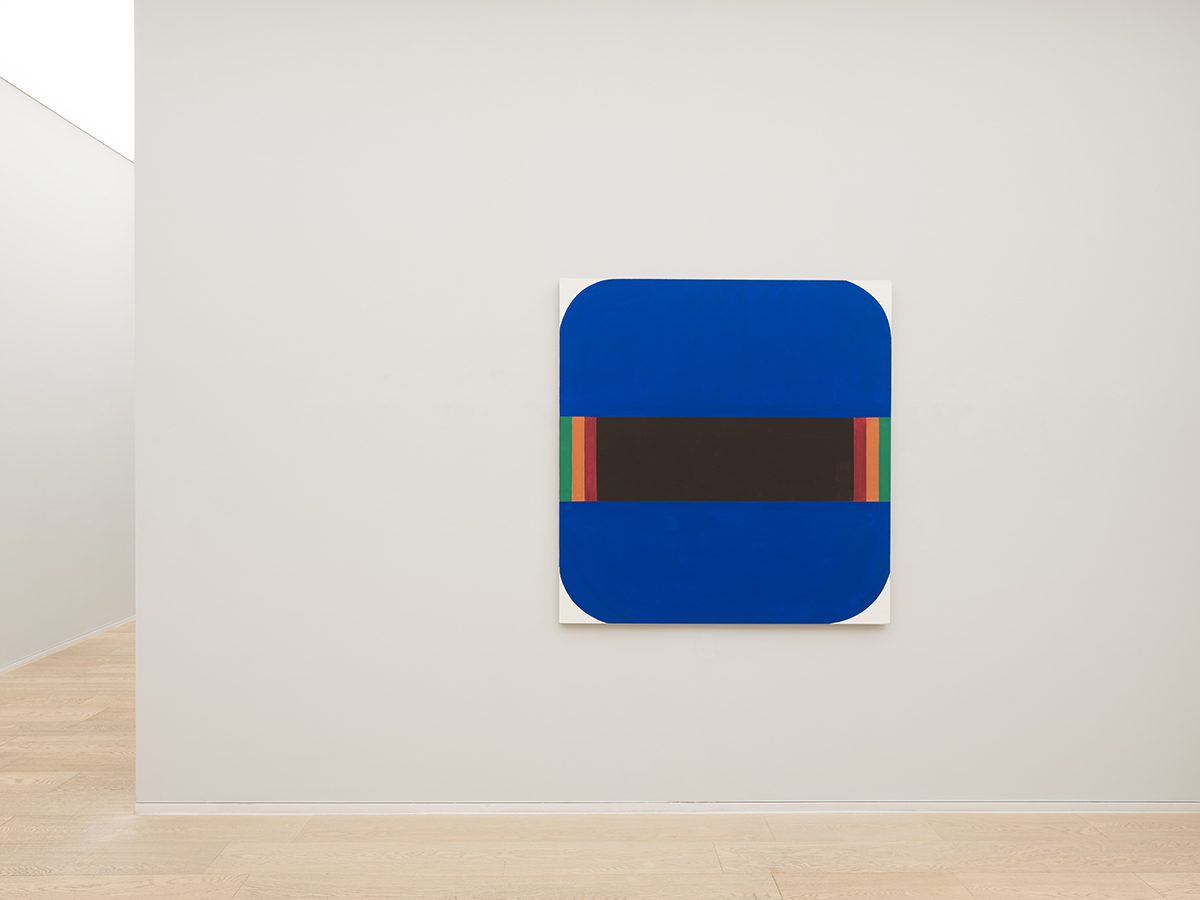

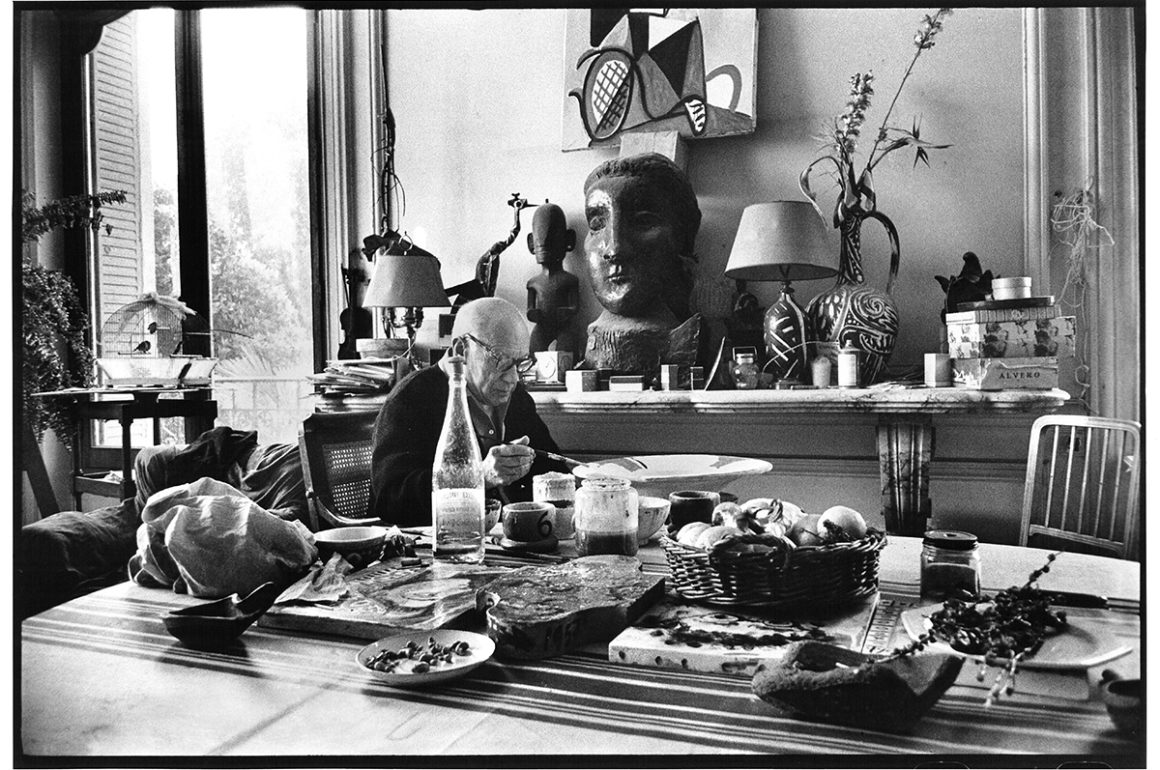

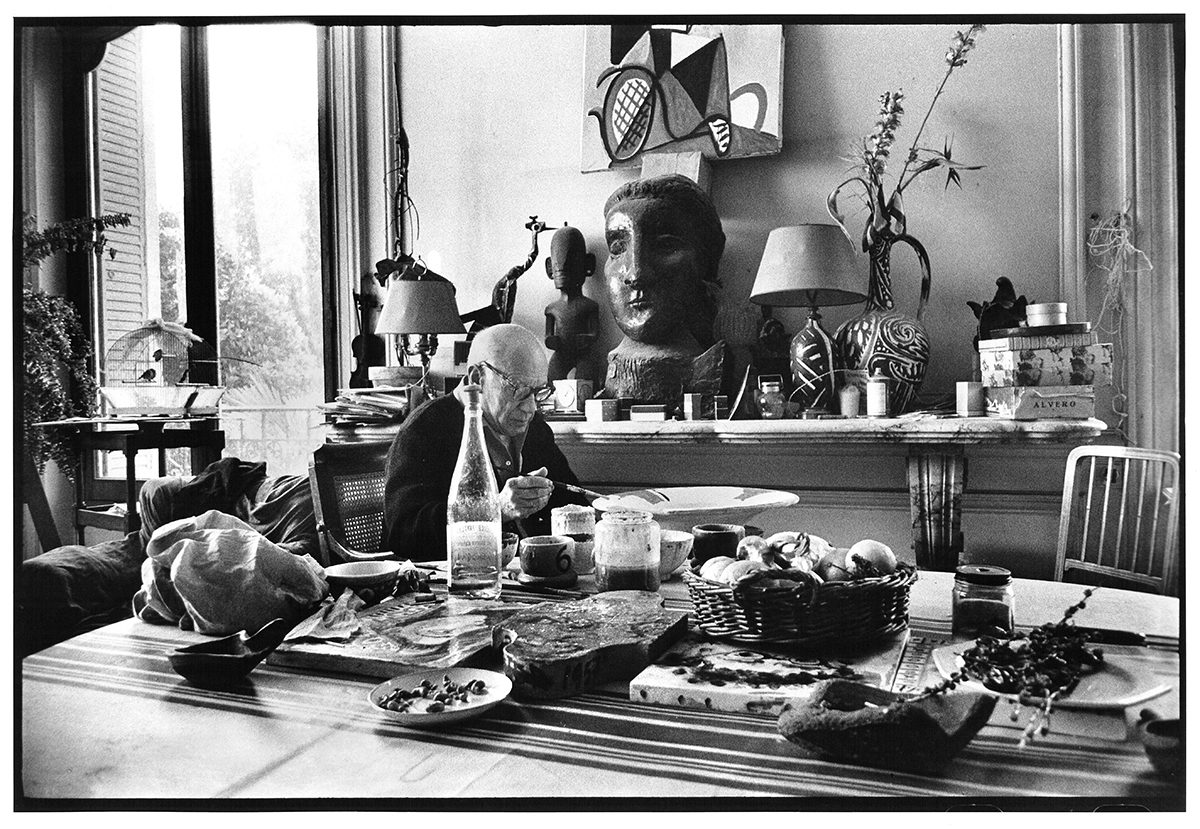

Georg Karl Pfahler in his studio, 1965

Our contributing editor and columnist Sophie Neuendorf caught up with renowned Mayfair gallerist Simon Lee to discuss the Asian art market, NFTs and the enduring influence of Georg Karl Pfahler

Sophie Neuendorf

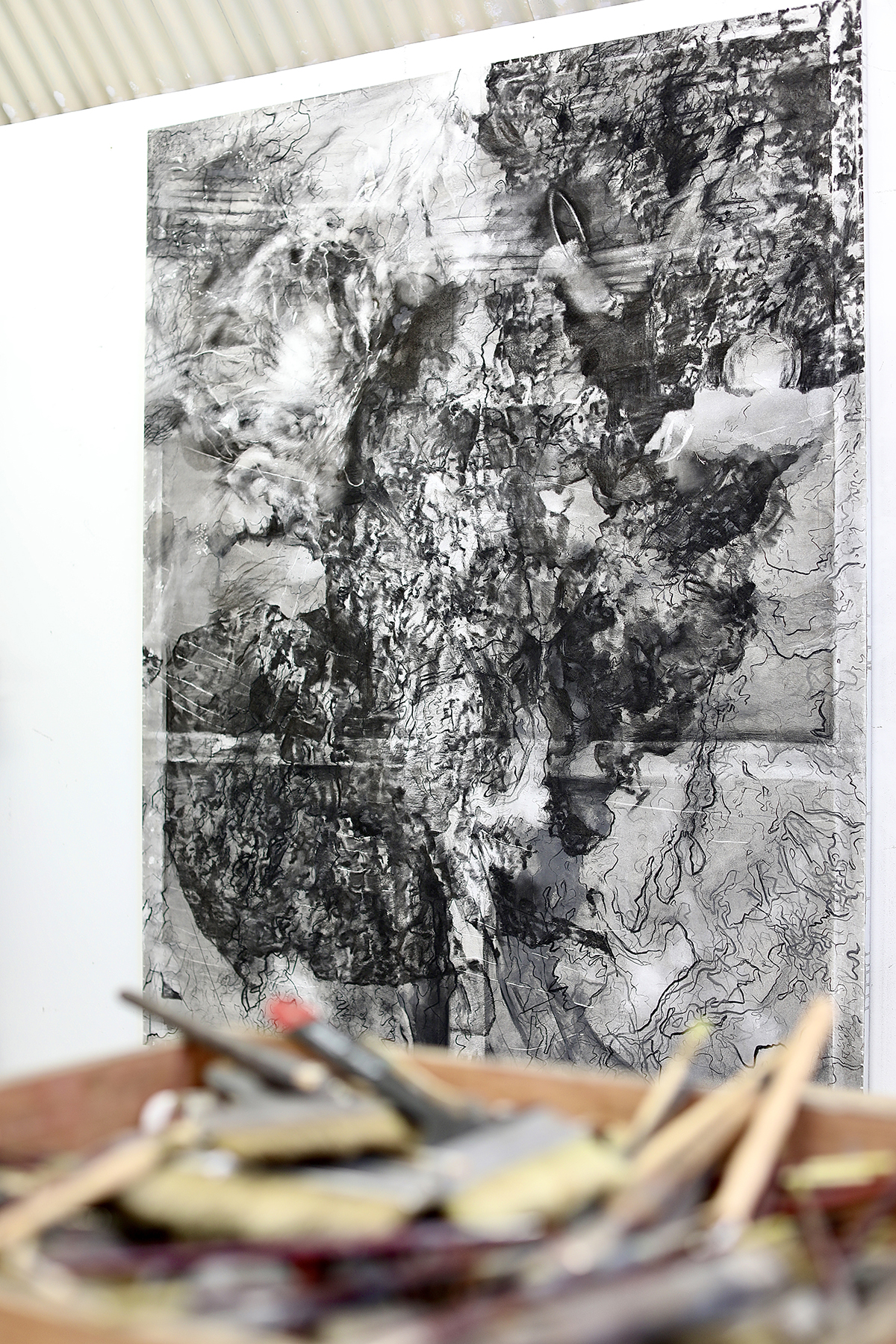

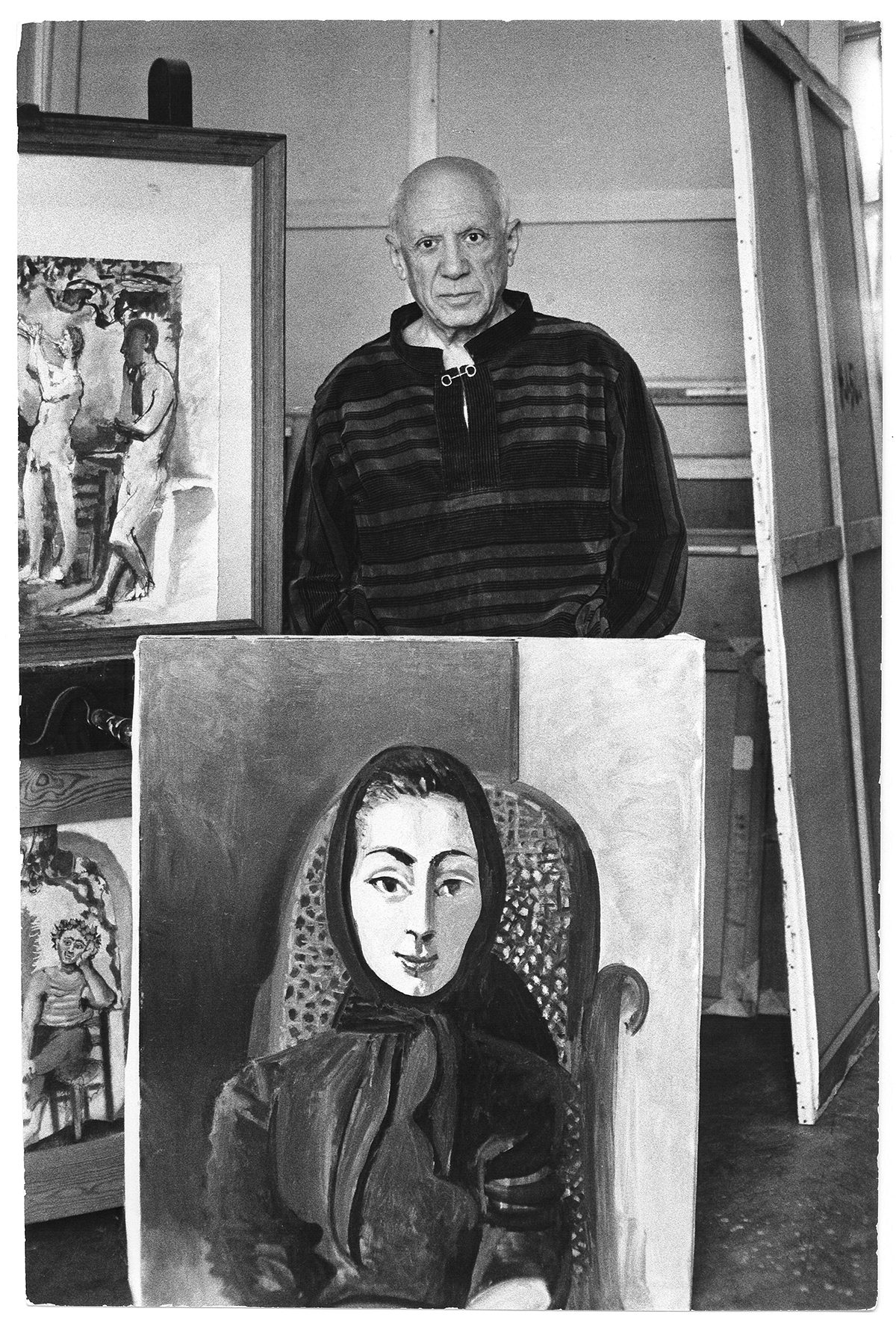

Simon Lee has always been at the forefront of artistic movements and changes in taste, showing emerging and established artists that represent the zeitgeist and rapidly gain popularity. Now, he’s presenting the first ever exhibition of German hard-edge painter GK Pfahler (1946-2002) in Asia.

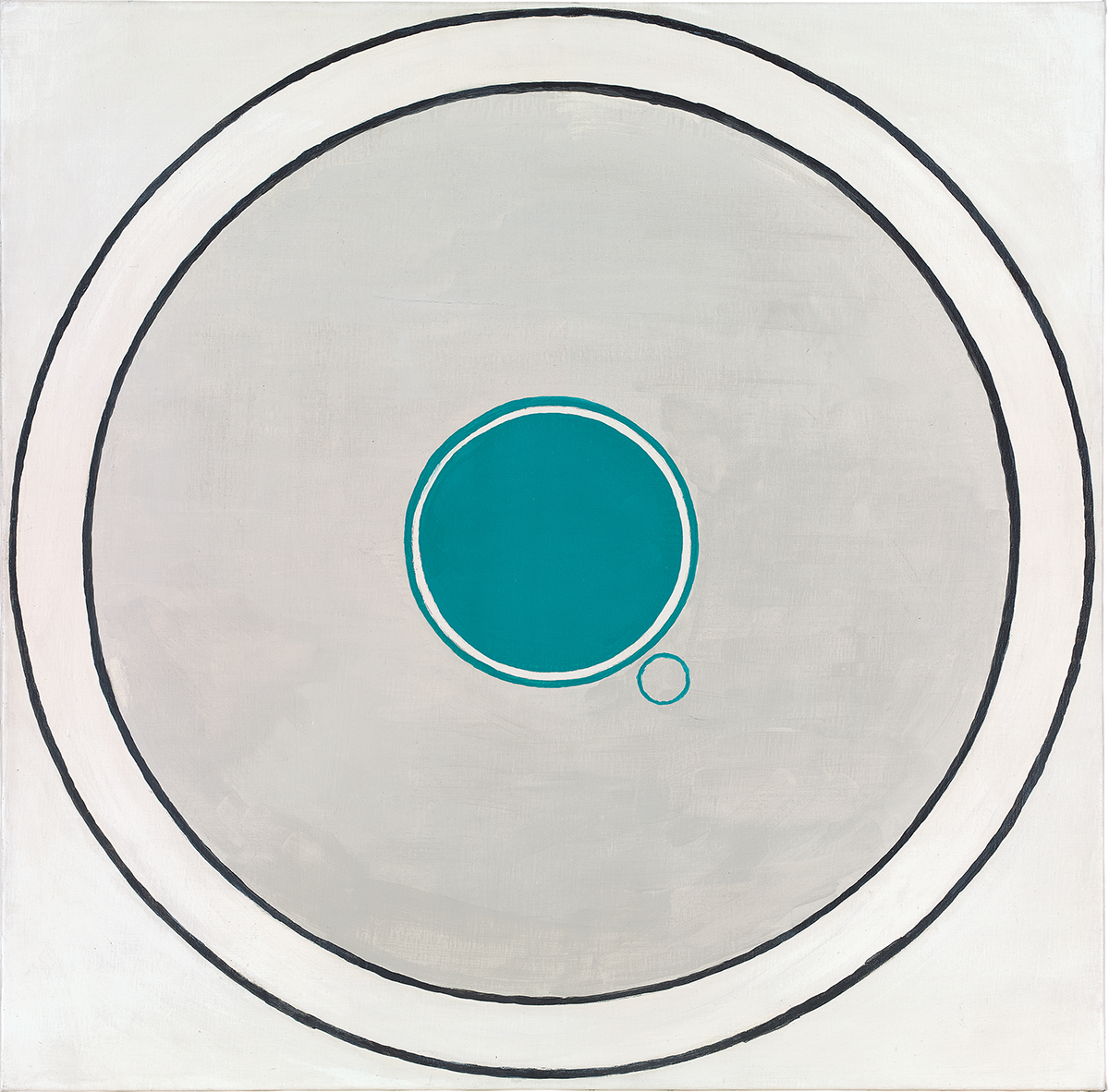

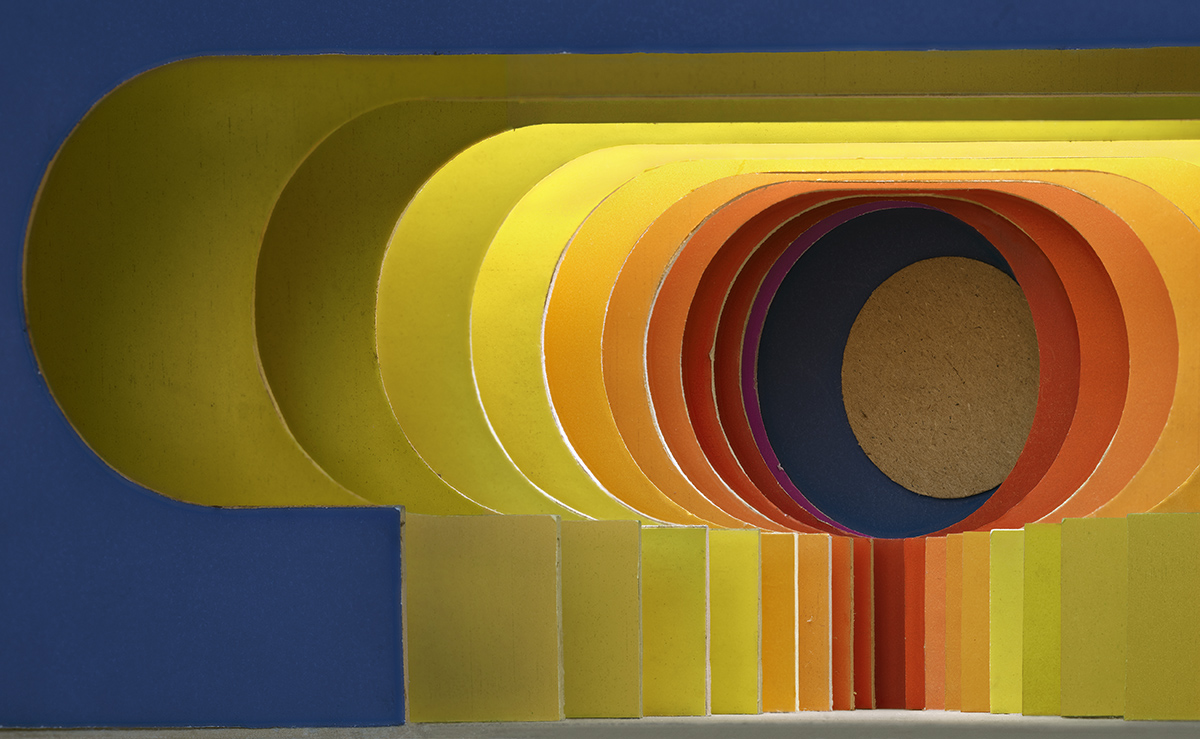

Pfahler’s dogged pursuit of the hard-edge style make him one of the most unique German artists of the last half century. Throughout his career, his work remained steadfastly focused on the interplay of space, shape and colour. At the same time, his paintings contain traces of pop and minimal art, unifying two of the most prevalent styles of the 1960s.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

During his lifetime, Pfahler exhibited alongside artists such as Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, and Kenneth Noland in shows such as “Signale” at the Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland and went on to represent Germany alongside Gunther Uecker and Heinz Mack at the Venice Biennale in 1970. In the decades that followed, Pfahler continued to experiment with the constraints and boundaries of painting and today, his work remains more relevant and perhaps, even more cutting-edge than much of the contemporary art being shown and hyped.

Sophie Neuendorf: 2021 has been quite a tumultuous year for most galleries. How do you feel about the changes we have experienced within the art business?

Simon Lee: The pandemic has given rise to some fundamental shifts in the way art is mediated and bought. Online sales have greatly expanded the reach of the art market and we have seen a corresponding shift in taste and commercial success.

Sophie Neuendorf: Recent reports suggest that Asia is a force to be reckoned with in terms of creativity and sales, even post-pandemic. What insights can you reveal from your years of experience in Hong Kong?

Simon Lee: Asia has seen tremendous developments across many industries over recent years and I think that the overall growth in the economy, alongside technological advancements and adaptation has contributed to the flourishing creativity seen in the art world. There has been a huge increase in young collectors and the interest in art of this young and active group of people has risen exponentially as their taste becomes increasingly sophisticated and international. The pandemic inevitably provided people with more time on the internet and social media platforms to discover new artists and experience art in a different way.

Sophie Neuendorf: You’re opening a show of German artist Georg Karl Pfahler in Hong Kong this month. What motivated you to choose a hard-edge painter for Asian collectors?

Simon Lee: It’s very exciting to be presenting Pfahler’s work for the first time in Asia and to introduce him as part of the gallery programme with his inaugural exhibition in the Hong Kong space. The language of abstraction and colour in Pfahler’s work is of historical importance but it also feels very contemporary and is something that Asian collectors engage with well. Pfahler is a very well-known artist in Germany but hasn’t had much exposure in other parts of the world so it’s a privilege to give the opportunity for an Asian audience to discover his work.

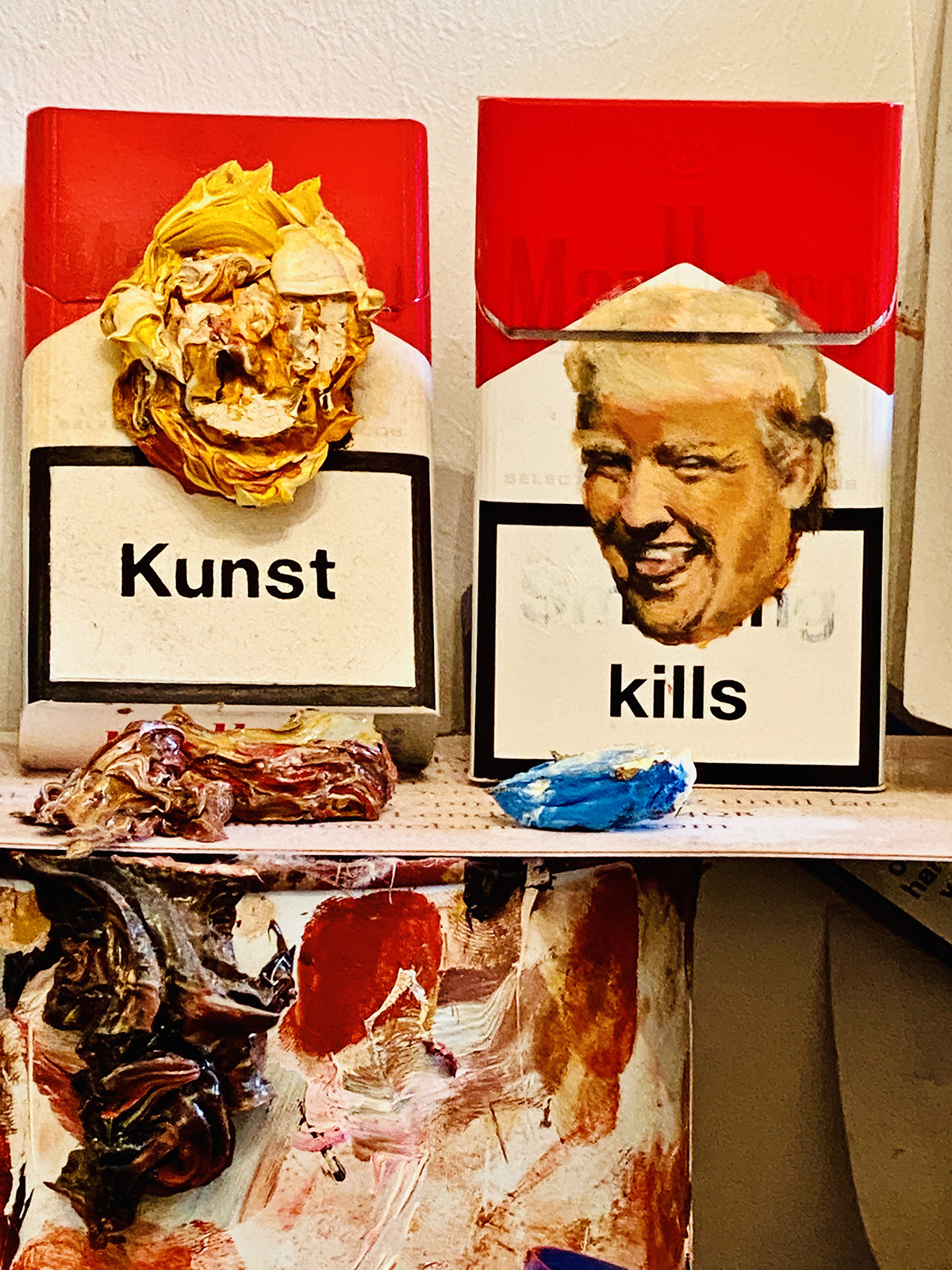

Read more: Shiny Surfaces, Lawsuits & Pink Inflatable Rabbits – In Conversation with Jeff Koons

Sophie Neuendorf: Pfahler was, and continues to be, an inspiration for many artists as a pioneering hard-edge painter. When was the first time you experienced one of his works and how does it feel to represent the estate?

Simon Lee: Pfahler’s work has had a lingering presence in my career dating back to the 80s and 90s, when I spent a lot of time in Germany and first discovered his work. Over the years I saw his works pass through auction houses and when the opportunity came along to view his work again, I found them very compelling and relative to the gallery programme. It’s a pleasure to be working with the estate and I’ve been particularly impressed with how organised they are. There are fascinating archival materials and historical documents, which we are excited to share with a wider audience across our platforms and publications.

Sophie Neuendorf: Are you planning a London show of Pfahler as well?

Simon Lee: Yes, we look forward to presenting a more comprehensive survey show next Spring in the London space.

Sophie Neuendorf: If you could juxtapose Pfahler with any two other artists who would you choose?

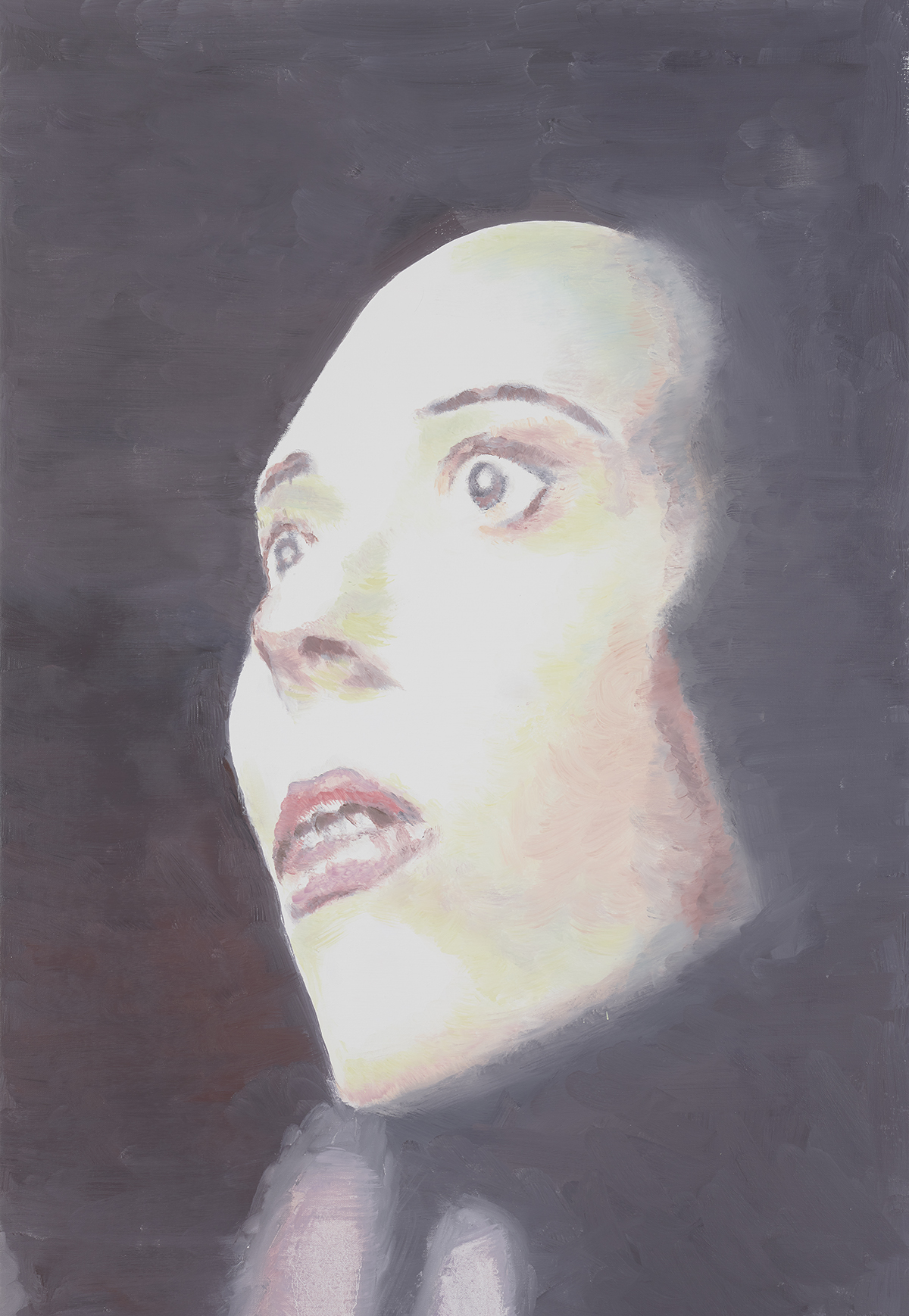

Simon Lee: Looking at our programme, I would say Angela Bulloch and Sarah Crowner. Pfahler, Bulloch, and Crowner’s practices all present similar investigations into colour, shape and space. There are spatial and architectural elements in all their works. Crowner embraces the idea of painting as object and her works embody the experience of architecture and space both within themselves and their display, especially her tile works that echo Pfahler’s experiments with environments and art, and which embrace the spectator. Bulloch’s work also engages with architecture, colour, and mathematics, her stylised geometry recourse some aspects of Pfahler’s hard-edge sensibility.

Sophie Neuendorf: Richter, Uecker, Mack, Pfahler… Germany is known for producing a plethora of important and popular artists. How do you feel the German market will develop over the near future?

Simon Lee: The German market is constantly evolving. It’s a large nation with many talented artists and many young artists that are gaining a lot of attention. There’s a great tradition of German modern and contemporary art which has transcended national boundaries so I’m sure the market will reflect this. The art market has become truly global, reinforced by digital communication but there are certainly many talented German artists playing a role at the forefront of this market.

Read more: Maryam Eisler’s Spectacular New Photography Exhibition Opens At Linley In London

Sophie Neuendorf: NFTs are all the rage right now. Will you enter the market?

Simon Lee: We’re certainly exploring the opportunities that exist in this sector and market. There seems to be a growing recognition of the fact that NFTs will be a feature of an emerging mainstream market.

Sophie Neuendorf: How do you choose the artists you represent? Is it a gut feeling or more analytical?

Simon Lee: It’s neither one nor the other but a combination of many factors that play a role in selecting our artists. Certain people carry more weight than others with their recommendations but, it’s most important to consider the overall gallery programme and the connection to our other artists. I look at both our established artists and emerging artists to see how their practices and works link together. It’s interesting to me to observe this in artists that are at different points of their career.

Sophie Neuendorf: If you could have dinner with any 3 artists, living or dead, who would you choose and why?

Simon Lee: I’ve dined with many great living artists and sadly some dead ones as well, but of those who I’ve never met and are no longer with us, I would say Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Titian as I love Italian food. Other scenarios would have to include Rothko, de Kooning, and Pollock or Cézanne, Monet, and Kandinsky.

“Georg Karl Pfahler” runs until 8 January 2022 at Simon Lee Hong Kong.

Sophie Neuendorf is Vice President at artnet. Find out more: artnet.com

Recent Comments