re multigenerational families coming from many different regions of the world and they have their family members living in different parts of the globe.”

Valouch and her colleagues plan to spend much of 2022 talking to donors. “We are looking to kick all that off now,” she says. A key element will be introducing prospective donors to the project team, so they can appreciate the talent and passion of all involved. Deutsche Bank is also recruiting a panel of experts who will advise on which projects to fund. “To be able to have that kind of innovation and creativity sit at the table with us is just extraordinary,” Valouch says.

For her, philanthropy can provide the seed funding for ambitious projects such as the FCCB. “It allows other donors to come in,” she says, and enables organisations like the MCI to recruit enough staff to become sustainable.

“I think the private sector has a greater appetite for risk,” says Roberts. That’s especially true for projects such as the FCCB. “This is not research that ends when you publish a study. This is something that has to make a difference on the ground and in the water.”

The hope is that, with the right investment, the corals of the Maldives will thrive for decades to come.

Five approaches to regenerating the world’s coral reefs

- Reducing agricultural runoff into the sea improves water quality and coral health.

- Coral IVF grows baby corals in the lab and seeds them on damaged reefs.

- Artificial reefs can be sunk in oceans to provide homes for corals and other sea life.

- Corals can even be given ‘probiotics’ to help boost their health.

- Most importantly of all, limiting climate warming to a maximum of 1.5°C and lowering global greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero will minimise the threat to the world’s coral reefs.

— Michael Marshall

Former President of the Maldives and environmental activist Mohamed Nasheed discusses climate change with children at the Maldives Coral Institute’s Coral Festival in 2020

A partnership of positive steps

The Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance (ORRAA) is helping to drive a global response to ocean-derived risks. Backed by organisations ranging from the World Wildlife Fund to Deutsche Bank as global lead banking partner, it wants to save the oceans by deploying the power of the financial world.

Read More: Jean-Michel Cousteau: Choose Life

Its mission is “to pioneer new and innovative financial products” that will tackle climate change, protect ocean biodiversity and help coastal communities become resilient, says Karen Sack, Executive Director and Co-Chair of ORRAA.

Karen Sack

“We aim to drive at least $500 million of investment into coastal and marine natural capital, or ‘blue nature’,” says Sack. She argues that this is in everyone’s interest. The global ocean economy has a total asset value estimated at $24 trillion, but in the past decade only $13 billion has been invested in sustainable marine projects. “We need to change that,” says Sack. “And we need to act quickly.”

Hence the Maldives project. Deutsche Bank were looking for ways to have a positive impact quickly, as well as over the long term, and Sack suggested supporting the MCI. “Lessons learned in the Maldives will help heal and strengthen coral reefs around the world.”

Michael Marshall is a renowned science journalist specialising in the environment and life sciences

Find out more: deutschewealth.com/oceanfund

This article appears in the Deutsche Bank Supplement of the Summer 2022 issue of LUX

Recent Comments