Although Jeff Koons has had a profound impact on contemporary art and remains one of the world’s most influential artists, recent data supports a strong decline in his market, reflecting the tastes of a new generation of art collections and wider cultural shifts. Sophie Neuendorf reports

“I love the gallery, the arena of representation. It’s a commercial world, and morality is based generally around economics, and that’s taking place in the art gallery,” Jeff Koons

The above quote perfectly sums up the ethos and reputation of Jeff Koons. Love him or hate him, Koons has shaped contemporary art in profound ways over the course of the past few decades. One of the reasons for this is that his work is globally recognisable and relatable – you don’t need to have studied art history to understand where he’s coming from although if you have there are deeper layers to be found. In a sense, he bridges the gap between high and low culture.

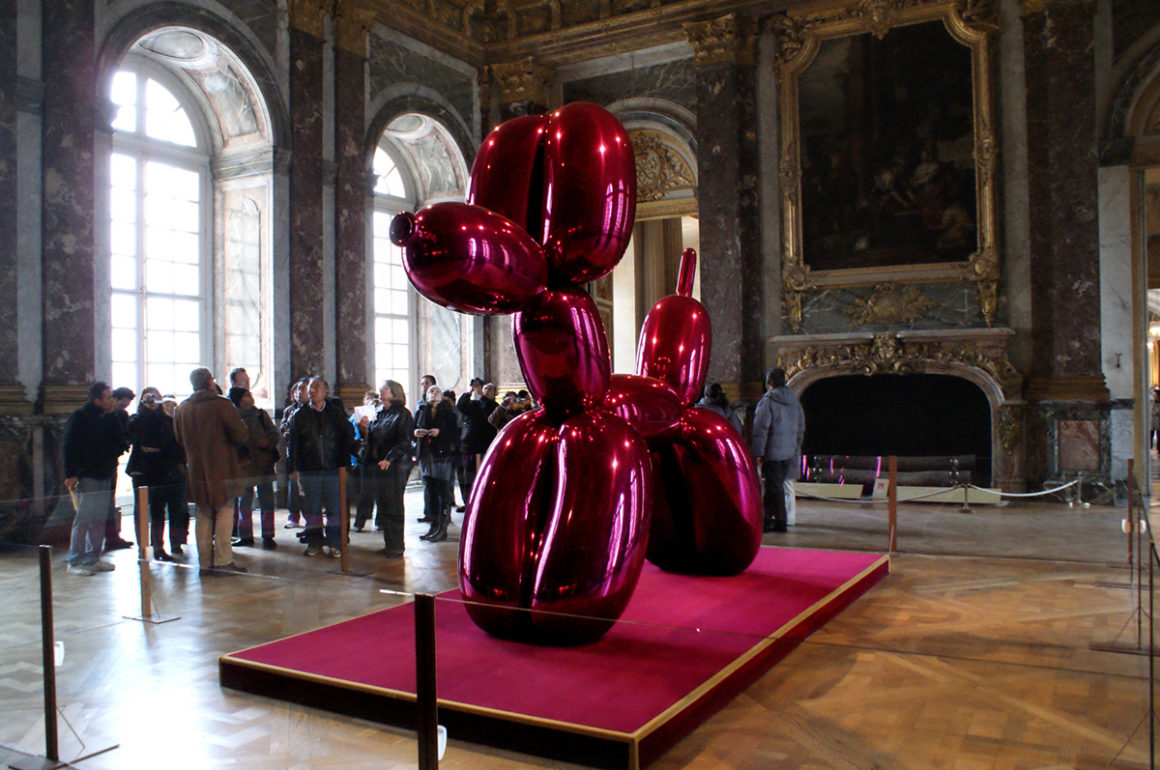

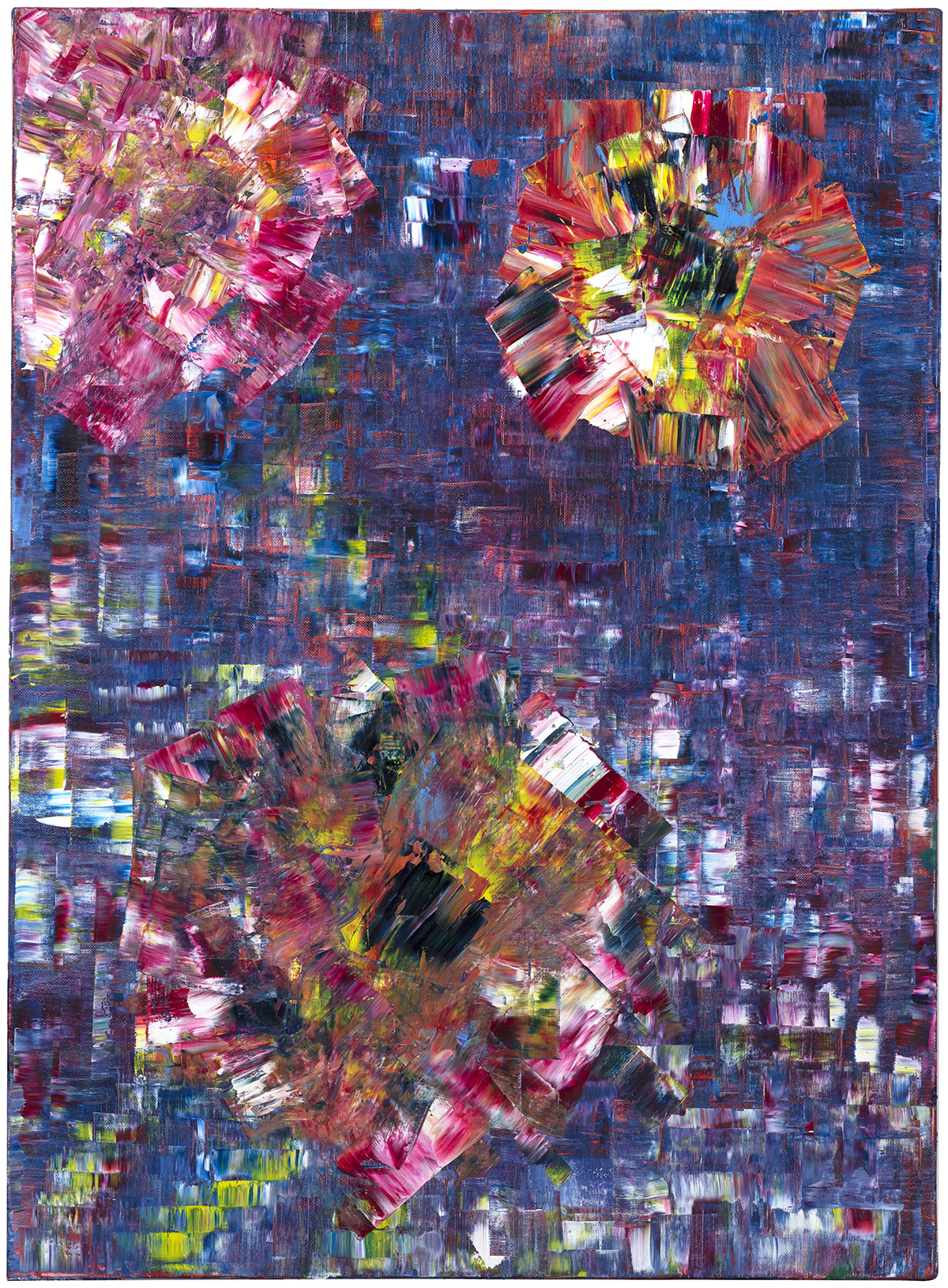

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Koons rose to fame in the 1980s, developing iconic works such as Michael Jackson and Bubbles (1988), the Made in Heaven (1990–1991) series, and Puppy (1992), which has been installed in Sydney Harbour, Bilbao, the Palace of Versailles, and Paris. While he’s most closely associated with his brightly coloured, shiny, oversized sculptures of kitschy souvenirs, toys, and ornaments (see his Celebration (1994–2011) series), Koons continues to seek new and surprising outlets for his creativity. In 2017, he teamed up with the luxury brand Louis Vuitton to produce an edition of bags printed with iconic European paintings, and more recently, he teamed up with high-street brand UNIQLO to create a line T-shirts and hoodies printed with some of most famous sculptures.

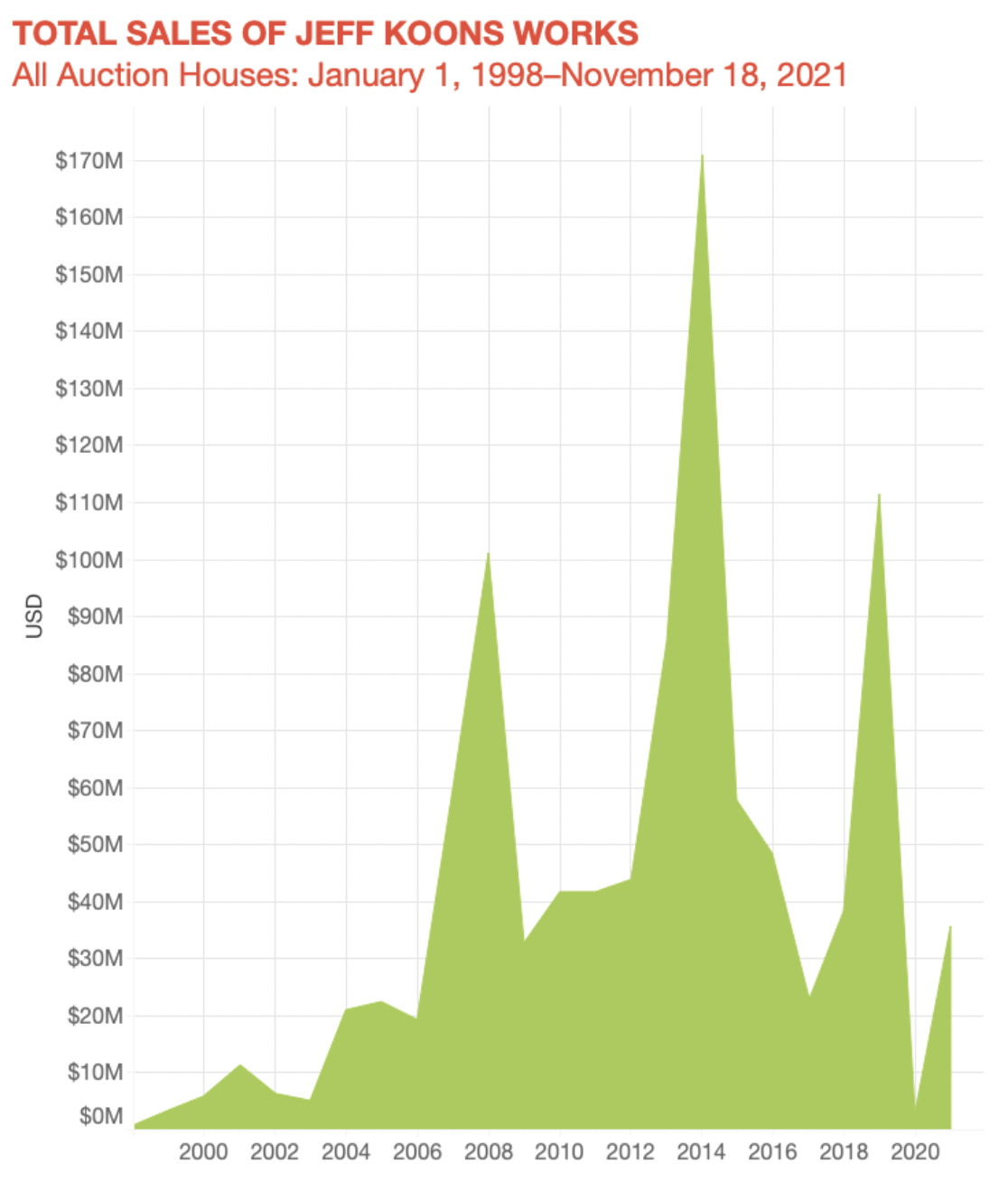

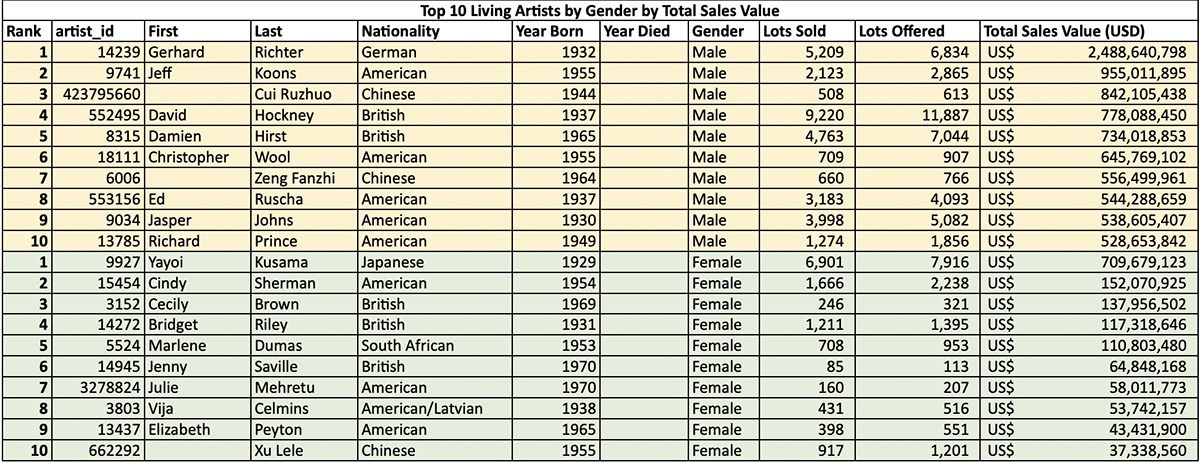

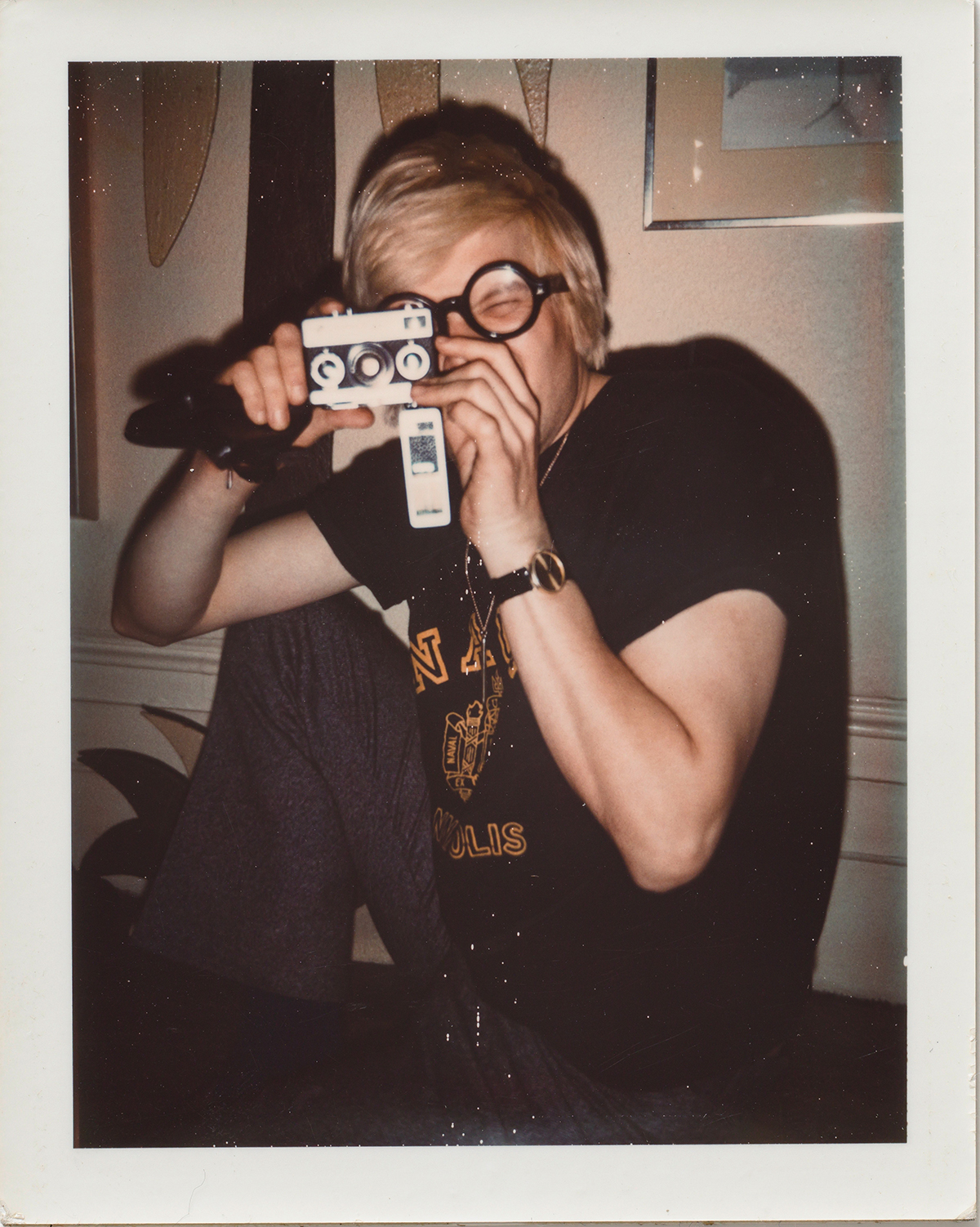

Courtesy of artnet

In 2019, his fame seemed to reach an all time high: Rabbit sold for a record-breaking $91.1 million at Christie’s auction house, making him the most expensive living artist. However, according to the artnet Price database, that single work accounted for the lion’s share of the artist’s $100 million (approx.) auction total that year. In fact, since peaking at more than $150 million in 2014, the artist’s overall auction volume has been slowly trending downward. In 2020, it was down to less than $3 million. While the pandemic undoubtedly played a role in the decrease of sales and things have picked up slightly since (to about $36 million to date) it’s still a far reach from earlier years. More worryingly, 48 (20%) of the 239 Koons lots offered this year at auction have failed to sell entirely.

Read our interview with Jeff Koons from the Autumn/Winter issue

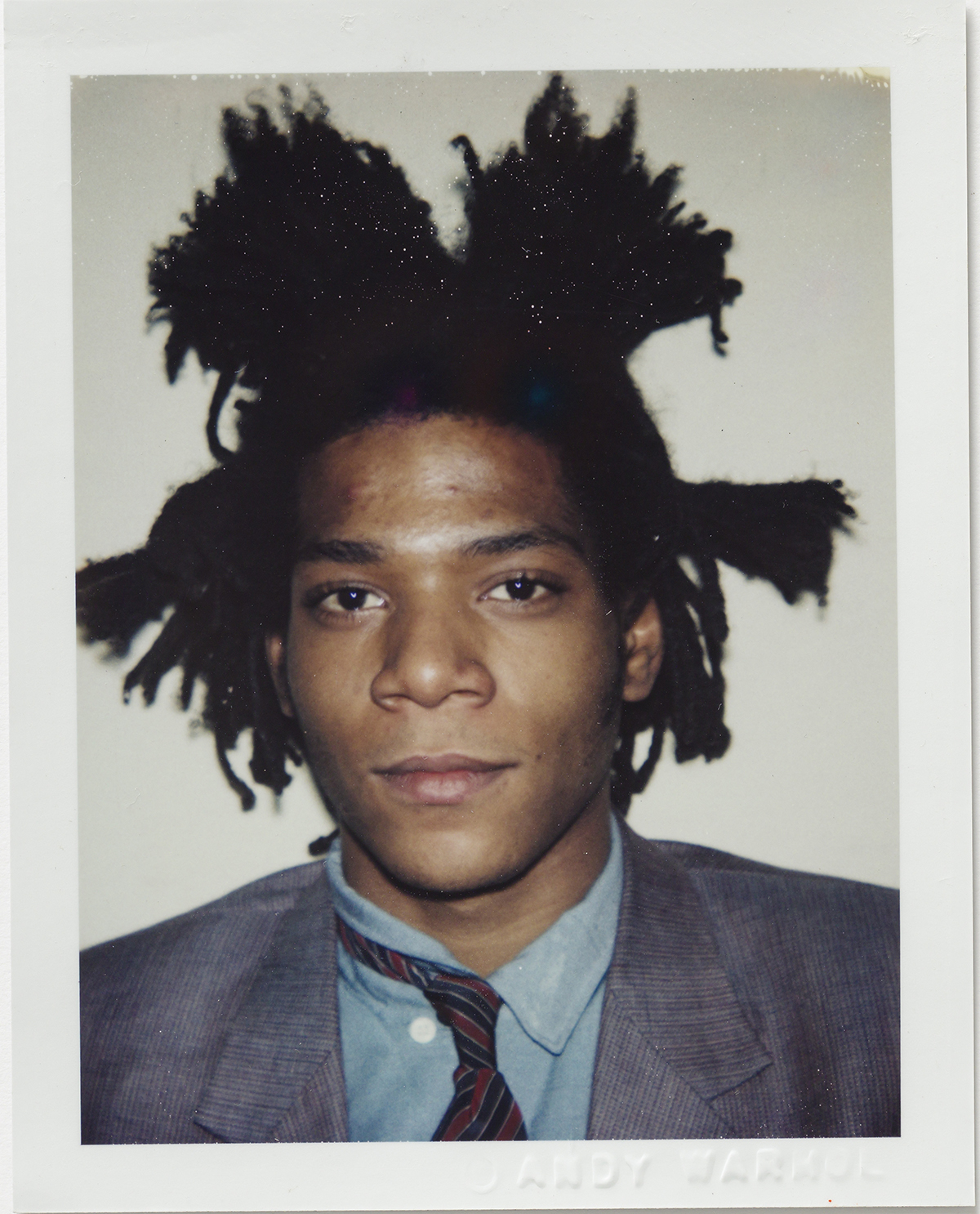

Over the past few years, major cultural shifts in the art world and beyond have contributed to the rather rapid depreciation of the Koons market. First and foremost, there has been a generational shift, with a new group of young collectors becoming the driving force behind the rise of Ultra Contemporary artists and a wider change in tastes. Peers of the BLM, MeToo, and climate change era, these young collectors are looking for more depth and meaning than Koons’ shiny kitsch seems able to offer. Quite possibly, the extravagant prices and controversial subject-matter (namely Koons’ Made in Heaven series which featured explicit images of his former wife, porn star Ilona Staller) have, ultimately, overshadowed his career, but this change can also be seen as a natural evolution. In fact, the only category in art that is more or less immune to changes in taste are the ultimate “trophies” that are so exceptional and rare in quality that anyone able or prepared to spend more than $100 million on a single artwork cannot afford not to go after them, if and when such works become available. Nearly everything else is and always will be affected by the evolution of culture.

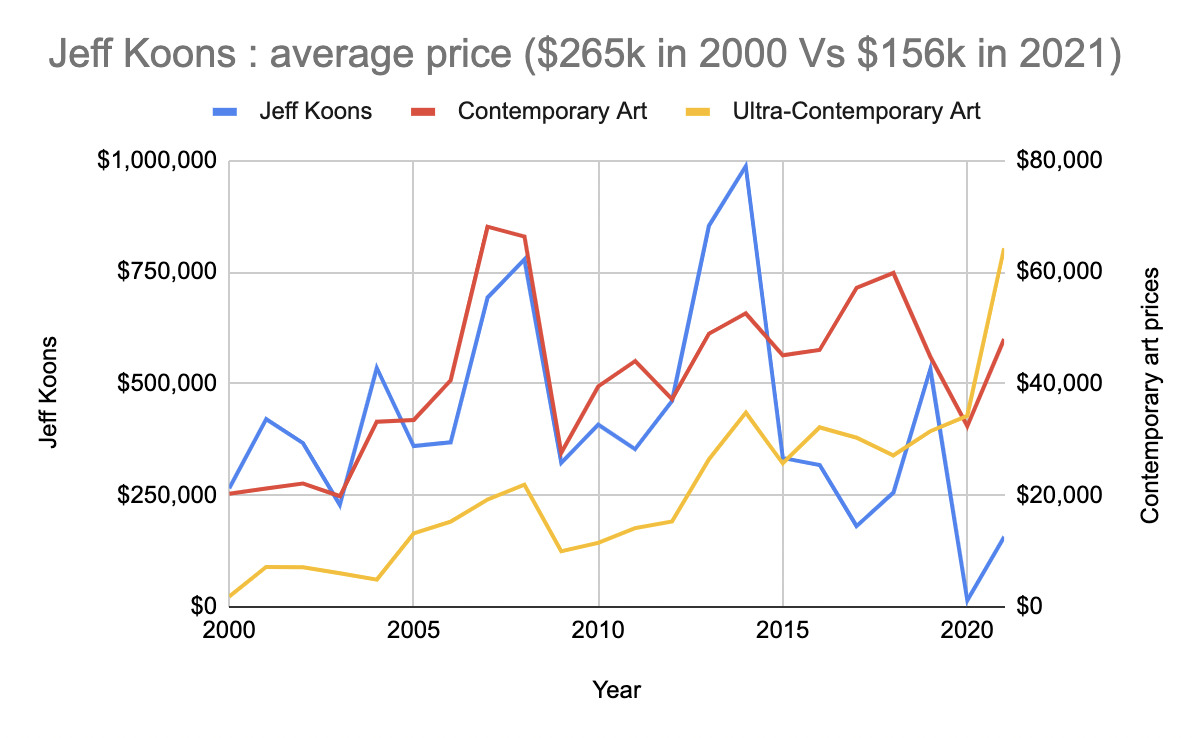

Courtesy of artnet

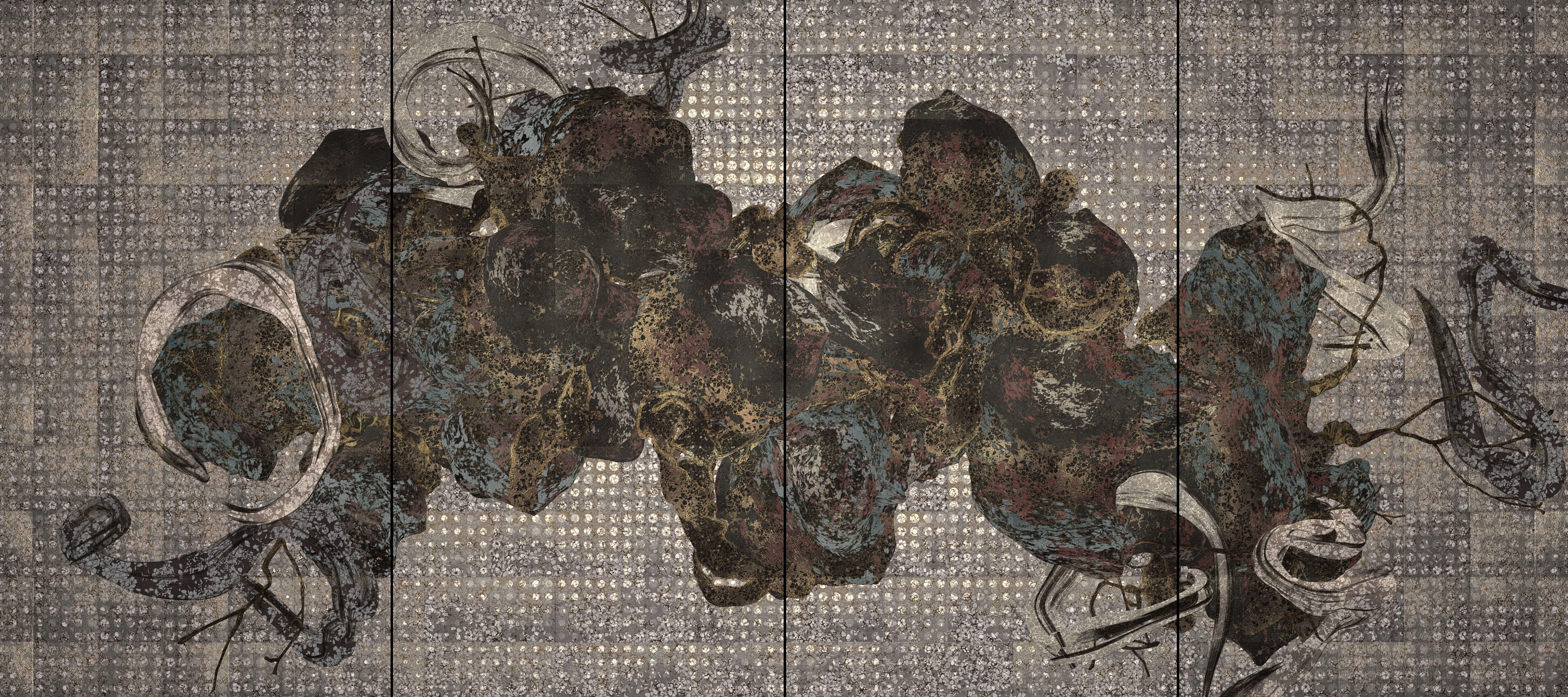

Additionally, and importantly, the health crisis of the past two years has had a profound impact on not only the art market, but also on the popularity of the hyped pre-pandemic artists. Internationally recognisable artists such as Richard Prince and Takashi Murakami have also seen a depreciation in their average prices at auction, indicating a decline in their popularity. Perhaps, this is because these figures are seen to be representative of a pre-pandemic era, an era which was more superficial and frothy than today’s.

Read more: The Best Art Exhibitions to See in January

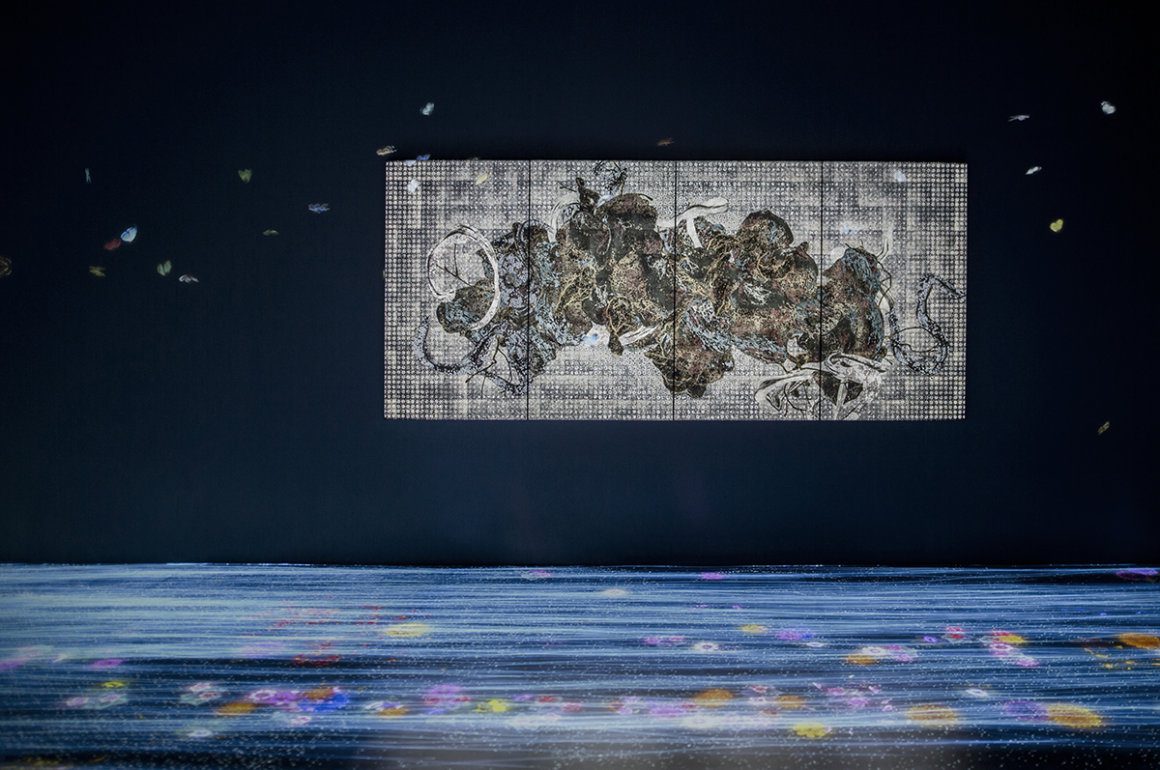

Koons currently ranks as number 57 in artnet’s list of the top 300 most popular artists, but if the market is anything to go by, he’s in danger of slipping off it altogether. “For me, at a certain point it became so much about the money that I couldn’t look at a shiny outdoor [Koons] sculpture without thinking about dollar signs,” commented American art advisor and specialist in modern and contemporary art Lisa Schiff. “When it becomes too much about the money, it’s just not interesting. I feel like where he started is somewhere very different from where he went.”

Now, Koons’ new dealers at Pace Gallery (the gallery announced exclusive representation of the artist in April after he left Gagosian and David Zwirner) are faced with the daunting task of rekindling his market. His latest works – stainless steel replicas of porcelain figurines – are set to appear in a solo show at Pace New York in late 2023 but only time will tell if the market can be swayed once more in his favour.

Sophie Neuendorf is Vice-President at artnet. Find out more: artnet.com

Recent Comments