A sustainable blue economy is essential for the world’s future economic growth and environmental preservation

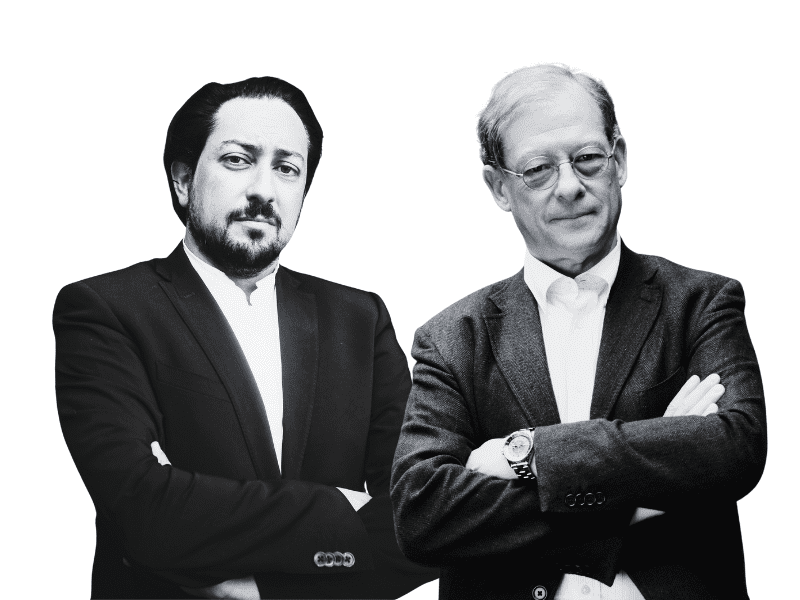

Markus Mueller, global head of ESG in the chief investment office at Deutsche Bank, has clear views on the transformation required to create a sustainable economic system. Meanwhile Jean-Baptiste Jouffray, of Stanford University and previously the Stockholm Resilience Centre, is a leading young thinker around the effects of our era on the oceans. LUX Editor-in-Chief Darius Sanai brings them together for a refreshing and thought-provoking conversation.

What happens when a leading economist with a strong understanding of science and a focus on the oceans, and a brilliant young ocean scientist with an interest in economics, get together? Fireworks, or at least one of the more interesting conversations to be had over Zoom.

I first introduced Markus, a good friend and at that point also a client of ours, and Jean-Baptiste, whose charm and perspective on the oceans and what needs to be done had always intrigued me, a year or so ago, and we decided a free-ranging chat about the economy, oceans, and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) would be compelling for our readers. So we came together again, over Zoom, and it was as engaging as I had hoped.

Markus is a thought-leading economist and also a realist; Jean-Baptiste is a brilliant thinker on the oceans but also knows sustainability is indelibly linked to economic systems. Let the conversation begin.

Follow LUX on instagram: luxthemagazine

Darius Sanai: Let me start with the question of shifting baselines. As I understand it, that means that people of a certain age or coming into awareness at a certain time have a different experience of the world than those who remember things 20, 30 years prior, in a world that’s rapidly changing.

Specifically when it comes to the environment and nature, although that could also include politics, economics, and everything else. As a basic example, a child today could thinks 40 degree summers and green winters in the Alps are “normal”. How important is this? Is it a universal negative? And how do we address it?

Markus Mueller: I think shifting baselines is something which fortunately makes humans and societies resilient. Because they automatically, through the shifting of baselines, adapt to the new reality which they have not seen unfolding.

Deutsche Bank’s Markus Müller says that nature-based solutions are a critical tool in creating a sustainable economic system

DS: Does it also make them complacent?

MM: This is a risk. It makes them complacent at the same time. There is a little bit of ambiguity. So, on the one side, I think it’s an important ingredient for social and economic development in the end because it makes us resilient in regards to changing environmental constitution and impacts on us.

But being not aware of this change makes us too complacent in the sense that we might run into a risk that something will further limit our development.

DS: Jean-Baptiste, can I ask you a variation of the same question? Last week, I watched a repeat of a TV show made in 2010, a murder mystery. The police detectives are standing outside the scene of the crime in the British countryside in summer.

And what struck me was that this frame was full of insects. And right now, 2024, just 14 years later, you wouldn’t see these insects. That’s a shifting baseline because a child born in 2010 would have no idea. That has to be a worry?

Jean-Baptiste Jouffray: Thanks, Darius. I think Markus knows how to trigger a debate because by pointing out how a shifting baseline is making us more resilient, he’s already triggered me. From an academic perspective, the shifting baseline syndrome is really well documented – it’s a whole theory, to explain change’s in the natural environment. And I wouldn’t have started by saying it makes us more resilient.

I would have argued that it makes the loss of resilience. One of the challenges of the shifting baseline is that, as you just pointed out with your example of the loss of biodiversity and insects in the British countryside, as generations come through, they are no longer accustomed to what things used to be.

Read more: Javad Marandi on investing and philanthropy

A very typical example in the coastal environment is fisheries in Florida, where you have historical photos of the catches of competition that takes place every year, about who is able to catch the biggest fish. And it’s a striking legacy of photos because you go back 70 years ago and you see the size of the fish and the first prize is this gigantic fish.

And the fishermen holding the fish and smiling with it. And as the years go by, the first prize goes to smaller and smaller fish. And it is almost an iconic illustration of the shifting baseline. For the people who come into that competition for the first time, that’s their biggest fish and that’s what the ecosystem has. There is no memory of what it used to be.

MM: And this is what I meant! And this is exactly the point why are we in a more biological devastating situation yet are still acting. Because we do not know how it was, we just know it in memory. It’s a nice story. I’m doing now the same with the younger generations.

When I was young, I went into church in April, and it was still snowing. It’s now warm. But I worry because I recognize it. But the new generations who just hear this from me do not worry about the situation in general.

JBJ: And that’s why I would argue that it may lead to inaction.

MM: Exactly. And complacency. It is a slippery slope because it shrinks our possibilities. It limits the room, which is already limited through physics and physical limitations.

DS: Can I now ask with regard to the situation you both outlined, just relating that to the question of effective change on climate and the blue economy? The idea of shifting baselines means, that I think we agree, that people are less incentivized to act because they don’t see change because it happened before they remember. Yet the change has happened.

How important is that emotive aspect in creating meaningful action? Or in fact, is that an irrelevance? Because the economic system and the regulatory system, which are not shaped by emotion, but by capitalism, are set up in a way that cannot enable this change. So is it really something that we shouldn’t be worrying about?

Read more: The future of philanthropy: AVPN South Asia Summit, Mumbai

JBJ: I would argue that it matters a lot and that emotions matter a lot and that it has been one of the battles that ocean conservation has had to face, when it comes to places in the ocean so remote like the deep sea, for instance, which has had to fight that battle for public awareness and public emotions.

How can people relate to a place that is pitch dark, 6,000 meters below the water and that no one has ever seen except a handful of people? More people used to have walked on the moon than actually dived at the very bottom of the Mariana Trench. So that aspect of emotion has been something really important in the context of ocean conservation.

Jean-Baptiste Jouffray says that shifting baselines, where new generations do not have the same perception of what environmental “normality” is, are a real and present issue. Photograph by Pelle T Nilsson/SPA

MM: In terms of economics, put simply we don’t need more money in order to deal with the situation. We just need to make the money flowing in the sustainable and economically viable projects if we factor in all costs. But this is not what we are currently doing. Hence, I fear that we run into situations where suddenly something is not anymore possible. And then we change. So you see this with the energy situation in Europe.

DS: On that note, Markus and Jean-Baptiste, so it’s now nine years since the SDGs were adopted. It’s coming up to four years since the Dasgupta report (which outlined the need for a new economics of biodiversity, to create systemic change in the sustainable future). How would you rate progress?

MM: I think in general, the progress is there. But this progress in the biodiversity and the ocean world has also been piggybacked by the climate change discussion, which is more immediate to us as more and more have to admit that they feel it.

Something which was there, which we didn’t know that it was there, and which then disappears, we don’t miss. This is one problem. The other problem is that it’s so local that it’s maybe not relevant for us in other places.

Read more: YCAB’S Veronica Colondam on bringing hope and change to Indonesia’s youth through social entrepreneurship

My last point is that we do not have a systemic discussion. We still have a very separate discussion. And this leads to the following problem. For example around SDG 4, education. Someone said to me recently, why is the SDG 4 so under-invested?

And for me, it’s clear, because if you do not have a labour market in a country which is able to absorb highly skilled people. Why should you invest in education, from a return capital perspective? So we need to think about developing a system which enables us also to generate the returns we need for societal prosperity in the end. It is not just as simple that we say, we stop here and all will be good. We also need to find an answer to what will the people get out of it to feed their families, to pursue their daily life. And if I develop education without having a functioning labour market, I will have a brain drain in the best case. In the worst case, I will have no investments in education.

JBJ: I think Markus made some really interesting points. Starting with how can we care about something we didn’t know existed.

Well, that really brings us back to the shifting baseline syndrome. And it’s interesting because, in a sense, that is one of the issues, right? So I’m glad we finally came to terms with that.

MM: But again, this is a risk. But it’s interesting that we are still able to survive in situations where something is not anymore there, which has been there before, right?

JBJ: Absolutely. No, no. And I’m half teasing you, half being serious here. But one of the embodiments of the shifting baseline syndrome is precisely that lack of caring, which might hinder progress. That’s one aspect.

To answer your question, Darius, yes, there is progress. But what we’re seeing, first and foremost, is progress in the vision rather than the impact. So in other words, we are living in an era of ambitious collective vision, but limited collective impact.

Oceans are at systemic risk from climate change. Photograph by Isabella Fergusson

I think the vision is one thing, and it’s great. That’s where we’ve seen countries coming together. That’s where we’ve seen multiple stakeholders coming together. That’s why there’s an increasing number of multi-stakeholder collaboration and voluntary commitments.

All those are articulating progress in the vision of what one should do. But the impacts do not follow. And I think if we look at metrics, we’re nowhere close to where we should be given the urgency of the situation.

The financial sector is not doing, what it should do. The private sector is not doing, what it should do. It doesn’t have the incentives to do so. And the governments and the regulators certainly are not levelling the playing field and doing what they should do.

We’re now within six years of the 2030 agenda and we are not on track to achieve any of the SDGs. The Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework may be superseding the SDGs and giving us an outlook for a post-2030 agenda with more ambitious targets.

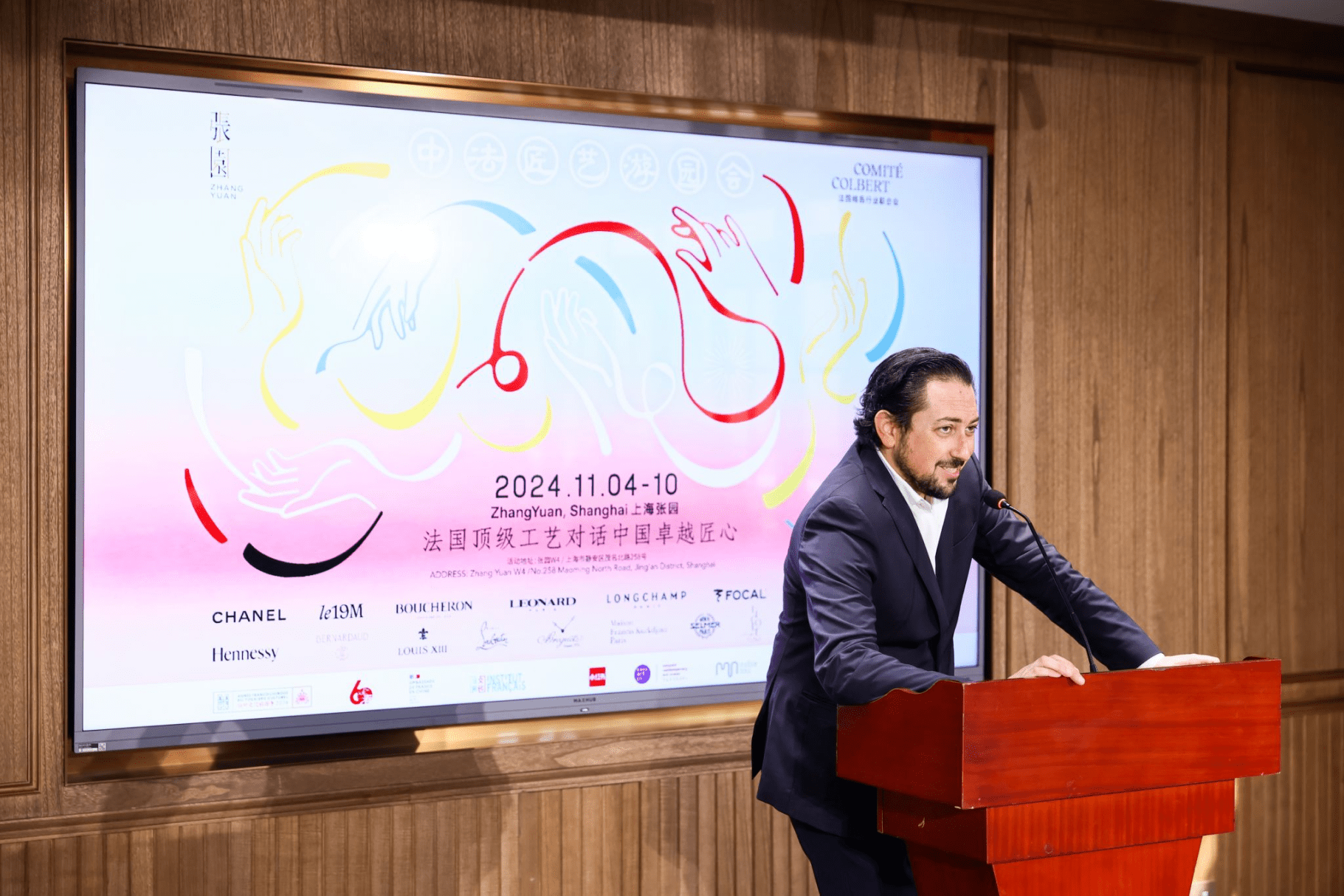

MM: I would agree. The other thing I wanted to add is that, compared for example to AI, the discussion about ESG is not liked. Sustainability is not liked. It’s seen as a paternalistic activity driven by regulators and governments.

Who wants to tell us how we should live, how economies should act? A regulatory approach for more sustainable development should be supportive, an approach which enables the economy, corporates, individuals to find solutions for their challenges… instead of telling them what they should not do.

Read more: Art collector Andrea Morante talks on artist Sassan Behnam-Bakhtiar

So these are two different sides of the same coin. To forbid something, but at the same time to enable something.

JBJ: I could argue that those two are not exclusive. And so I would tell Markus, maybe, you know, maybe regulators should enable while forbidding.

What I’m trying to get at here, and it’s something we have discussed in the context of the role of financiers in particular, is that I agree with Markus that there is a role for finance and financiers and financial institutions as enablers of sustainable futures and enablers of the blue economy.

The world’s oceans produce more than 2/3 of our oxygen and are essential for regulating our climate and biodiversity. Photograph by Isabella Fergusson

That brings us back to this dominant narrative in the blue economy of an ocean finance gap, right? Because, indeed, SDG 14 (about the oceans) is the least funded goal of all. So there is a gap in terms of ocean conservation.

There’s not enough investment going towards sustainable and equitable projects and into ocean conservation. In that sense, regulators, the public sector, the private sector and the financial institutions really have a role to play as enablers to unlock capital towards those projects.

DS: What needs to happen this year?

JBJ: Gosh, so many things. If I stick to the context of the ocean economy and the blue economy, one of the high-level processes that is ongoing is the ratification of the United Nations Agreement on Biodiversity beyond National Jurisdiction.

That’s often referred to as the High Seas Treaty or the BBNJ Treaty, which has been celebrated as a landmark of multilateralism. Countries have agreed on the treaty, which was a milestone, and now it needs 60 signatories to enter into force.

As of today, there are only four signatories. So if you ask me, by next year, which will also coincide with the 2025 UN Ocean Conference hosted by France and Costa Rica, then my hope would be that, this serves as a milestone for the treaty to enter into force. So what I’m hoping to see and what needs to happen is 56 countries between now and next summer to actually ratify the BBNJ Agreement.

DS: Thank you. And Markus?

MM: At COP 29 (in Baku in November) in a nutshell, collaboration, alignment and trust-building will be crucial ingredients to make progress on all of the aims. To deliver in the end a resilient and sustainable future. I think we have a lot on our plate and we need to work on it.

I think it’s a bad idea to put more on the list instead of working down the pile of things we already have on the list. I think this is a challenge of the COP that it’s not about adding on top all the time. It’s rather about getting the things done we already have on our list instead of putting new things on.

www.db.com

oceansolutions.stanford.edu

Recent Comments