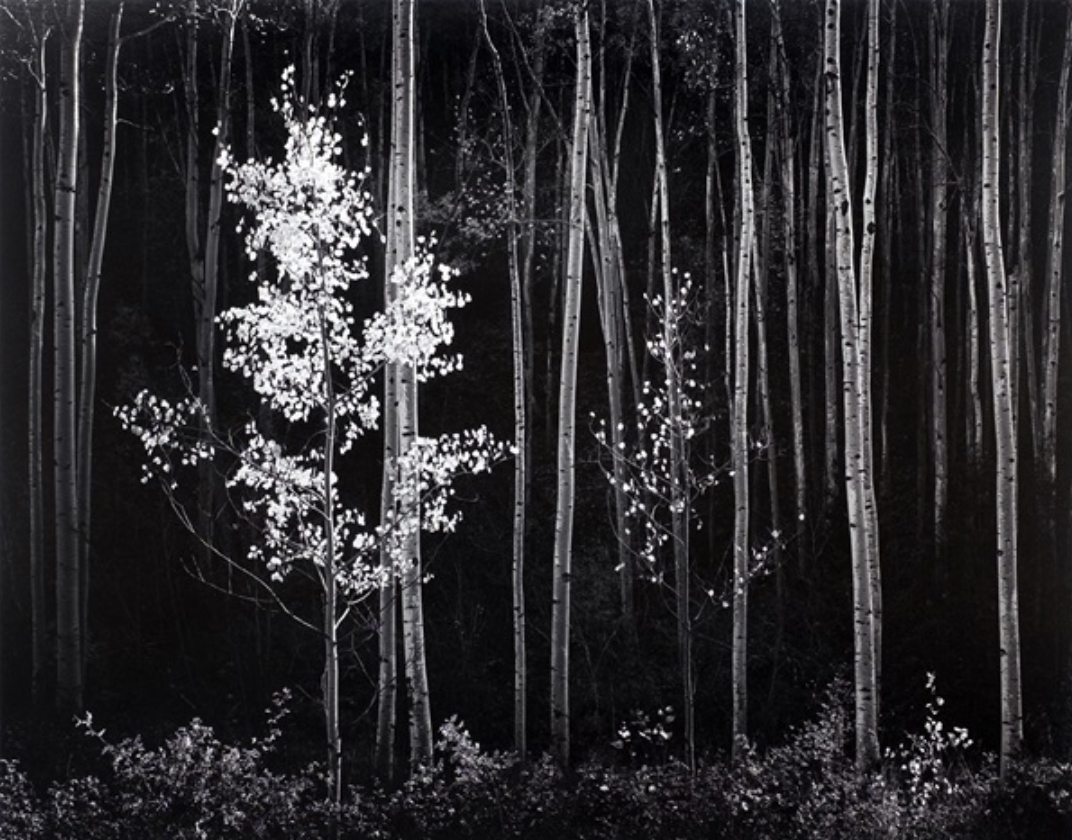

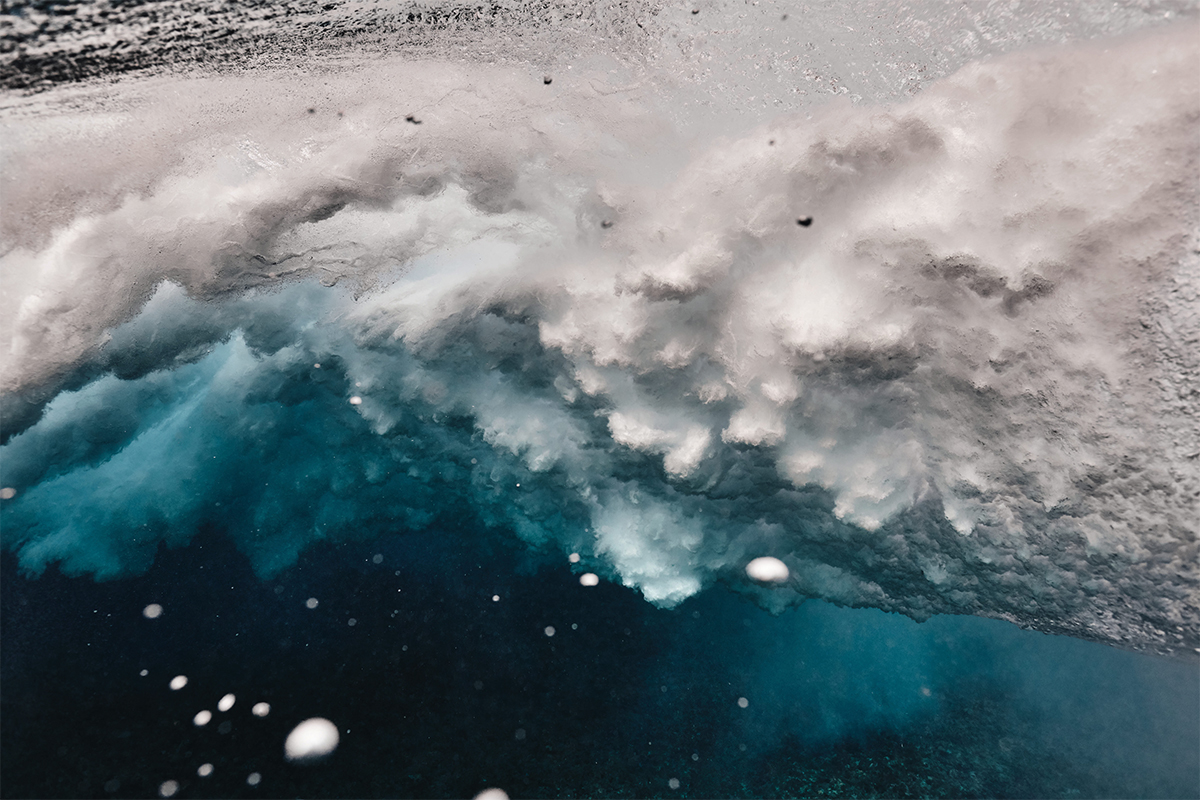

Art by Grace Crabtree

Genetically modified organisms have courted controversy since they were first developed. Mark Lynas’ new book explores the surprising extent to which politics has trumped science in the GMO debate, says Shannon Osaka

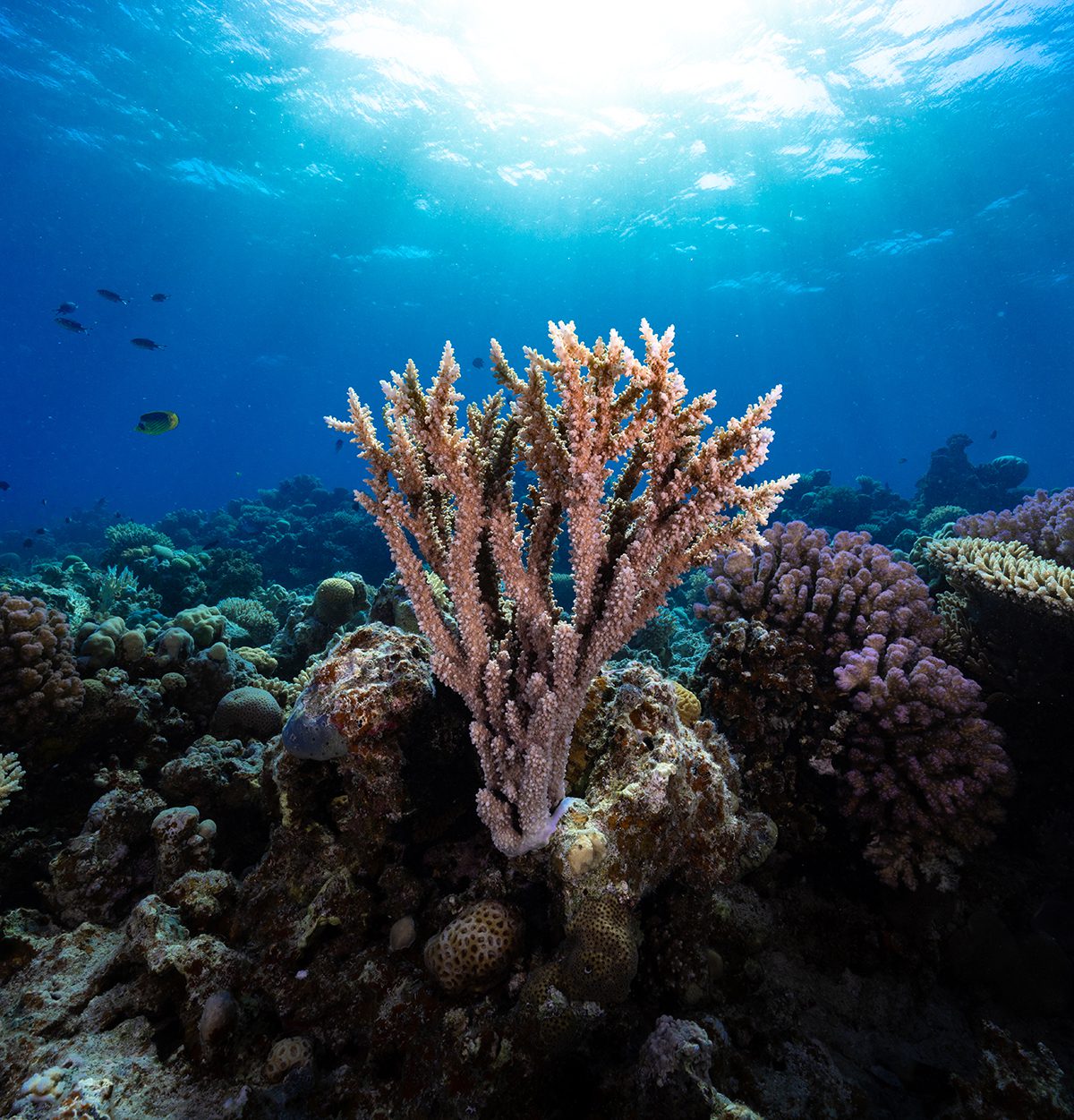

When Mark Lynas slouched onto the stage at the 2013 Oxford Farming Conference, he looked decidedly uncomfortable. After all, the British environmentalist and science writer — known for his well-researched and detailed books on climate change — was about to face his peers in a format best resembling a confession. ‘My lords, ladies, and gentlemen,’ he began. ‘For the record, here and upfront, I apologise for having spent several years ripping up GM crops.’

Lynas wasn’t speaking metaphorically. In the late 1990s, dressed in a black hoodie and clutching a machete, Lynas took part in ‘direct actions’ against geoengineering, in which he and his fellow activists dodged police and landowners to destroy GM crops. Their call to action was a milieu of anti-corporate sentiment, anti-capitalism, and resistance to the modification of nature. In advance of one early action, Lynas wrote on a flyer: ‘Huge corporations…are using genetics to engineer a corporate takeover of our entire food supply. There is still time to stop them.’

From the beginning, the producers of genetically modified organisms (GMOs or GMs for short) – including such unsavoury companies as the US-based Monsanto – have been embroiled in a war of attrition against environmental activists. Those ideologically opposed to genetic modification spent the late 90s and early 2000s planning protests and spreading misinformation about the dangers of the new crops. They called GMOs ‘Frankenfoods’. They demonised the scientists and researchers who developed them.

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

And they were overwhelmingly successful. In 2005, a Gallup poll found that a third of the US population believed that crops made with biotech posed ‘a serious health hazard to consumers’. By 2015, over half of the countries in the European Union, including Germany, France, and Italy, had enacted bans against the cultivation of GM crops. While GMOs are still grown today in the United States, their spread has been slowed or halted in Europe, Asia, and Africa.

To date, however, the deleterious effects of GMOs remain merely speculative. Ninety percent of scientists think that genetically modified foods are safe. The American Medical Association, the World Health Organization, the Royal Society of London, and many other science organisations worldwide have stated that GMOs are safe or, at the very least, not any more dangerous than organisms developed through conventional breeding methods.

It was the realisation that his position was not only unsupported by, but in fact the antithesis of, the scientific consensus that led Lynas to his emotional confession before the Oxford Farming Conference. It also led him to write Seeds of Science: Why We Got It So Wrong on GMOs (2018), a book that is at once memoir, polemic, and technology explainer; it is at times frustrating and at other times revelatory.

It is also timely. In an age that has been called ‘post-fact’ and ‘post-truth’, trust in science is on a decline amid a deluge of internet-spread misinformation, partisan politicking, and privately-funded denialism. A BBC documentary in 2010 declared that science was ‘under attack’ and the March for Science, founded last year in response to the inauguration of Donald Trump, attracted 100,000 participants in Washington, D.C. alone. On both sides of the Atlantic, doubt has spread on every scientific question from the veracity of anthropogenic climate change to the safety of vaccines.

Amid such conflict and uncertainty, Lynas’ recantation seems hopeful: a triumph of reason over emotion, of evidence over partisanship. But the real story is more complicated. As [Shawn] Otto explains in his lengthy and thorough The War on Science (2016), scientific reasons for supporting one position or another all too easily bleed into ideological ones – whether the issue is conservative opposition to climate change or liberal distrust of GMOs. Yes, Lynas changed his mind: but was he motivated by fact or ideology?

*

The story of GMOs begins with a misnomer. All organisms that we eat are, in one way or another, ‘genetically modified’. We have crossbred similar species of plants and animals to select for particular, idealised characteristics. That’s why carrots are orange, large, and sweet rather than small, white, and woody. That’s also why we have domesticated dogs that range in size and shape from the dachshund to the Great Dane.

But it can’t be denied that GMOs have an extra ick factor. Genetically modified organisms, in the sense that we use the word today, contain genes that have been extracted from some other, often completely unrelated, organism. Donor DNA which codes for a particular useful protein is removed and implanted into the recipient, imbuing it with the superpowers of (in the case of food) pest or herbicide resistance. This type of genetic engineering is cool, but also frightening. As Lynas said in his conference speech, ‘This absolutely was about deep-seated fears of scientific powers being used secretly for unnatural ends … We employed a lot of imagery about scientists in their labs, cackling demonically as they tinkered with the very building blocks of life.’ There’s something about modifying the genome itself that smacks of technological overreach.

Art by Grace Crabtree

It doesn’t help that GMOs are a poster child for the corporatisation of farming. Monsanto, a multinational conglomerate formerly based in St. Louis, Missouri, was one of the first companies to produce and commodify genetically engineered seeds. (Monsanto no longer exists as an independent entity: in June 2018, it finalised its sale to German chemical giant Bayer). Lynas traces how Monsanto engineers stumbled upon a highly potent, surprisingly safe herbicide called glyphosate, which the corporate eventually dubbed ‘Roundup’. Combined with a soybean genetically modified to resist glyphosate – aka the ‘Roundup Ready’ soybean – Monsanto could sell farmers seeds and herbicide simultaneously, ensuring a steady stream of profit.

Although the company touted its ethical bona fides at every opportunity, its business practises looked suspect. GM crops had promised to help the environment by removing the need for toxic herbicides and pesticides – but Monsanto’s first big biotech release required an herbicide: one that was produced only by Monsanto. The company had also pledged to reduce poverty in developing countries with its new crops. But it aggressively patented its products to lock out competitors, and seemed to seek a kind of monopolistic control over the world food system

Lynas and his fellow activists exploited this narrative to the best of their ability. Companies like Monsanto, they argued, were ‘playing God with DNA, and using customers as guinea pigs’. In one press release from 1997, Lynas claimed that under the biotech company ‘the natural world is being redesigned for private profit’. In these communications, multiple forms of GMO opposition were intertwined and blurred. Were Lynas and his colleagues worried that ingesting GMOs would cause illness, disease, or death? Were they reacting to the commodification of agriculture, food, and nature – a long-standing environmentalist raison d’etre? Or was it a purely philosophical opposition against human technological hubris?

The answer matters. The recent twist in Anglo-American politics has created an illusion that all science denial emerges from the right. Denial of climate change has become a near-fundamentalist belief from pro-industry conservatives, while right-leaning religious groups and conspiracy theorists contradict evolution and (in some bizarre cases), the fact that the earth is round.

But, as Otto argues, distrust of science is equal opportunity. It affects thinkers on the left and the right, when science conflicts with dominant ideologies. The anti-vaccine craze, beginning in England with now-discredited physician Andrew Wakefield, began as a movement of well-educated liberals who inherited the holistic health fad of the 1970s. Other historical leftist anti-science positions have included fear of fluoride in tap water, or suspicion that mobile phones and microwaves can cause cancer.

One of the mysteries of GMO opposition, however, is how the same left-wing environmentalists who espouse a 97% scientific consensus on climate change ignore – or even criticise – the similar consensus on the safety of genetically engineered foods.

Read more: Inside one of the world’s most exclusive business networks

Lynas was once one of them. Lacking a scientific background and propelled by green values, he wrote blithely in the 90s about the dangers of GM crops, with little empirical evidence beyond anecdotes shared among eco-advocacy groups. But over the next decade his focus changed. Inspired by what he saw as rampant rejection of global warming science (he once pied climate denier Bjørn Lomborg in the face during a book tour), Lynas started pouring over the research on climate change. He wrote two popular books explaining climate science: Six Degrees and High Tide.

In 2008, shortly after winning a science book prize for Six Degrees, he was asked by The Guardian to write an op-ed on GMOs. He was startled to find that he couldn’t locate any legitimate peer-reviewed sources to back up his usual claims that genetically modified crops could contaminate local environments, or that they led to the use of more hazardous chemicals in farming. ‘Facts are stubborn things,’ John Adams once wrote, and Lynas, overwhelmed, felt he was at a crossroads: all his environmentalist colleagues opposed GMOs. ‘I could betray my friends, or I could betray my conscience,’ he writes. ‘Which would it be?’

*

In the end, Lynas prioritised his conscience. In the first half of Seeds of Science, he attempts to debunk every wrongheaded GMO belief he ever harboured, from claims that GM crops cause environmental devastation to the moral culpability of Monsanto. In some places, such as in his polemic against ‘fake news’ peddled by the environmental movement, his interventions are long overdue. In 2008, news outlets widely reported that thousands of Indian farmers had committed suicide because they couldn’t afford to pay Monsanto for genetically-engineered cotton seeds. The story was pushed by Vandana Shiva, a high-profile Indian activist who has called GMOs a form of ‘food totalitarianism’ and referred to the introduction of insect-resistant Bt cotton into the state of Maharashtra as a ‘genocide’.

But, as Lynas points out, all available evidence shows that suicides among Indian farmers are no higher than other countries in the developed or developing world – including Scotland and France. Journalists, including Lynas himself and New Yorker correspondent Michael Specter, travelled to Maharashtra and found no evidence of the massive suicide waves Shiva and anti-GMO campaigners pointed to. Lynas writes, ‘The Indian farmer suicide story is a myth, built … by those like Vandana Shiva with an ideological axe to grind and little concern about the true facts.’

In other places, however, Lynas seems blinded by his own enthusiasm. Eager as he is to debunk GMO fears, he conflates the connection between GMOs and health – a question that science can answer – with more philosophical oppositions. We can think GMOs are safe to eat, but still question whether humans should be modifying genomes in the first place. We can believe GM crops are safe for the environment, and still critique Monsanto’s patenting process and its monopolisation of the global food supply. When Lynas writes a chapter lionising the history of Monsanto, he sounds less like a rational man of science, and more like a man who has traded one ideology for another.

And while science itself may not be ideological, its interpretation, and the public’s belief in its findings, certainly is. Otto argues that the role of values and ideology in scientific trust has plagued communication (and democracy) for decades. The British philosopher and scientist Francis Bacon put it best when he wrote, in 1620: ‘…What a man had rather were true he more readily believes. Therefore he rejects difficult things from impatience of research … [and] things not commonly believed, out of deference to the opinion of the vulgar. Numberless, in short, are the ways, and sometimes imperceptible, in which the affections colour and infect the understanding.’

While Lynas initially wanted to believe that his change of heart was based on cold, hard, scientific facts, modern psychology has proven the opposite. Science communication is often based on an ‘information deficit model’; if only the public were more informed, scientists argue, they would accept findings from anthropogenic climate change to the safety of GMOs.

But the truth is more complicated. For example, on the issue of climate change, studies have found that greater scientific literacy actually increases polarisation. According to a 2008 Pew Research Center Study, highly-educated conservatives in the US are less likely to believe in climate change than their less-educated counterparts. Otto attributes this to an educational model overly focused on critique, combined with never-before-seen political polarisation. He writes, grimly: ‘We are inculcating the attitude of scepticism without teaching the skills of evidence gathering and critical thinking needed to discern what is likely true.’

Read more: Knight Frank’s Chairman Alistair Elliott on research and tech

The problem is that in the human mind, values run hotter than evidence. Essential knee-jerk moralisms (like opposition to sexual taboos) and partisan ideologies, whether pro-corporate or anti-establishment, take centre stage in the battle for our minds. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt, author of The Righteous Mind (2012), argues that when faced by evidence contradicting a deeply-held belief, people ‘reason’, but not to find truth. Instead, they reason to support their emotional reactions. ‘If you ask people to believe something that violates their intuitions, they will devote their efforts to finding an escape hatch – a reason to doubt your argument or conclusion,’ Haidt writes. ‘They will almost always succeed.’

When it comes to the politics of science, a set of ideologies divide the public on controversies. Otto, with a chart that resembles a tuning fork, separates science sceptics into two broad camps. On one side, an odd couple of ‘old industry’ (oil, chemical, and agricultural companies) and ‘old religion’ have banded together to form right-wing anti-science. Otto calls it a ‘marriage of convenience’. ‘The fundamentalists needed access and legitimacy and the business interests needed passionate foot soldiers,’ he writes. Together, this right-wing group doubts the science of climate change, evolution, and reproductive health. On the other side, pro-environment liberals have joined with anti-corporate activists to question mainstream medicine, the safety of vaccines, and worry about the deleterious effects of GMOs.

This is certainly an oversimplification of a problem that is more granular than Otto lets on. Anti-science doesn’t split so neatly along partisan divides. (For example, while liberals tend to be the most active anti-GMO activists, many conservatives are suspicious of GM crops as well.) But his premise helps to unlock the puzzle of why climate change believers like Lynas are often also GMO sceptics. For an environmentalist, belief in science is not the tantamount value, but rather belief in preserving a particular vision of ‘nature’, one that is external to society but vulnerable to human influence. Within this worldview, anthropogenic climate change makes sense, but so do the dangers of genetic engineering. When value-centred beliefs clash with science – and with an increasingly entertainment-focused news media that, as Otto argues, is no longer a ‘marketplace of ideas’ but a ‘marketplace of emotion’ – consensus and evidence take a backseat to more heartfelt beliefs.

That’s a deeply troubling sign for a democratic society. Otto believes that science is essentially anti-authoritarian, that it relentlessly challenges received wisdom through a rigorous system of peer-review and hypothesis testing. What are we to do, then, when research shows that both the left and the right are unable to set ideology aside when facing scientific questions?

In the final few chapters of Seeds of Science, Lynas begins to understand the real reasons behind his change of heart. His polemic against anti-GMO activists gives way to a sincere exposition on the role of partisanship in science belief. His recantation came, he notes, on the heels of his acceptance into a community of scientists and science journalists, and thus into a new ideology (albeit one that placed science first). ‘Deep down,’ he writes, ‘I probably cared less about the actual truth than I did about my reputation for truth within my new scientific tribe … It wasn’t so much that I changed my mind, in other words. It was that I changed my tribe.’ It’s a dark takeaway from a book ostensibly written about the importance of facts and evidence.

Read more: A journey to the Kimberley with Geoffrey Kent

There are still reasons to oppose GMOs. One of Lynas’ friends, the Oxford-based environmental journalist George Monbiot, believes that the consensus that GMOs are safe changes little about the movement against them. ‘For me, it was all about corporate power, patenting, control, scale and dispossession,’ Monbiot told Lynas. In short, many of the villains countered by the environmental movement. Monbiot thus understands what Lynas initially ignored. Science can tell us about risks, benefits, and safety, but the decision about whether to genetically modify organisms (or, for example, whether to geo-engineer the climate to prevent catastrophic climate change), is a social and political one. It can only be made through use of all-too-human values and deliberation.

What is needed, then, is science as a platform, a foundation on which politics can be built. ‘Wherever the people are well informed they can be trusted with their own government,’ Thomas Jefferson wrote in a letter in 1789. At the end of his book, in a section optimistically titled ‘Winning the War’, Otto suggests science debates, a scientific code of ethics, journalistic standards for science coverage, and much more. He is a cheerleader for an evidence-based democratic society.

In the ‘post-truth’ era, where expertise is scoffed at and fact held in disdain, Otto’s scientific city on a hill seems a long way off. Humans that we are, we prefer narrative to evidence, linear stories to complex truths. We accept science when it aligns with our worldview; we doubt it if it does not. But, despite his flaws, Lynas represents the faint hope that under the right conditions we can change our minds. That, over time, the stubbornness of fact can – and might – outweigh the obstinance of ideology.

Shannon Osaka is a postgraduate student in geography at Worcester College, University of Oxford. She writes about technology, science, and climate change.

Aino Grapin is CEO of Winch Design, an international design studio for luxury planes, homes and most famously, yachts. Here, Grapin speaks to Samantha Welsh about the increased focus on sustainability in yacht design and the special requests of next generation yacht owners

Aino Grapin is CEO of Winch Design, an international design studio for luxury planes, homes and most famously, yachts. Here, Grapin speaks to Samantha Welsh about the increased focus on sustainability in yacht design and the special requests of next generation yacht owners

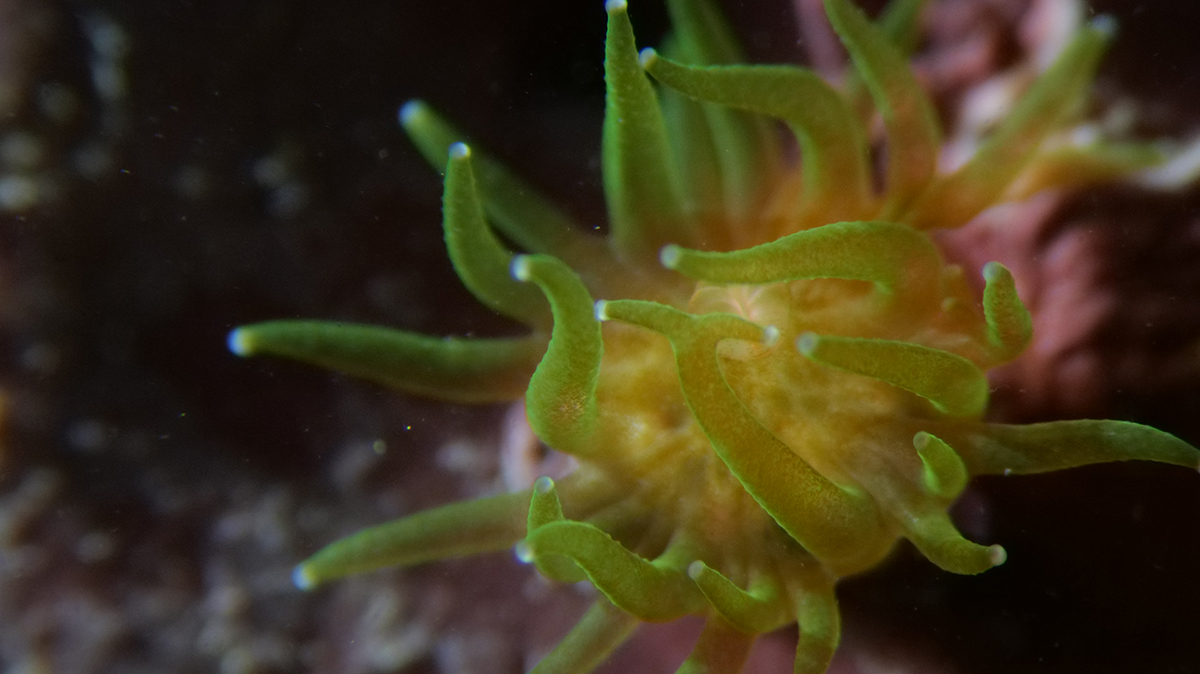

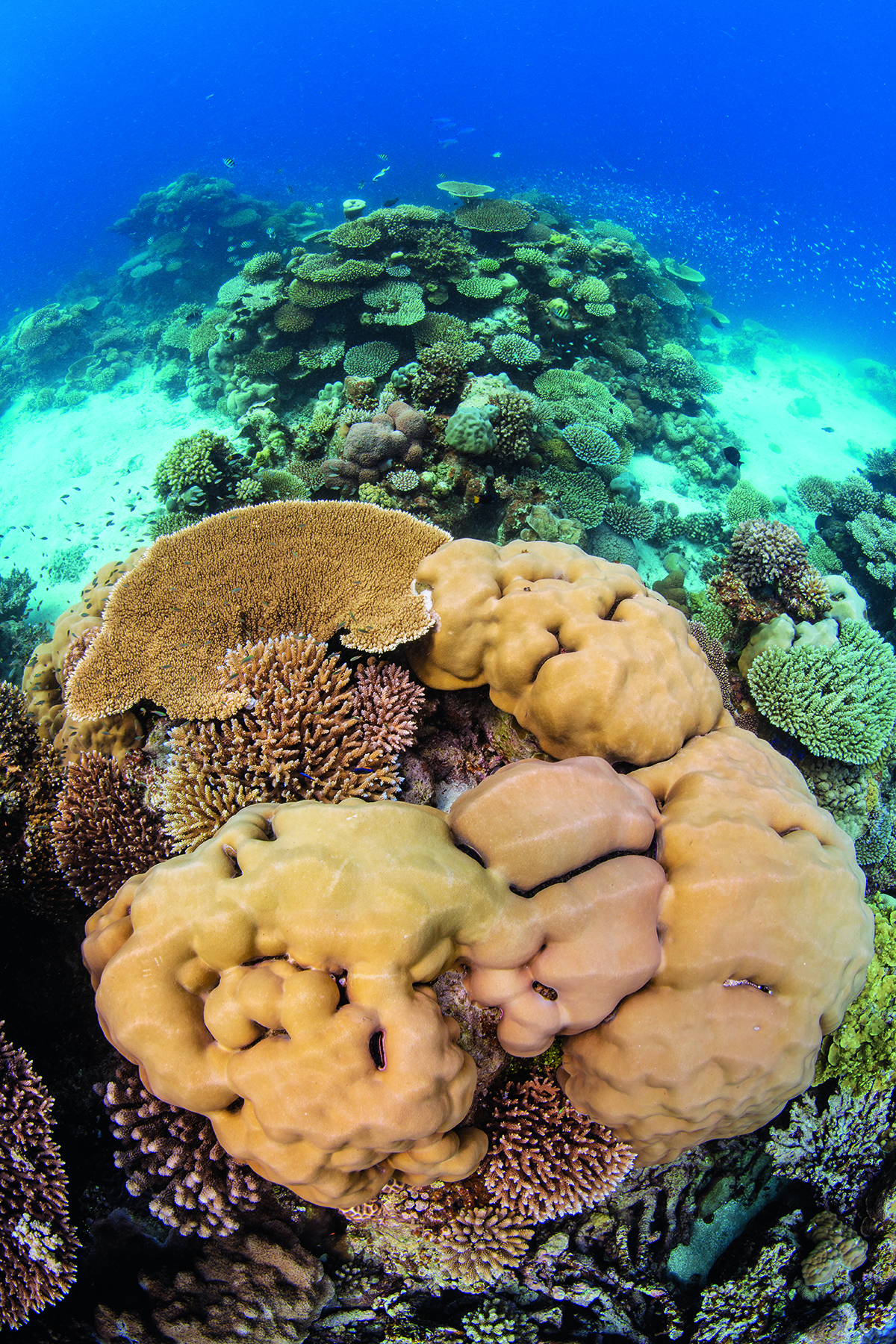

Can we put a price tag on nature? Valuing the carbon services of plants and animals is essential to bridging the gap between finance and conservation, says Professor Connel Fullenkamp, the leading academic working at the intersection of science and economics. Here, Fullenkamp speaks to LUX about the importance of engaging capital markets in biodiversity financing, and why necessity is the mother of invention

Can we put a price tag on nature? Valuing the carbon services of plants and animals is essential to bridging the gap between finance and conservation, says Professor Connel Fullenkamp, the leading academic working at the intersection of science and economics. Here, Fullenkamp speaks to LUX about the importance of engaging capital markets in biodiversity financing, and why necessity is the mother of invention

Jennifer Anderson, Co-Head of Sustainable Investment & ESG at Lazard Asset Management, speaks to LUX Contributing Editor, Samantha Welsh, about the history of her career, the changes in the ESG investment landscape over that time, and offers an insight into why she thinks the industry is at an important inflection point

Jennifer Anderson, Co-Head of Sustainable Investment & ESG at Lazard Asset Management, speaks to LUX Contributing Editor, Samantha Welsh, about the history of her career, the changes in the ESG investment landscape over that time, and offers an insight into why she thinks the industry is at an important inflection point

1. What inspired you to become a photographer, particularly in the polar regions?

1. What inspired you to become a photographer, particularly in the polar regions?