María Berrío, ‘Anemochory’, 2019

New York City is a buzzing city known for its love and support of art and culture. The city is now making up for lost time since the pandemic and celebrating life and the endurance of the human spirit. As the 10th Edition of Frieze New York opens today, Sophie Neuendorf tells us what she’s most looking forward to this week

Having lived in New York for most of my life, I have a soft spot for Frieze Art Fair. In fact, the entire “Frieze Week” is always an eye-opening, immersive experience. There’s even more energy in the city than usual, and it really heralds the beginning of Spring art season.

Opening on May 18, Frieze Art Fair will welcome visitors to The Shed on West 30th for the second year. It’s also Frieze NY’s 10th anniversary edition and the first under the stewardship of new director, Christine Messineo.

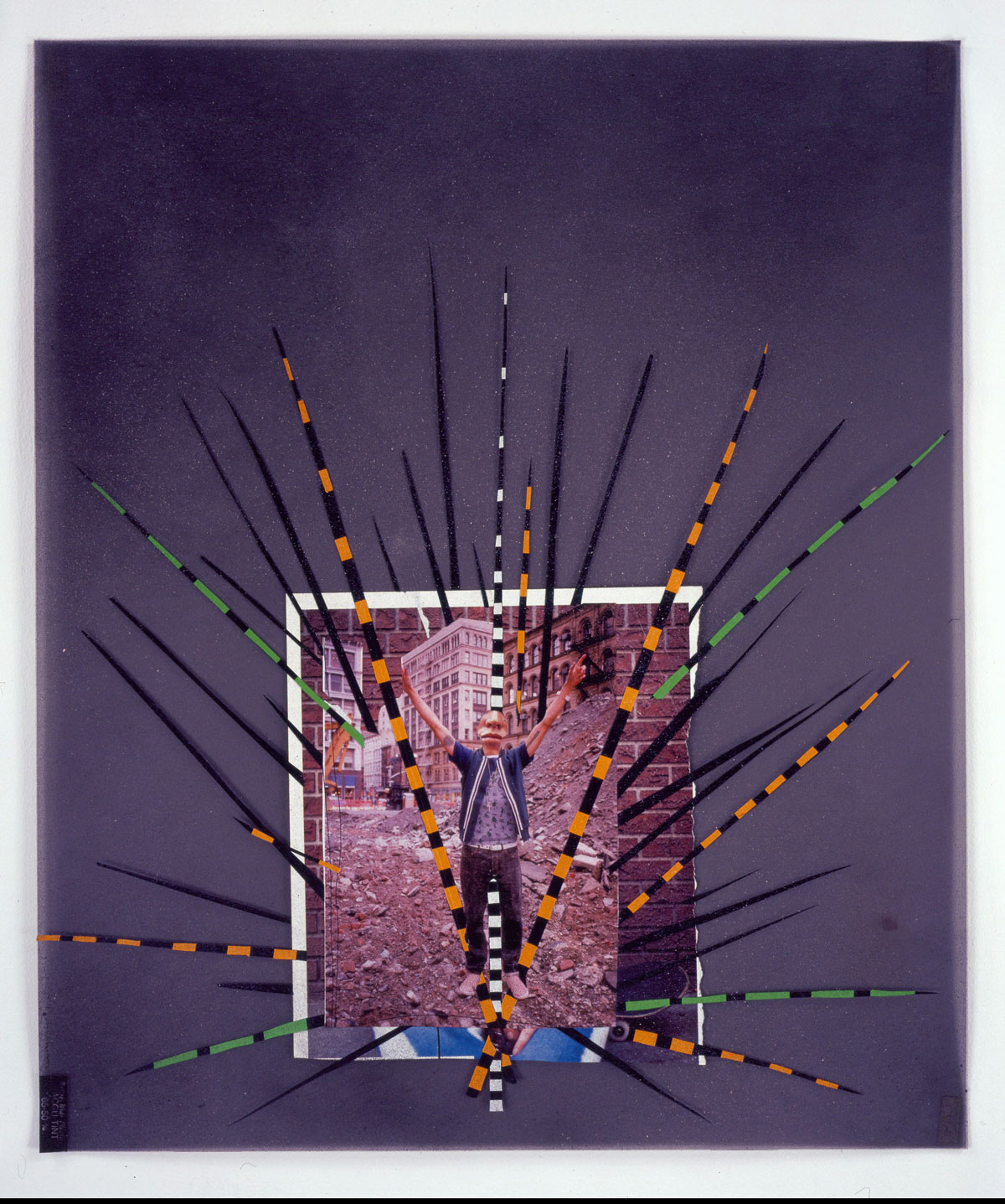

Performance shot of Aphrodite Navab from The Homeling, ‘Ink and Lipstick on Paper’, 2017. Aphrodite Navab is represented by A.I.R.

What I particularly enjoy about Frieze New York is its meticulous programming and marvellous events, with well-curated shows, gallery openings, and spotlights on up-and-coming artists. This year, in a touching tribute, Frieze is celebrating New York-based non-profit organisations that have also seen significant anniversaries over the past year. These include A.I.R., Artists Space, Electronic Arts Intermix and Printed Matter, Inc. Frieze New York will highlight and honour each organisation and celebrate their continued contribution to the New York cultural landscape.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

In an especially poignant tribute to current events, A.I.R., the nation’s first all-female artists co-op gallery, will respond to the seemingly imminent overthrow of the landmark court case Roe v. Wade with Trigger Planting, a map of U.S. states where abortion will likely be outlawed. Interestingly, it will be made with herbs traditionally linked to fertility and reproduction.

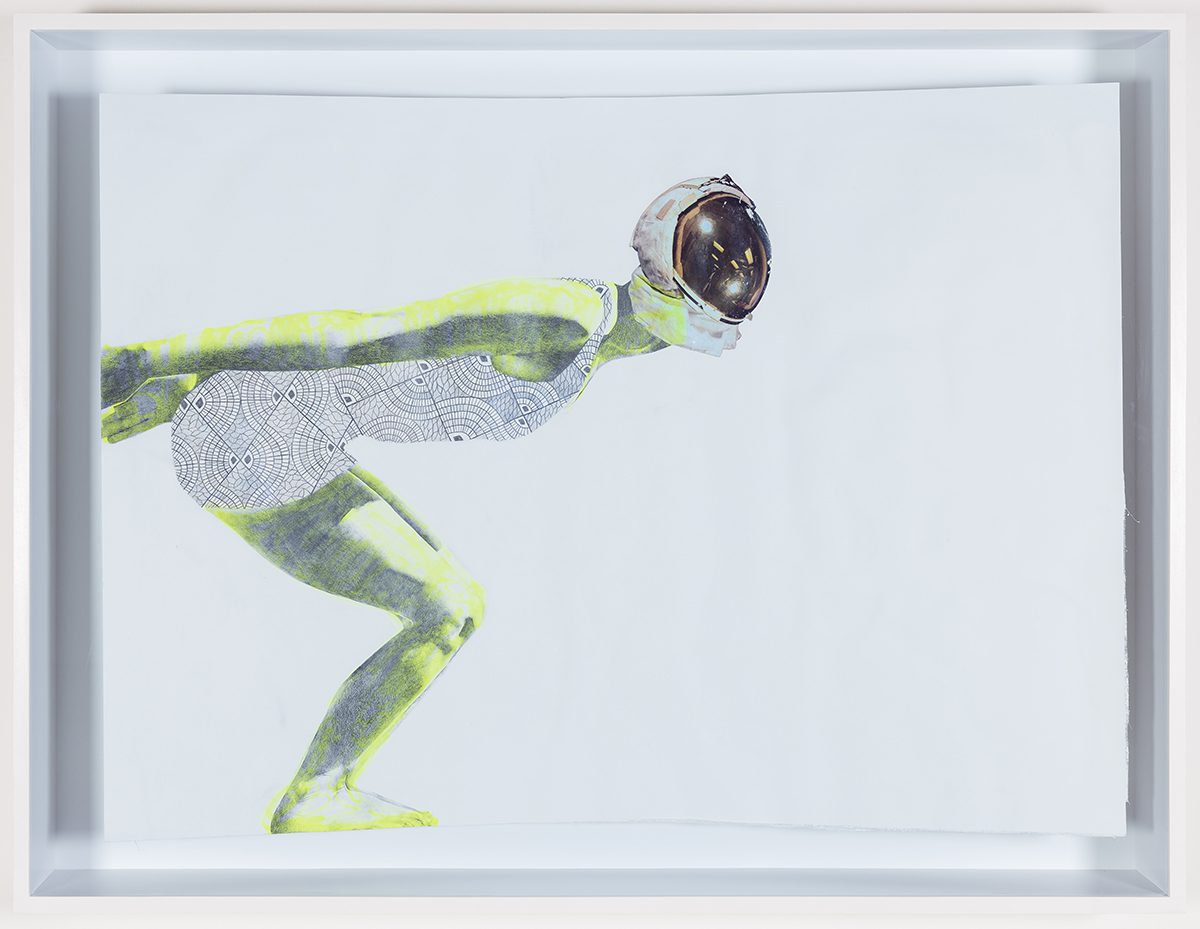

Baseera Khan, ‘Braidrage’, 2017-ongoing. Performance, duration variable. Photograph documenting performance at Participant Inc., New York, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Simone Subal Gallery, New York. © Baseera Khan. Photo by Maxim Ryazansky

According to Messineo, the participating organisations’ “support of emerging visual and performing artists, especially women, Black, and LGBTQ practitioners, reflects the spirit of many of the artists exhibited at this year’s fair.” Continuing that, “The mission of these organisations remains as urgent as when they were founded in the 1970s, and Frieze New York pays tribute to their creative lives.”

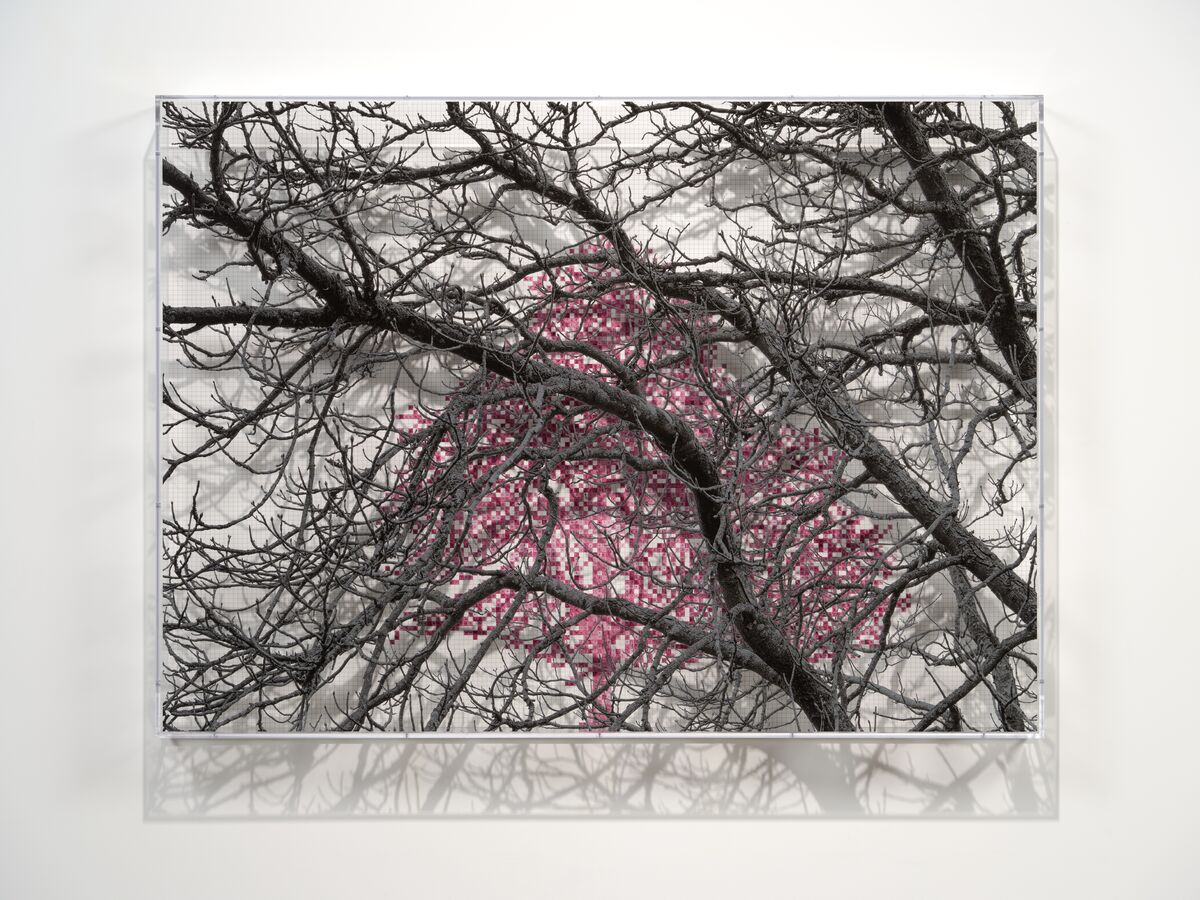

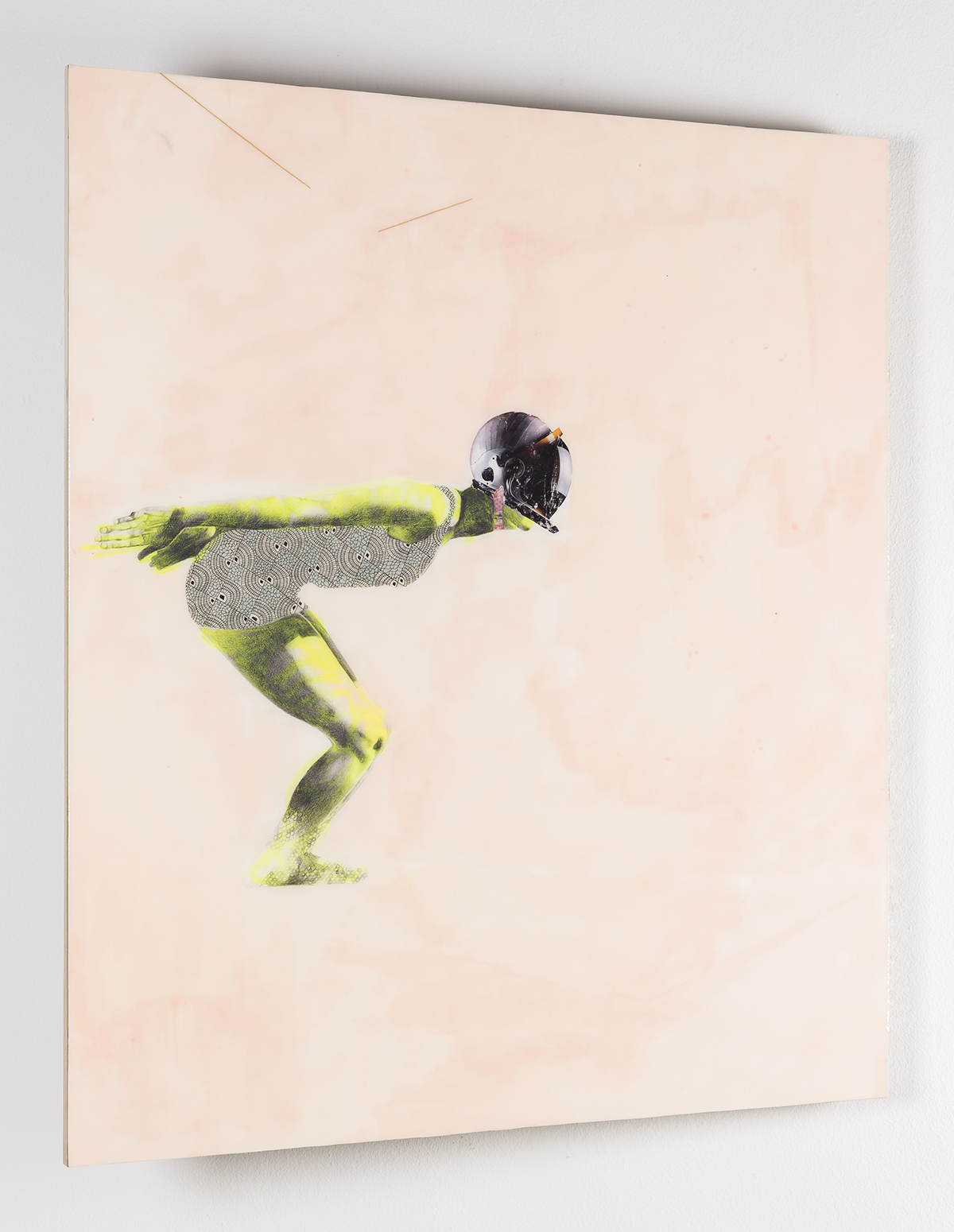

Charles Gaines, ‘Numbers and Trees: London Series 2, Tree #1, Blomfield Street 2022’. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth

With 65 galleries showing at the fair this year, it’s going to be tricky to select favourites. However, a few of my must-sees are Alice Neel and Tracey Emin at Xavier Hufkens; Maria Berrio at Victoria Miro (the proceeds of this work will support Unicef’s humanitarian response in Ukraine!); Luiz Roque and Solange Pessoa at Mendes Wood Gallery (both artists are showing at Biennale); and Charles Gaines at Hauser & Wirth.

Read more: Sophie Neuendorf’s Inside Guide To The Venice Biennale

One of my favourite fairs, Volta, is finally returning to New York after a few tumultuous years. Opening with 49 international galleries, it will now take over 548 West 22nd Street, most recently home to Hauser and Wirth but best-known as the longtime home of the Dia Foundation. In contrast to the blue-chip heavy-weights showing at Frieze, Volta caters to a middle market. I’m particularly looking forward to seeing their eclectic mix of galleries and artists, from Istanbul to Tokyo, Berlin and Lebanon.

VOLTA Art Fair. New York City. Photo: David Willems

Also returning after a three year hiatus, 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair is opening with presentations from 25 galleries. In a surprising departure from the usual locations they were previously in the west village and red hook), the fair is moving to Harlem this year, the city’s historic African American enclave. This is perhaps a tribute from a fair dedicated to art from Africa and the African diaspora. Look out for one of their special projects, an NFT collaboration with Christie’s.

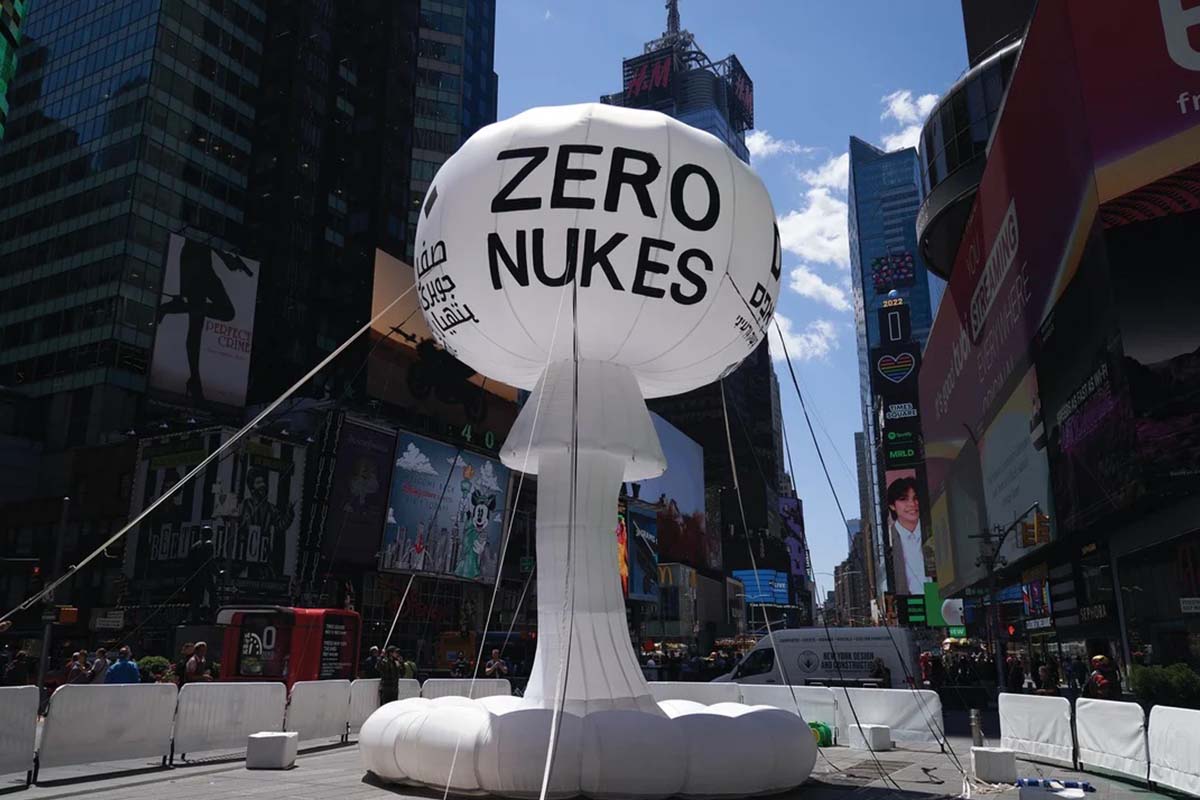

Amnesia Atómica, ‘Zero Nukes’

From an inflatable mushroom to the celebration of 20 chefs at the Brooklyn Museum, there’s a lot going outside the fairs. Apart from the Frick Collection, which is always worth a visit, not only for the collection but as an oasis of tranquility, I’ll be rushing to these exhibitions:

1. Amnesia Atómica NYC: Zero Nukes, at Times Square. This oversized, inflatable mushroom cloud sculpture by Mexican artist Pedro Reyes will spend the week in the heart of Times Square as part of an effort to raise awareness of the anti-nuclear movement.

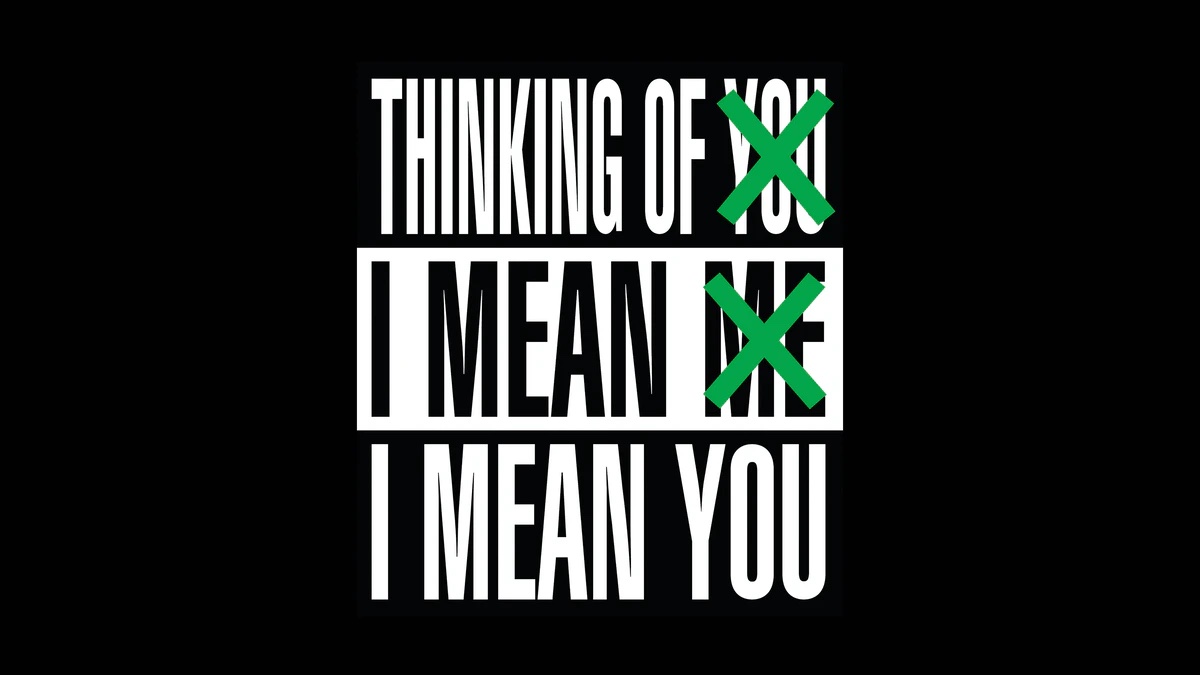

2. Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You. at MoMA, because Barbara Kruger is an icon and one of the most important artists of our time.

Barbara Kruger, ‘Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You.’

3. Baseera Khan: I Am an Archive at the Brooklyn Museum, which explores the lived experiences of people at the intersections of Muslim and American identities, both today and throughout history.

In this year’s Frieze Week, the art world seems especially sensitive to current events and taking the time to highlight internationally important socio-political issues, maximising the soft power of art and culture to affect positive change. In turbulent times, the art world can be a beacon of hope and strength.

Sant Ambroeus restaurant, New York

For those looking for lighter entertainment to mix it up, London-based luxury fashion retailer Matches, who’ve collaborated with Frieze London on several occasions, opened a pop up shop on 160 East 83rd Street. Take a break and browse the latest high-fashion summer collections as they celebrate Frieze Week in the city. Relax at Sant Ambreous in between and above all, enjoy the New York City energy.

Recent Comments