The Bryant Estate’s 13-acre vineyard, overlooking Lake Hennessey

Bettina Bryant, owner of California’s iconic Bryant Estate, is a wine-world legend. She is also a philanthropist, a significant art collector and cultural polymath, and an advocate of nature and biodiversity. Darius Sanai meets Bryant over a thoughtful dinner in Mayfair, and she, in turn, presents a first-person meditation on her life and work

Encountering Bettina Bryant for the first time, in a Mayfair restaurant, I would not have imagined that she was in the wine industry. Elegant, compact of movement, considered and thoughtful, Bryant has an academic poise. She is an art historian (she studied at Columbia University), a collector and a former dancer. If anything, I would have imagined she was an academic: there is a precision to the way she gives answers, the sign of a mind that does not indulge in irrelevant debate.

Matt Morris: A Cabernet Sauvignon grape seen as a heavenly body – Bryant grapes are harvested according to the lunar cycle.

But Bryant also owns one of the world’s wine legends. Lovers of California’s renowned Cabernet Sauvignon-based red wines, which are as acclaimed and sought after as the most celebrated of Bordeaux, know that her Bryant Estate is one of the region’s own “first-growths”, the equivalent of a Château Latour or Château Lafite. (Unlike France, California doesn’t have an official first-growth categorisation system, but everyone knows that Bryant would be one of them if it did.)

In that, though, there is heartbreak. It was her visionary husband Don Bryant who first established the reputation of Bryant Estate alongside the likes of Screaming Eagle and Harlan Estate, before succumbing to Alzheimer’s, with which he remains gravely ill.

Follow LUX on Instagram: @luxthemagazine

Bettina Bryant, the art historian, collector and former ballet dancer (she was mentored by Mikhail Baryshnikov at the American Ballet Theatre), unexpectedly took over the reins. Speaking with her, the conversation swoops between art, literature and, of course, wine. Although she is a born-and-bred American, Bryant’s parents had immigrated from Maienfeld, Switzerland – perhaps, coincidentally, the heart of that country’s fine wines.

The mineral-rich terroir

They were not in the wine industry: her father, Fridolin Sulser, was an acclaimed psychopharmacologist, an academic and scientific pioneer. You sense this in Bryant, in that precision and compactness of thought, which is common enough for scientists, but not so much for art collectors (this author does not know enough ballet dancers to comment on that side).

Since 2014, Bettina has been Proprietor and President of the winery, dedicating herself to maintaining the legacy established by her husband

Bryant has commissioned some fascinating and distinctive artists, including Ed Ruscha, to work with her winery: a particular favourite of mine is Sara Flores, a native artist from the Peruvian Amazon, whose art is at once deeply organic and somehow tightly graphic, rather like the mathematical forms of nature itself.

This commune with nature is important for Bryant. Her wines are biodynamic, and she has a scientist’s fascination for how natural cycles, and nature itself, interact with not just her vines, but with humans and our creativity. The wines themselves are creations of the utmost elegance and eloquence. Bryant Estate, the original legend, is deep, philosophical, somewhat Kantian in its uncompromising synthesis of nature.

A series of the renowned Bryant Family Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon

Bettina, a newer wine, has a lightness of being (is it autosuggestion to say it dances on the palate?), but also a persistence and gravitas. Bryant has also released a Chardonnay, a white wine of oceanic depth and character. All are made by Kathryn “KK” Carothers, her winemaker, a gentle soul with quiet wisdom and playful eyes who accompanies Bettina on many of her journeys around the world, like a family member. Enough from us.

Matt Morris. Weiferd Watts: The Cabernet Sauvignon vineyard

Bryant speaks about her life and her wines in her own words. We suggest a sip or two of Bettina, the wine, from an Ed Ruscha-designed magnum, as you drink them in.

A former dancer, Bettina’s creative story is interwoven with the wines, including the Bettina wine and this Bryant Estate logo

My journey to the helm of Bryant Estate was unexpectedly swift and accompanied by heartbreak. Six years after my arrival in Napa, my husband, Don, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and was unable to continue day-to-day oversight.

I am immensely grateful for the time we had to work together, for the opportunity to shadow him and ask questions. I also worked early on with oenologist Michel Rolland and helped create the Bettina wine. Establishing myself in the process sooner, the time Don and I shared at the vineyard and our travels to other wine estates was deeply informative and invaluable.

Untitled (Pei Kené 1, 2022), 2022, by Sara Flores

Don was extremely generous with me, opening iconic bottles from his cellar, dispensing advice on running the business, managing and mentoring people and, of course, always maintaining an uncompromising attitude when it comes to quality. For more than a decade, I have been putting his lessons to use as I work to evolve the winery.

Among the things I have implemented are:

Biodynamic farming: I am perhaps most excited to have transitioned the vineyard from organic to biodynamic farming. We use no pre-emergent herbicides and rely wholly on elemental forces, such as fire, to coordinate vegetative growth. We replaced plastic ties with biodegradable twine and, in following the lunar cycles, have discovered that vines pruned during the descending moon recover more successfully than on the ascending moon.

Swell (PICA PICA), Five Rings of Magpie Feathers, 2020, by Kate MccGwire

Already, improvements to vine physiology and vine stress resilience are demonstrable, particularly in recent drought years. We have never witnessed more soil vitality, and I firmly believe that this translates into more expressive and pure wine aromatics. Being in deep connection to the land and its gifts teaches us that we must be in right reciprocity in all aspects of life. For me, this holistic view encourages harmony, balance and beauty in the wines. Much of society has become too extractive. We must engage in good practices and be mindful in giving back to nature.

Education: I had wonderful mentors in my life and encourage my team to seek out opportunities for continued learning. I created two educational support programmes to encourage employees to pursue deeper learning, both in their chosen fields and in external areas of interest.

Philanthropy: I am passionate about philanthropy and have embraced four areas of support at the winery. First, the arts, emphasising arts education, creative learning and emotional healing through art. Second, the environment, spanning clean energy, climate action, conservation and environmental justice. Third, social impact, covering access to food, safe spaces, tribal support, job training and social justice.

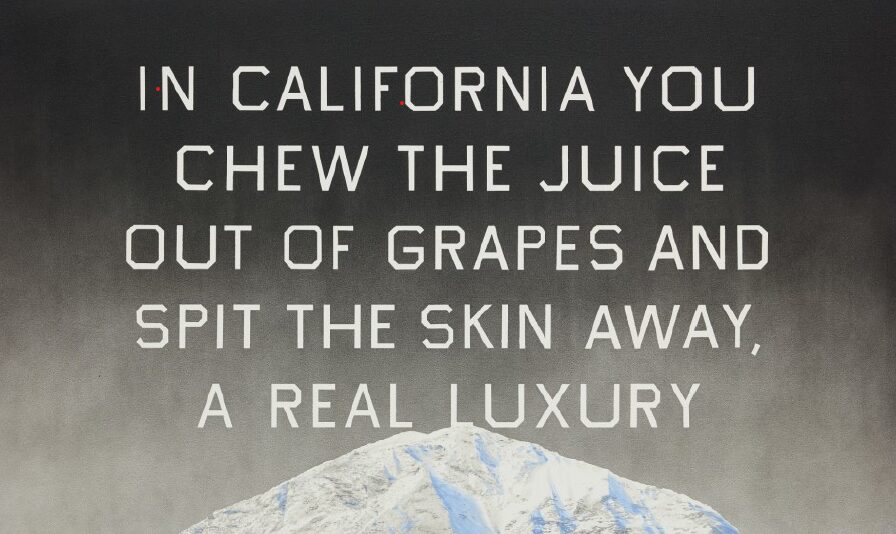

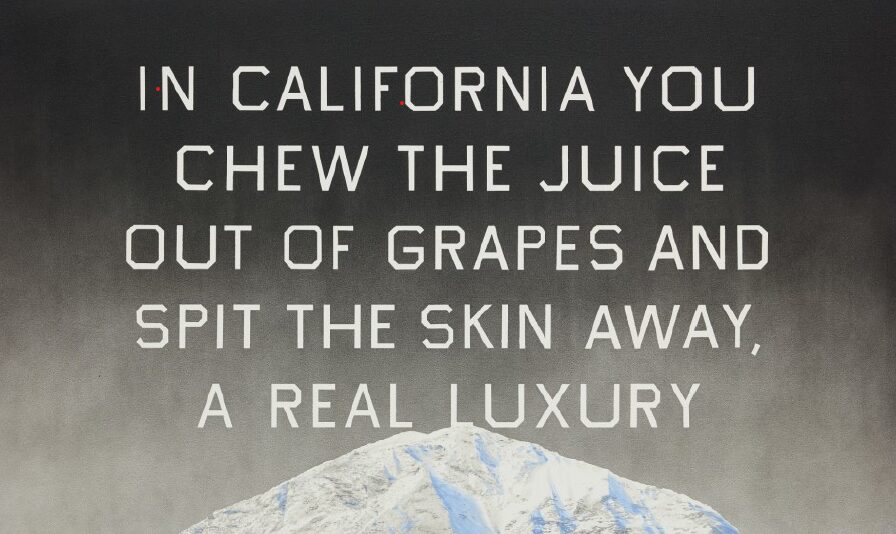

California Grape Skins, 2009, by Ed Ruscha

And fourth, mental health, encompassing research, advocacy and support.

Read more: Visiting Ferrari Trento: The sparkling wine of Formula 1

Immersive moments: I recently engaged the French architect Severine Tatangelo of Studio PCH to collaborate with me on a Tasting Room / Dining Pavilion at the vineyard. She has designed several hospitality projects, including Nobu properties in Malibu, Los Cabos, Santorini and Warsaw.

My desire is to holistically integrate wine, nature and art. I want to honour the vineyard, the wine and the talent behind the wine, and inspire people to be present, to connect with nature, light, music, or maybe even silence. The design approach will be sympathetic to and harmonious with the contours of the existing building and landscape, so much so that it practically disappears, and will utilise materials such as stone, wood, clay and natural fibres.

Supporting small producers: The Napa of today has many other pressing factors at play, compared to when Don founded Bryant Estate in the mid 1980s. Not only has the number of wineries increased exponentially, but we are facing unprecedented environmental factors and supply pressures.

One of my biggest observations over the nearly two decades that I’ve been involved is that many of the new players sweeping in to acquire smaller family-founded wineries seem to have little respect for the essence of what made these small producers special. Post acquisition, I find many of the wines unrecognisable. This was a big impetus to create Bryant Imports, to cast light on – and hopefully protect the stories of – these special producers.

Das Angebot (The Offering), 2016, by Neo Rauch

The art of wine: My background as a dancer and art historian informed my art collecting, and I approach winemaking with a similar lens. To cite music producer Rick Rubin, author of The Creative Act: A Way of Being, “Being an artist isn’t about your specific output, it’s about yourrelationship to the world”. For me, art and wine go hand in hand. The emanative, visceral power of visual art, music and architecture is no different for me than sharing a glass of wine with someone who understands that they are experiencing something ephemeral.

During the pandemic, I invited my friend Tom Campbell, Director of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, to join me and my winemaker in a lively Zoom discussion around art and wine. Tom and Renée Dreyfus, his Curator of Ancient Art and Interpretation, talked about objects and depictions of wine in the museum collections, and my winemaker, KK, examined the artistic process of winemaking.

In 2020, I released my first artistic wine collaboration with UK-based artist Rachel Dein. Using our vineyard cover-crop botanicals, she created a unique impression that we transferred to the interior of the wine box. Many of my collectors claim that this presentation box holds pride of place in their cellars. Art that demonstrates virtuosic ability, wrought by an artist’s own hand, has always compelled me.

I studied a lot of theory at university and, while that can be a very intoxicating and cerebral exercise, I find that I really appreciate the gesture of the human hand in a work of art. No wonder I appreciate the craft of winemaking! My husband and I collected a lot of minimalist and abstract art (Ellsworth Kelly, Brice Marden, Gerhard Richter, Richard Serra), and in 2015 I installed a particularly beautiful grouping in the Great Room of our St Helena home. In 2016, I acquired a wonderful Neo Rauch painting titled Das Angebot (The Offering), and I repositioned a Kelly to accommodate this work. The energy in the room instantly electrified.

The Rauch painting features a central, brightly hued female figure surrounded by male figure en grisaille. The female figure offers fire in her cupped hands, alongside a muscular hand digging its hand into the earth. With this installation, I realised an affinity for figurative work that clearly harkened from my time in dance.

I now realise that this painting was perhaps prophetic, as I lost my home in the 2020 fires that swept through the valley. Thankfully, my connection to the earth remains solid. During the Covid pandemic, I was inspired by how the environment benefitted.

Artist Rachel Dein’s impression of botanicals from the estate, which featured within a wine box

The waterways cleared, air quality improved, turtles were returning to their natural breeding patterns, and so on. I also discovered the astonishing foraged feather pieces of Kate MccGwire and commissioned a large concentric work from her.

My interest in the utilisation of natural materials in art also led me to the Peruvian painter Sara Flores, a 74-year-old Shipibo-Conibo artist, who sings to the trees before she extracts the bark to make her pigments. I find that so touching and am excited to support a documentary film on her life and work.

And Ed Ruscha [who designed the 10th-anniversary artwork for the Bettina bottle] was a dream to work with and very receptive to my ideas – a genuinely generous artist (and human being). It was a complete honour to work with him.

The vineyard is located in a moderate microclimate that fosters natural sugar development and a gradual ripening of the grapes

Tapping more deeply into my creativity and understanding the opportunity to learn and grow is one of the greatest gifts of life. One of my particular joys is supporting others on their learning and creative paths, whether encouraging my winemaker to source and craft our new Chardonnay, commissioning works by artists or evolving my new business venture supporting other small wine producers whose values resonate with my own.

On a more personal level, I am about to begin meditation and mentorship work with a Buddhist teacher. With art and wine and luxury, it is imperative that we recognise the gifts we have been given and treat them responsibly.

Art and beauty have such potential to be catalysts for positive change. I have always loved Gerhard Richter’s quote: “Art is the highest form of hope”. In these turbulent times, I feel more compelled than ever to create and deliver a wine and experience that resonates and inspires.

bryant.estate

Recent Comments