Olaffur Eliasson photographed for LUX in his Berlin studio by Simon de Pury

Olafur Eliasson is an artist of global renown, a former breakdancing champion, an academic and a passionate champion of the planet. Simon de Pury, auctioneer extraordinaire and long-time LUX collaborator, creates art collections for the world’s super-wealthy and runs celebrity charity auctions with a biting silver tongue. De Pury travelled to Eliasson’s Berlin studio and home, where the two discussed light, communication, birthdays, art and the human rights of the planet’s plants and creatures

Simon de Pury: First, a question I often asked when I was interviewing someone for a job: if you could be an animal, what would you be?

Olafur Eliasson: I would be a jellyfish, I think. They move so graciously and they’re very slow. I like that a lot.

The Serpentine Pavilion lamps, 2007, by Olafur Eliasson. Photograph by Simon de Pury

SDP: I heard that you have a winter birthday.

OE: Yes, the 15 February.

SDP: So that makes you Aquarius. Do you follow astrology?

OE: No, I don’t. It’s remarkable that everything always fits. It’s a little bit like fortune cookies. It’s always nice… it’s like: you’re going to meet a friend next week. That cannot be wrong. But I think the question is whether we have room in our life for matters that don’t really fit into Western science.

Read more: Interview with Claire Ferrini of Astrea London

I think Western science falls short of providing a safe future. You could refer to indigenous knowledge, for example, or knowledge about trees, the forest, the cyclical nature of weather and seasons, and how to treat nature and so on. It is remarkable to observe that these knowledges are considered absolutely non- functional or non-important by the rationalised or pragmatised minds of Western society.

And it turns out that there is a lot of insight into happiness, success and health that indigenous knowledge addresses. The trees are not as simple as we humans thought they were. And this gives us a great opportunity. When we see a tree, instead of saying, “Oh, there is a tree, what can I use that for? Can I make money with it?”, we can become crucially aware that if we indeed keep exploiting or extracting nature, we are going to ruin our own livelihood, the wellbeing of the planet.

The first set of designs for the LUX logo by Olafur Eliasson

SDP: I recently saw a Belgian businessman who is based in Brazil. He was discussing a project with an Amazonian gentleman who told him: listen, I first need to consult the trees. Once the trees gave a positive feedback, they were able to kick off their project.

One of the most fascinating experiences I’ve ever had is when I attended the annual Summer Nights gala you curated for the Fondation Beyeler. You staged an incredible environment just for that one night and your sister provided amazing food.

When we entered the room where the dinner was to take place, everything was in black and white. We suddenly experienced the world as if we were colourblind. The weirdest thing was eating food when it’s only black and white. You got up and started to give a speech, you pressed a trigger and colour reappeared as by a miracle! I have no clue how you pulled that off.

The playful evolution of Olafur Eliasson’s LUX logo designs

OE: Yes. White light, like sunlight, is the spectrum of all the colours of the rainbow. If the white light missed a colour in it, then it would miss in the rainbow. We know Newton’s lens with the prism [where white light enters the prism and emerges on another side separated into the colours of the rainbow].

White light is the visible area of the electromagnetic spectrum. Each colour has a special wavelength, measured in, I think you call it a nanometre. This is how light works, right? There is a yellow light in the yellow spectrum that is 100 per cent monochromatic. In our eyes, we have what are called receptors for light: we have blue, red and green. We actually don’t have yellow because the mix of red and green produces yellow.

Read more: 180 years of history with Penfolds

If you have this monochromatic yellow light and there’s no other white light, you are, in fact, only seeing a black and white image. Humans are capable of seeing more grey tones than colour tones. That’s why a black-and-white photo by Ansel Adams can sometimes look more real than the same photo in colour.

So you realise that our eyes really influence our brain to interpret visual information – say the food on your plate. The vegetable, you thought, is green because it appears to be in the shape of an asparagus. But actually it could be an orange carrot. This means that I already have a predetermined opinion about what I’m looking at and that influences what I’m looking at. Perhaps this is why we have a hard time changing our mind. It is what the brain tells us we are seeing. That’s interesting, because it suddenly throws up that reality is relative. For me, it shows how you are the author of your own responsibility with regards to what and how and why you see. You can choose to change your view.

The final Olafur Eliasson design for the LUX logo, as seen on the cover of our Winter 2025 issue

SDP: At the Summer Nights gala, we all had under our seat a Little Sun. Can tell us about it?

OE: Occasionally, I have organised events using a little handheld solar lantern called Little Sun. It’s a handheld little power station, which has a solar panel, strong and qualitative. The Little Sun project was to advocate and build awareness around sustainable energy. So it also has that little educational offering to have confidence in solar panels. Because 15 years ago, when we were testing the very first slides, some people would say, well, I don’t believe in solar panels. Now everyone knows what a solar panel is. We have delivered one million off-grid lanterns in sub-Saharan Africa. A large amount of our lamps – I believe one-third – are distributed at no cost in places where there is no economical infrastructure, such as refugee camps. My co-founder of Little Sun, Frederik Ottesen, has now for many years lived in Zambia to build this.

SDP: When Sam Keller, Director of Fondation Beyeler, introduced you that night, he said, “Olafur Eliasson is a 21st-century Leonardo da Vinci.” In your practice as an artist, an activist, an environmentalist – in your multiple activities, who do you measure yourself with?

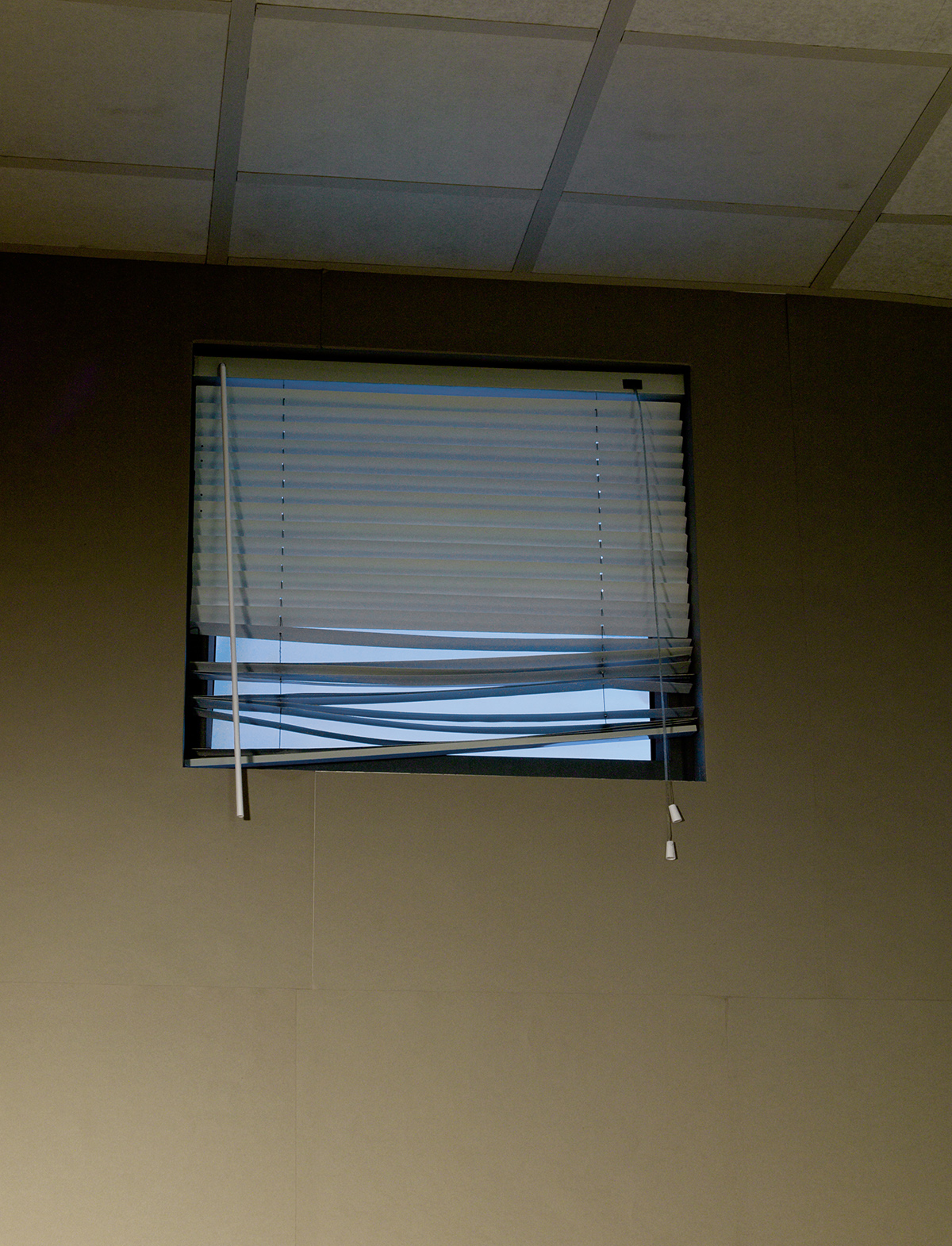

The complete sphere lamp, 2015, by Olafur Eliasson. An open woven basket afixed to a circular mirror that creates a ‘complete sphere’

OE: I am really grateful for what I have been doing. My studio in Berlin has a 30-year anniversary this year and I’ve been very focused on how to give back to younger artists, their conditions and teaching at art school. I have my amazing studio team; I have the same two gallerists that I started with: Tim Neuger & Burkhard Riemschneider here in Berlin, and Tanya Bonakdar in New York. I admire people like I admire the jellyfish for its easygoing way of swimming. I never was very focused on competition or the idea of the heroic act.

Follow LUX on Instagram: @luxthemagazine

I am momentarily very inspired by the structural language specialist, the late Marshall Rosenberg. I’ve thrown myself into quite an intense study of this founder of nonviolent communication. It is about speaking and acting without inflicting judgment or threatening people you have disagreements with. I think art can address, not just the feelings that people bring to the room, but also their needs. There is much less likely to be a conflict or a polarisation, if we can state our needs fundamentally.

Needs can be very personal: we want to have a life, we want to be acknowledged, we want to be healthy, we want an education, and so on. I have a need for silence, because I get anxious if I don’t have silence.

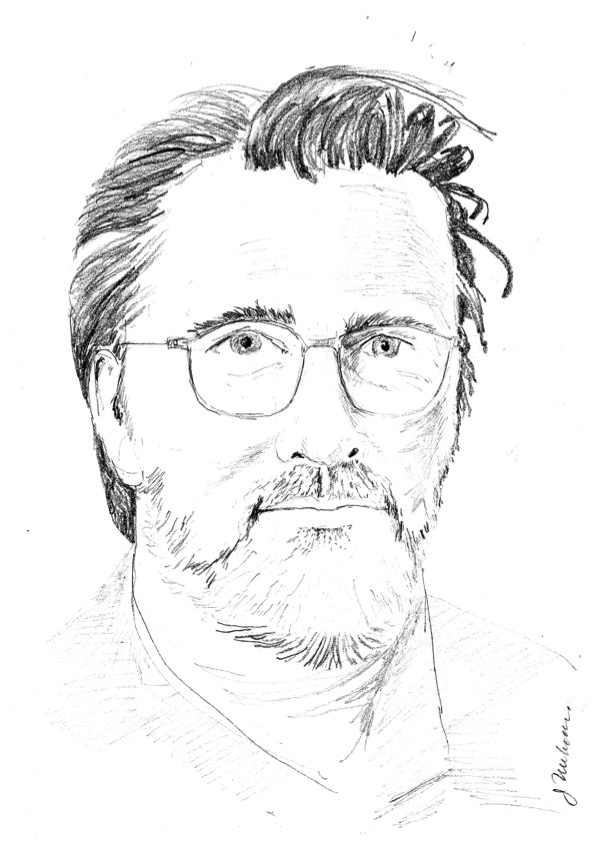

A portrait of Olafur Eliasson by Jonathan Newhouse, for LUX magazine

SDP: One of the reasons I’ve always loved art is that art is one thing that can bring us closer together. To hear you speak now about nonviolent communication is riveting. I didn’t realise that this was also part of your focus.

OE: It’s a recent development. I keep finding out that the world is quite amazing. I remain humble and grateful for the many opportunities and in particular for the incredible career I’ve had. And there are many, many collectors and artists and friends and gallerists and museums who have believed in me.

Read more: Why preventative healthcare is essential

SDP: It’s extraordinary to realise that your career already spans 30 years. Your list of achievements is phenomenal. What are your dreams going forward?

OE: Klee did this Angelus Novus, of the angel that faces the past and the wisdom of the past, but, in fact, flies backwards into the future. That was the kind of conservative idea of what is a good life. You learn from the successes of the past. The late philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour said that, considering the fact that modernity created the climate crisis, we actually can maybe conclude the past wasn’t quite as successful as we thought. The ground is trembling, it is collapsing right underneath our feet. I hope to have the courage to keep reinventing myself. And my biggest wish is that people still want to, and consider that relevant.

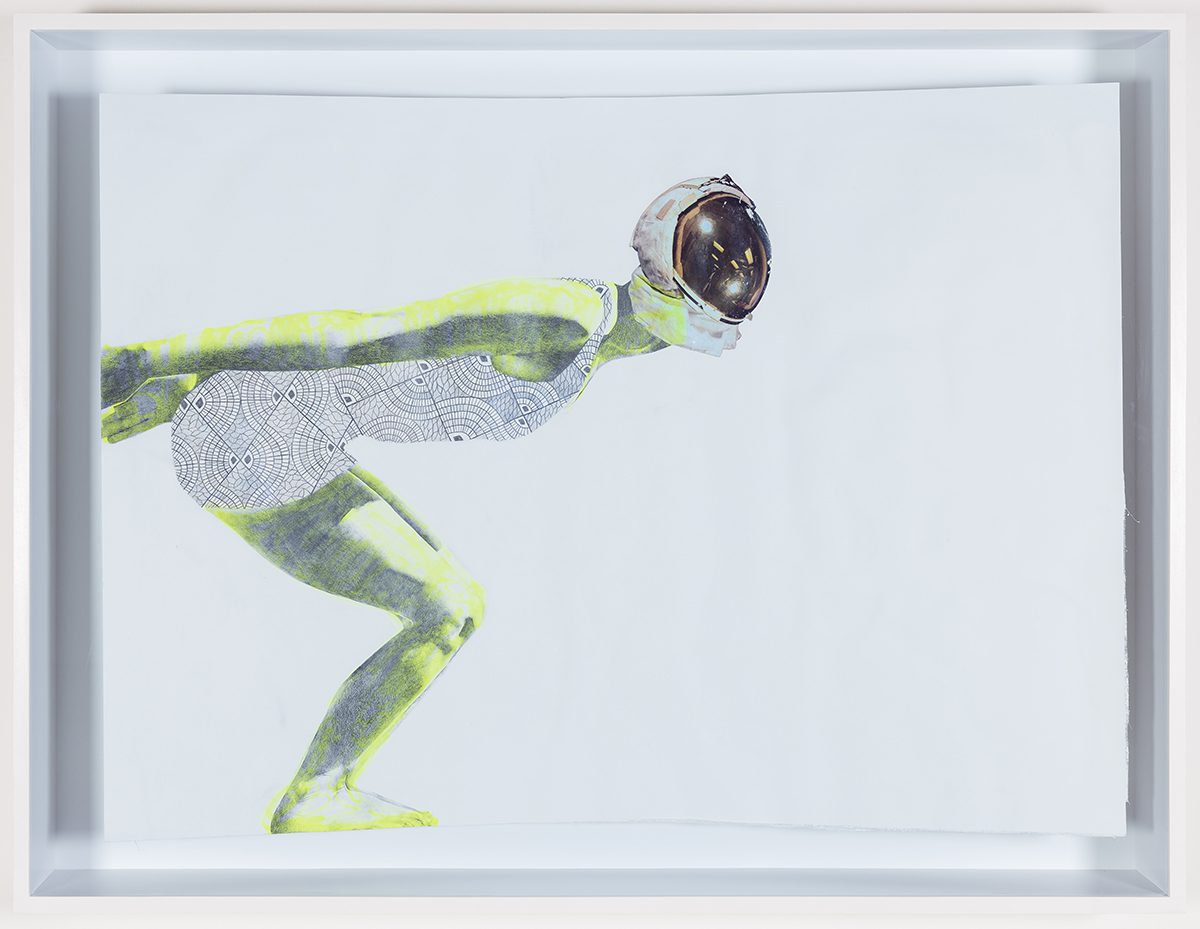

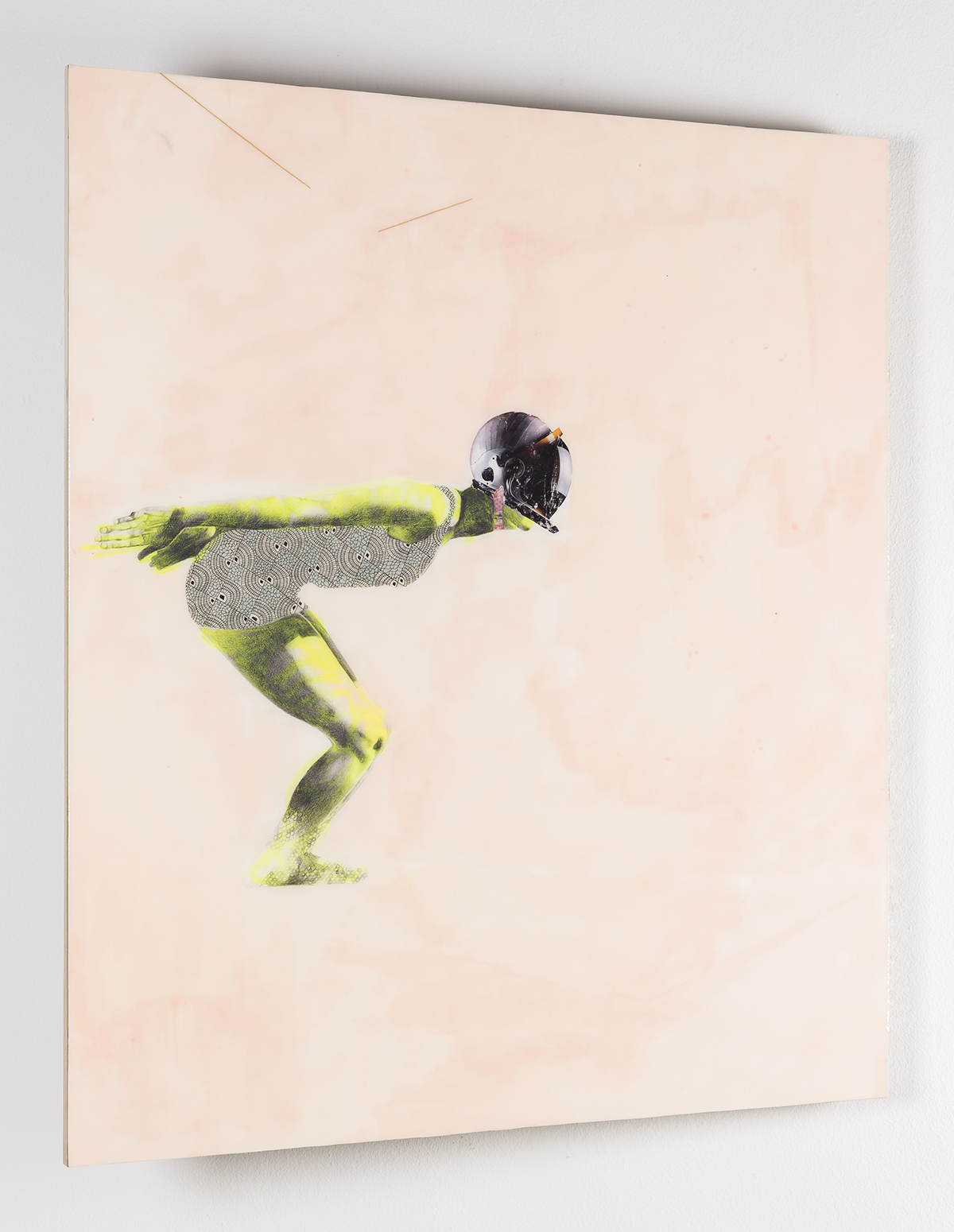

‘Shadows travelling on the sea of the day’, 2022, by Olafur Eliasson, installation view, Northern Heritage sites, Doha, from a group exhibition for Qatar Museums’ Qatar Creates, 2022

I just looked at a cartoon where a small dragon sits on the back of the panda, and the dragon asks the panda: what do you like the most, the path, the journey, or the destination? The process or the goal? My generation grew up with these questions. We said it was about the process and not the destination. The panda says, it’s the company. It illustrates the fact that we are, more often than we think, stuck in our own paradigm, and that prevents us from seeing things anew. That’s why I also named my recent show in Tokyo “Sometimes the river is the bridge”.

Hope alone is not going to change much. I believe you need to take action yourself, to get out and do it; to not only look at the horizon, but down and around, and learn from those you disagree with, find mutual company and make a movement. Then you can create change.

SDP: I always look at artists as mediums, as I feel that artists see things we don’t see yet. Artists, on the whole, are directed to the future. I feel all your activities are directed towards the future. It’s so interesting with what you said about hope. One always says hope is what dies last.

Eliasson with his 2007 ‘The Serpentine Pavilion lamps’, 2024. Photograph by Simon de Pury

OE: I think that in many ways it is also about love, to admit we all have a need for love. Maybe we need a care economy that would cater for caring for future life on this planet. There are some companies that aspire to make nature the chair of the board. There is a lot of legislative work being done by grassroots organisations, such as the charity ClientEarth, founded by James Thornton. It represented the air of London by suing the UK government for having too many pollutants. It’s a famous case. There are many countries where rights of personhood are becoming part of the legislation. Non-humans, such as mountains or rivers, have rights of personhood to protect against human intervention. I like this idea that we humans are not so exceptional any more. For one project called “Future Assembly”, I worked with others to propose that the Human Rights Charter is rewritten so that every part of the world should have a seat at the table: animals, the sky, the ocean – they should speak up for their rights.

Breathing earth sphere by Olafur Eliasson is a permanent public artwork on Docho island, South Korea, created specifically for the island’s volcanic topography, from 13 Nov 2024; “Olafur Eliasson: your curious journey” is at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 7 Dec 2024- 24 Mar 2025; aucklandartgallery.com

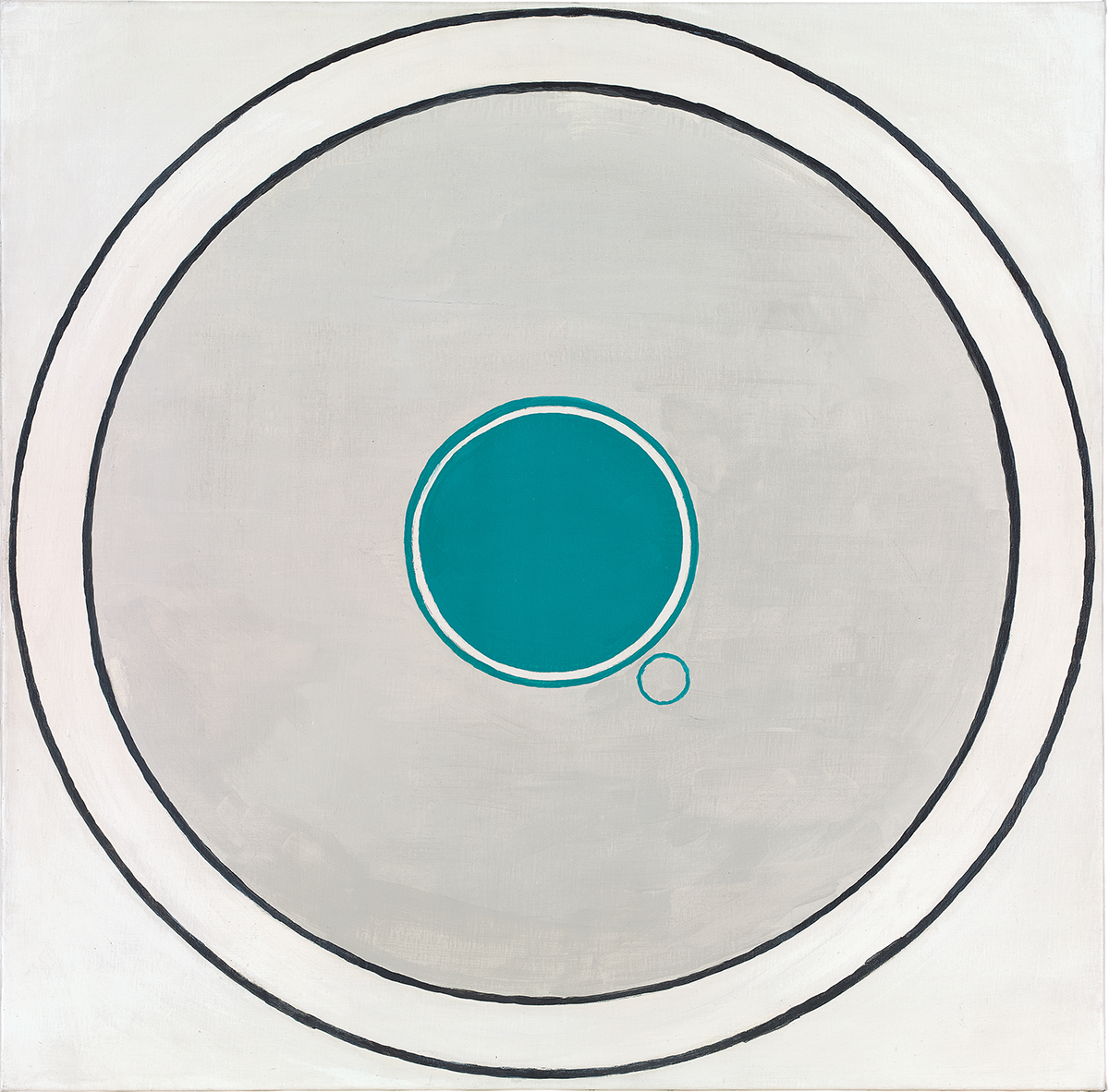

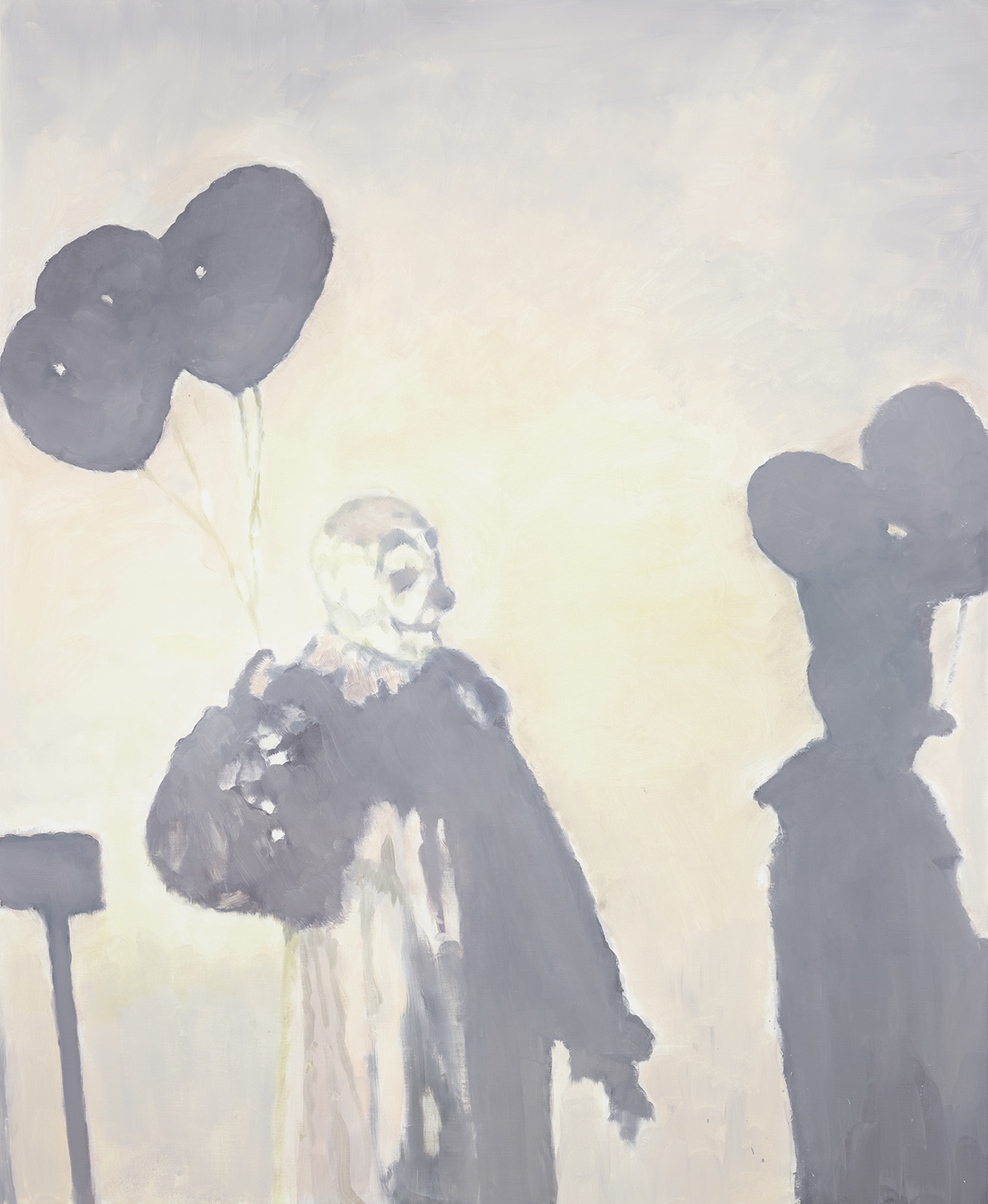

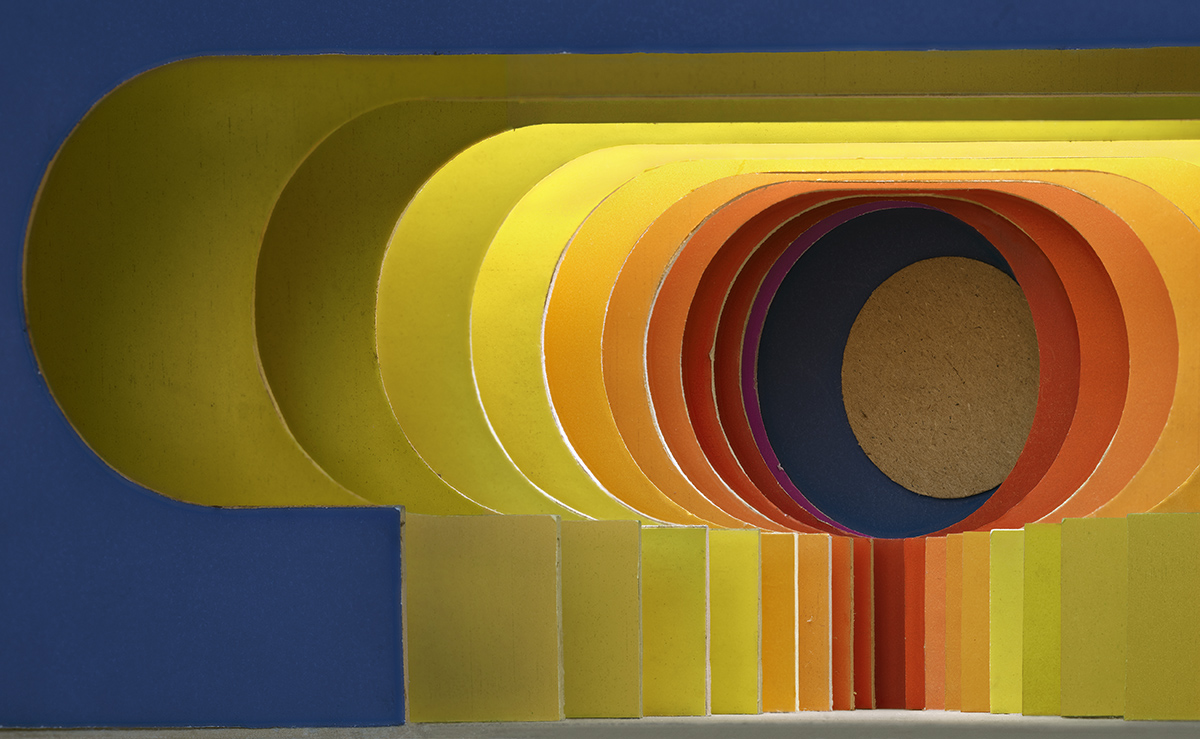

In the mid 1960s, Michael Craig Martin emerged as a key figure in early British conceptual art, later becoming the teacher of many of the YBAs such as Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas. Today, he is one of the world’s most prominent artists, known for his brightly coloured paintings and sculptures of everyday objects. Millie Walton speaks with him about colour, style and listening to his own advice

In the mid 1960s, Michael Craig Martin emerged as a key figure in early British conceptual art, later becoming the teacher of many of the YBAs such as Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas. Today, he is one of the world’s most prominent artists, known for his brightly coloured paintings and sculptures of everyday objects. Millie Walton speaks with him about colour, style and listening to his own advice

Recent Comments