Seaview Seagrass, Solent, Isle of Wight, UK, image by photographer and marine biologist Theo Vickers. © Theo Vickers

As sea levels rise due to global warming, there are tremendous challenges for the environment, coastal communities and global supply chains. Mark Rowe reports and discovers ideas, initiatives and infrastructure measures to help stem the tide

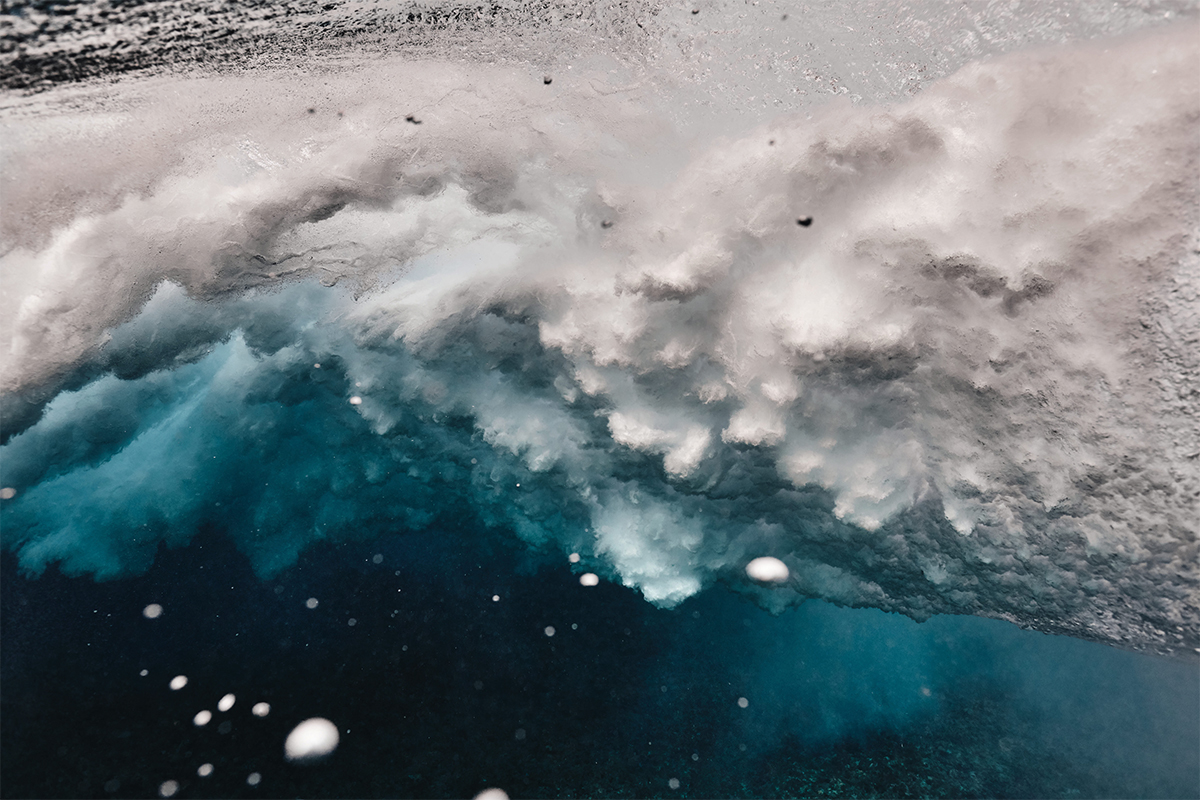

The sea is on the rise. All around the world, over the past 100 years, sea levels have risen by up to 25cm. And they are expected to rise by a further one metre in the next 80 years. The main driver of this increase is climate change, caused by humans pumping carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere.

This is driving sea-level rise through one reason everyone is aware of: melting ice bodies like glaciers and polar ice caps. What is less evident is that, even if all the permanent ice in the world were to melt, oceans would continue to rise as long as temperatures did, due to the physics of thermal expansion: warm water occupies more volume.

Dr Joanne Williams

“We can’t reverse what has already happened,” says Dr Joanne Williams of the UK’s National Oceanography Centre. Science, in the form of thermal lags, means sea-level rises are inexorable. Water warms slowly, so, due to deep ocean heat uptake, sea levels will rise for centuries, whatever we do. “The heat is already in the ocean, the rises are locked in,” Williams continues. “But if we act now, it costs less in the long term and we can plan without having to rush. It’s easier to adapt.”

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

In a 2021 report, “Coastlines in Crisis”, by Deutsche Bank Private Bank’s Markus Müller, ESG Chief Investment Officer, and Daniel Sacco, Investment Officer, the authors cautioned that “rising sea levels will put coastal populations and critical economic assets under increasing stress… substantial population displacement is not an unlikely scenario”. These are not abstract observations, and they highlight the challenges, including the human cost.

Dr Philipp Rode

Most of the world’s populations live by water. Around one in 10 of us live less than 10 metres above sea level and 70 per cent of the world’s largest cities are in low-lying coastal areas. Roughly 40 per cent of the US population lives in coastal cities. So communities, as well as their infrastructure, trade and buildings, both residential and commercial, are all at risk, making the adoption of adaptation planning even more of a priority. As Dr Philipp Rode, Executive Director of LSE Cities, puts it, “How sub-Saharan African cities will cope is very unclear. But the story of people being forced to move because it is too risky and too expensive to live there any more is one we will hear more and more.”

“The ways in which people are vulnerable varies,” says Williams. She cites Bangladesh, where a one-metre rise would shrink the country by one-third. “Bangladeshi people are used to flooding, but in the future it will happen more often, go further upriver and affect more farmland.” Much of the farming hinterland near Williams’s own city, Liverpool, in the UK, is at coastal level. “Not a lot of people live there,” she says, “but that’s a lot of food production at risk.”

It is apparent, then, that threats from sea-level rise affect more even than coastal ecosystems and coastal communities. They affect everyone through global economics in terms of agriculture, infrastructure, real estate, tourism and global trade. And all this affects the Global North as well as the Global South, the Netherlands as well as the Maldives.

This is because critical national infrastructure, most obviously ports, but also electricity and nuclear power stations, electricity cables, and gas and sewage pipes, are often located on the coasts. Twelve of the biggest US airports are built on coastal areas, and nearly one-third of US GDP relied on the coastal economy, employing almost 55 million people in 2016. It is estimated that 20 per cent of global GDP could be threatened by coastal flooding by the end of the century. Our seas handle 90 per cent of global trade and that means if ports get battered, then cargo – from plastic toys to grain consignments – will get tangled up with knock-on effects.

An Island’s Wild Seas, the Needles, Isle of Wight, UK, image by photographer and marine biologist Theo Vickers. © Theo Vickers

In the Global South, particularly, effects on sectors such as agriculture and tourism will be especially disruptive, as developing countries are most reliant on them. Saltwater inundation from flooding contaminates freshwater aquifers, making agriculture difficult, threatening food supply and making water no longer potable. That spells trouble for the people of Suriname, where almost three-quarters of the population lives five metres below sea level and most of its fertile agricultural land lies on the coastal plain. The Maldives’ highest point is just two metres above sea level, and, while it performs well compared to its small island peers, tourism accounts for almost one-third of its economy, making its people extremely vulnerable to rising sea-level shocks.

“Rising seas will not see cities sink slowly, millimetre by millimetre beneath the waves. Instead, changes are complex and abrupt,” says Rode. “Sea-level rises make other things worse. If you get a combination of flash floods, storm surges, high winds and high tides, the peak height of impacts will hit places harder. The higher sea levels are, the harder it is to get floodwater from heavy rain out of a city.”

Society does not have a great track record of awareness, let alone action, when small communities, or those from the Global South, are involved. Barranquilla is the fourth largest city in Colombia, with a population of 2.4 million. Located next to the Magdalena River, near the Caribbean Sea, it is a major port. But because of mismanagement and lack of investment in water infrastructure – it has no rainwater drainage systems, for example – it is highly vulnerable to floods and landslides. When the city floods, and it does, the roads turn into dangerous, fast- flowing rivers, sweeping away cars – and people. Sea-level rise is set to compound the situation, and while there is a push for legislation and some agreement to avoid disaster, there is no clear plan, resulting in stressed infrastructure, increased food shortages and poor, often Afro-Colombian communities, displaced to informal slums.

While the residents of Barranquilla still wait for change, the Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System was created in New Orleans right after the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. It is the most costly flood-control system on earth and one of the biggest public-works projects in US history. Governments around the world are becoming increasingly conscious of the risks of sea-level rise and are progressively implementing adaptation measures. Shanghai’s authorities place a high value on these because, by 2050, the city is predicted to endure floods and rainfall 20 per cent higher than the global average. To lessen its vulnerability to rising sea levels, the city has built 520 kilometres of defensive seawalls. The OECD warns against complacency, however. Solutions are out there, but they will need to come hand in hand with the regulation and business climate that allows them to become viable commercially.

Guy Michaels

Grey or technological solutions are often the direct go-to approach. London, which is estimated to have a water level increase of up to two metres in a low-emissions scenario, has its retractable barrier system, begun in 1974 and in operation since 1982. “And London can always get the Thames Barrier to do a bit more lifting,” says Guy Michaels, Associate Professor of Economics at the LSE’s Department of Economics. “In New York, which is 10 metres above sea level, you can think of ways to potentially close off the harbour.”

Tokyo created a spectacular solution in 2006. The G-Cans flood project is a huge cathedral-like underground cavern supported by 59 towering pillars. Permeable surfaces and a network of pipes divert floodwaters to a reservoir, before being slowly released to the Edo river. The price tag was more than US$2 billion and costs for defending infrastructure along other coastal cities are similarly eye-watering. “You can build defences higher, but there comes a point where you have to ask whether costs justify the outcomes,” says Williams. “When you get a one in 100-year flood, people build back. But what if that event happens again the next year, and then the year after that?”

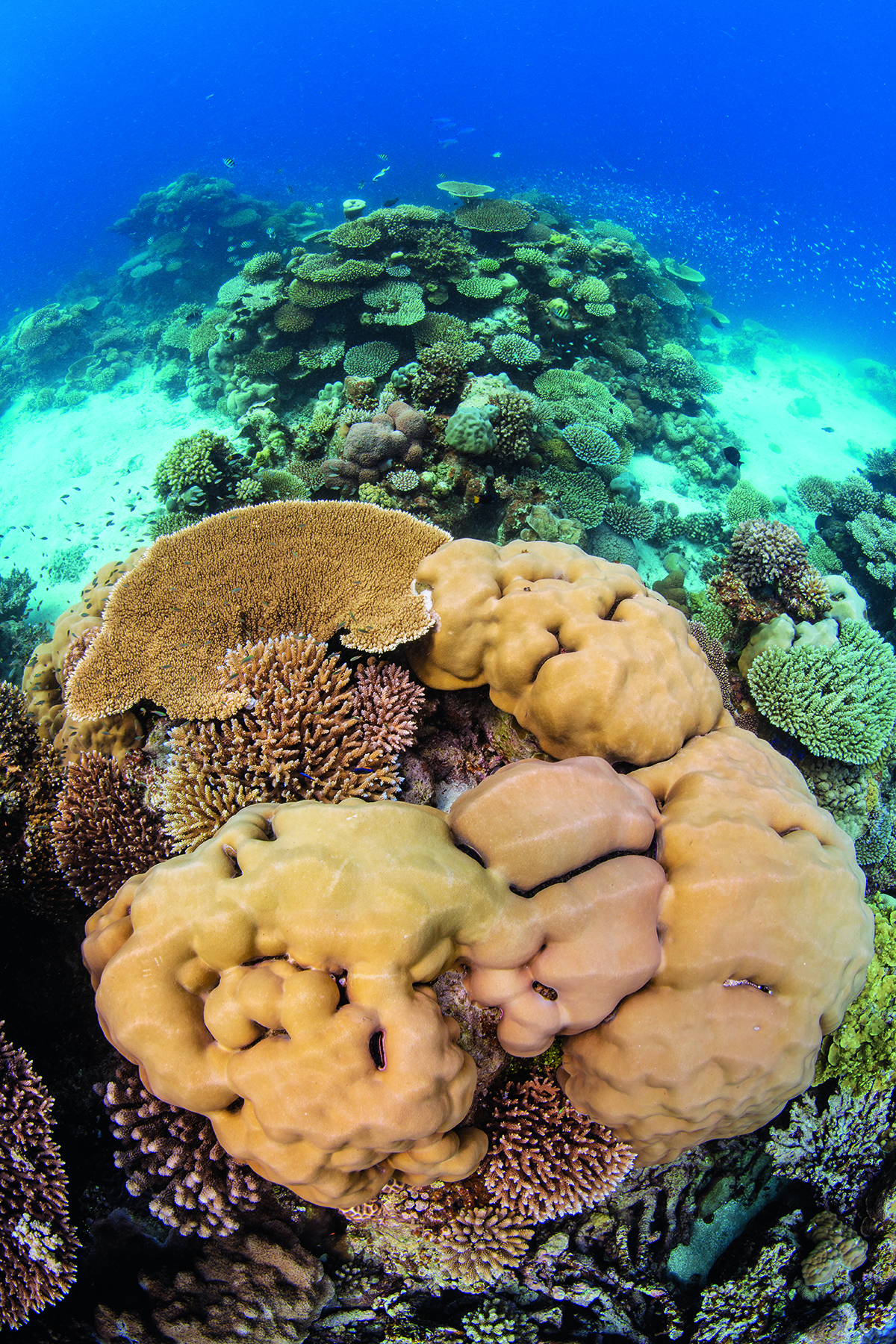

This is where nature-based solutions come in. While many cities in advanced economies – those, remember, primarily responsible for climate change – have the means to protect themselves through technological solutions, the picture is different in the Global South, says Rode, where emphasis is more on adaptation. Barrier islands, vegetated dunes, coastal wetlands, mangrove forests and reefs are examples of natural barriers to protect shorelines.

They provide several advantages in addition to flood protection, including carbon sequestration, biodiversity restoration, fish nurseries, cultural heritage, recreational activities, tourism and spiritual benefits. Crucially for the Global South, they can be quickly adapted to the real pace of sea-level rise. Planting mangroves can lower wave heights by 71 per cent or more.

Mangroves originally lined tens of thousands of kilometres of coastlines around the world; previously mistakenly seen by humans as a type of coastal weed that could be destroyed for development, they are a good example of the upside potential of mitigation. Properly managed, mangroves store immense amounts of carbon and support a rich ecosystem of biodiversity, as well as protecting the developments on the coasts they have previously been cut from. They survive in a variety of climates and in brackish water, and planting mangroves can provide carbon credits.

Meanwhile, studies in the UK have shown how fringes of saltmarsh 40 metres wide can reduce wave height by nearly 20 per cent; at 80 metres, waves reduce to near zero. Nature-based solutions also give quick returns: estimates for annual flood-damage reduction from coral reefs exceed US$400 million for Cuba, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico and the Philippines alone.

Fresh, innovative approaches to protect urban areas include creating holistic “sponge cities”, which absorb heavier rainfall. After a cloudburst in 2011 inundated Copenhagen’s main trauma hospital and caused US$1.04 billion of damage, the Danish government redesigned infrastructure to make roads and pavements more permeable, while using nature-based solutions to plant grass and lay soil to better absorb rain.

Information-gathering to facilitate decision-making is key. Many countries use Lidar, a remote sensing method that pulsates laser light across coastal areas to measure elevation on the Earth’s surface. Australia’s web portal CoastAdapt provides mapping software, coastline morphological information, guidance for decision-making in coastal climate adaptation, and local and international case studies. France, meanwhile, is one country using a combination of a tech-based approach to monitor and evaluate its progress to date, and using that to recommend the elaboration of nature-based solutions and proposals to spatially reshape coastal areas.

The artificial peninsula whose sand, as it erodes, protects the natural beaches near The Hague © Craig Corbett

The Netherlands, with 25 per cent of land below sea level and scarred by the North Sea flood of 1953, is widely considered the gold standard, with a creative approach combining monitoring, preparation, and grey- and nature- based engineering. “It did a lot of learning, a lot of thinking,” says Michaels. Anticipating sea-level rises of one metre by 2100, its measures have included the 2003 US$70 million reconstruction project to protect The Hague by raising a dyke 10 metres above the mean water level in Amsterdam and depositing 2.4 million cubic meters of dredged sand along Scheveningen Beach, which pushed the ocean back 50 metres from the shoreline.

Meanwhile, the necessary shift to a more sustainable economy offers the opportunity to restructure many firms and their manufacturing processes. Physical damage to facilities as a direct consequence of flood events or other weather extremes interrupt production and make it hard for employees to show up at work. It makes sense that forward-thinking companies across the globe are preparing for climate change by investing in resilient structures that can resist storms, severe winds and flooding.

Coastal cities may have to be radically redesigned or risk becoming “misshapen”, as Michaels puts it. “Inland cities have development that radiates from a central business district in all directions,” he says. “For coastal cities this is not an option. Rising sea levels will further distort the shape of coastal cities, leading to them becoming misshapen and significantly lengthening the costs of commuting to work.”

Michaels is struck by how stubborn communities can be. “Between 1990 and 2010 we saw development increase by 26 per cent in city blocks prone to sea-level rises on the US east and Gulf coasts,” he says. “That was alarming. We assumed people would avoid building there – the exact opposite happened.”

Read more: YKK America’s CEO Jim Reed on creating sustainable products for less

Thumbing a nose at climate science only partly explains this, suggests Michaels. “If you assume people have good foresight but still do it, then they’re building in riskier locations because that’s where the jobs are. It’s a trade-off.” Is there a link to the politicisation of climate change? “People who are least aware of climate change can be the most willing to take on risk,” he says, citing politically sceptical Florida. “Miami is at ground zero. The coast is long, low-lying and very vulnerable. Yet there doesn’t seem to be a wide acceptance of what is happening and many locals regard most events as ‘nuisance’ flooding.”

What will trigger meaningful long- term, joined-up action? “Disasters recede into the background quite quickly,” says Michaels. “Maybe that changes if we get a Hurricane Sandy or a Katrina every year.” Williams is more optimistic. “I see people putting the effort in. It’s important not to say things are impossible, otherwise people ask why they or their government should bother taking any steps.” Rode reckons a more fundamental societal shift is required. “Free-riding, the good life as we know it, goes far beyond levels of consumerism that are healthy for the planet. Maybe we need to rediscover the mundane, then decide whether what’s really meaningful in life is that your local river is clean enough to swim in.”

Find out more:

deutschewealth.com/dam/deutschewealth/cio-

perspectives/cio-special-assets/coastlines-in-crisis

This article first appeared in the Deutsche Bank Supplement of the Autumn/Winter 2023/2024 issue of LUX magazine

Can we put a price tag on nature? Valuing the carbon services of plants and animals is essential to bridging the gap between finance and conservation, says Professor Connel Fullenkamp, the leading academic working at the intersection of science and economics. Here, Fullenkamp speaks to LUX about the importance of engaging capital markets in biodiversity financing, and why necessity is the mother of invention

Can we put a price tag on nature? Valuing the carbon services of plants and animals is essential to bridging the gap between finance and conservation, says Professor Connel Fullenkamp, the leading academic working at the intersection of science and economics. Here, Fullenkamp speaks to LUX about the importance of engaging capital markets in biodiversity financing, and why necessity is the mother of invention

1. What inspired you to become a photographer, particularly in the polar regions?

1. What inspired you to become a photographer, particularly in the polar regions?