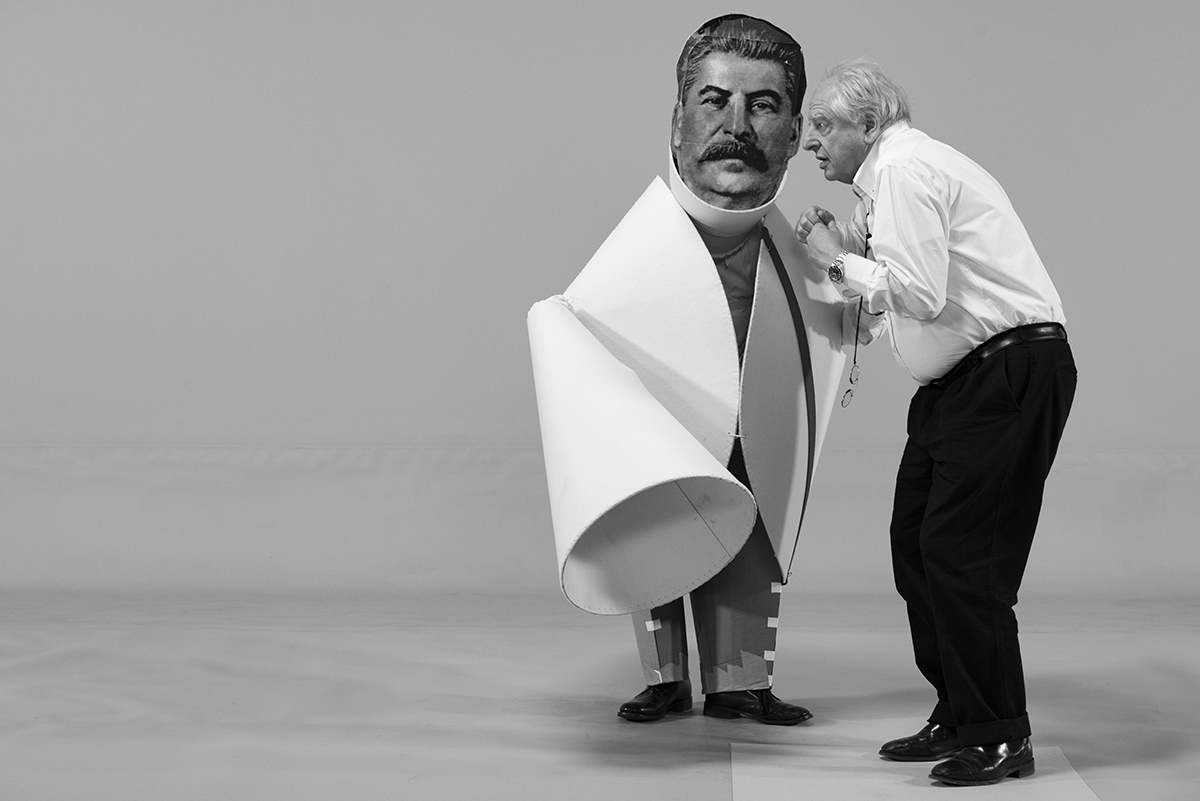

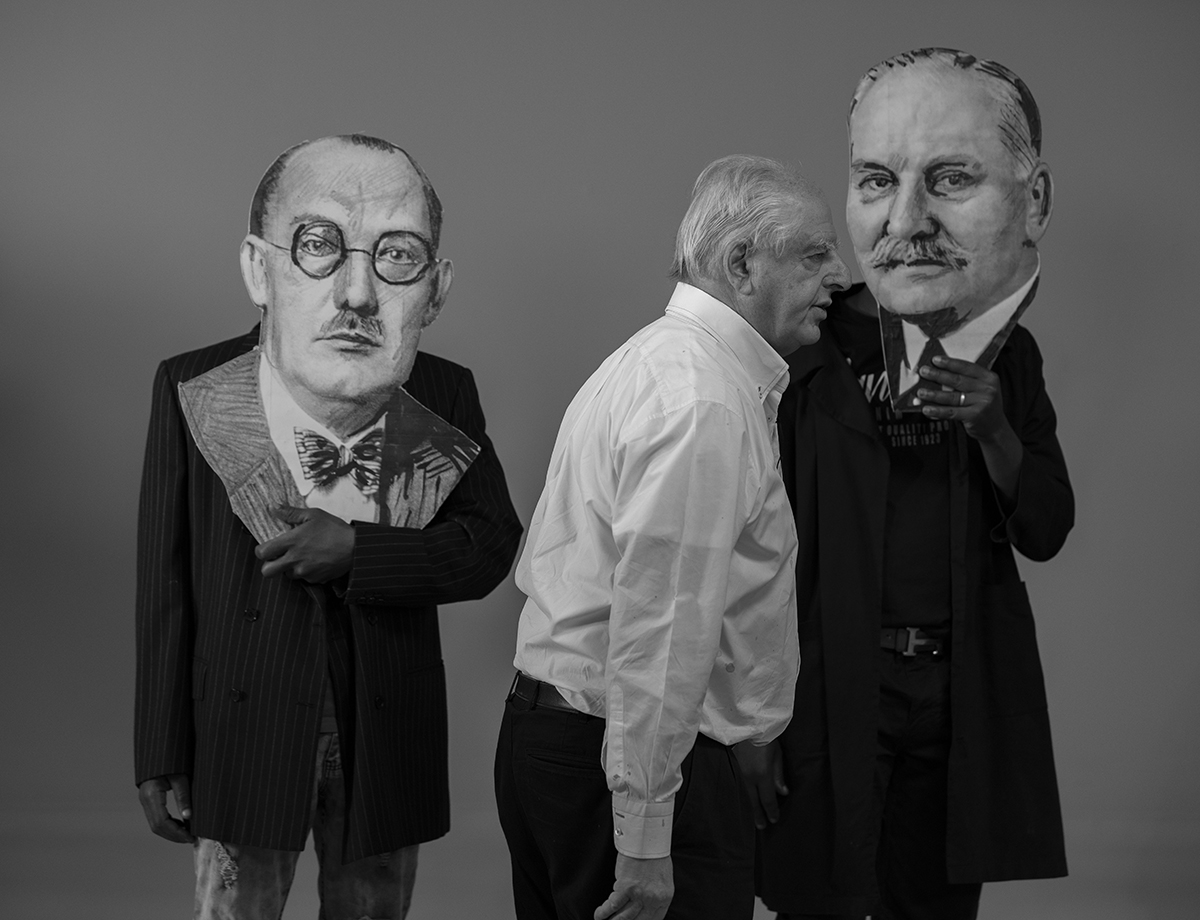

William Kentridge is one of the great artists to span the last century and this one. Recently the subject of solo retrospectives at the Royal Academy of Art in London and The Broad in LA, the South African maestro sits down with LUX Editor-in-Chief Darius Sanai to discuss extremism, absurdity and politics in art

Sitting with William Kentridge ahead of our interview, as an assistant takes our order for coffee and biscuits, I can’t help playing a little game with myself. What, I wonder, would I think the great artist did for a living, if I didn’t know already?

We are backstage at the Barbican Centre, London, in the staff canteen, a windowless space that is empty for the moment as it is mid-morning. We have seated ourselves at a small square table in a corner, beneath a couple of framed newspaper cuttings of theatre reviews. Kentridge is wearing a white collared shirt and navy round-neck sweater – as, coincidentally, am I. Well built, with plenty of white-grey hair, slightly tousled and prominent white eyebrows, distinguished and just a tad authoritarian in his demeanour, he gives the vibe of being a professional.

Maybe he is a lawyer, like his parents, two of the most celebrated human-rights lawyers in his native South Africa? His father, Sir Sydney Kentridge, represented Nelson Mandela at the Rivonia trial of 1964, at the height of the apartheid system, which saw the ANC leader jailed for 27 years for campaigning for racial equality. Sydney, now 100, only retired in 2013 at the age of 90. William’s mother, Felicia, who died in 2015, founded South Africa’s Legal Resources Centre, which gave legal aid to those being prosecuted by the apartheid state.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

But no; William Kentridge looks like a doctor. That’s it. I feel like I’m sitting with a veteran family doctor, a GP who has seen years of woes and is used to answering the same questions over and over. There’s his dryness, the sense that his mind has experienced the best and worst of humanity, his ability to anticipate a question and have an answer ready, delivered in a highly articulate, slightly deadpan way.

My silly thought exercise is no more than that. Artists come in types as varied as humanity itself. And I already know that Kentridge comes from a highly learned, cultured family of Jewish humanist professionals. But still, it does connect with something else: the breadth of knowledge, reading and intellect that is packed into Kentridge’s works.

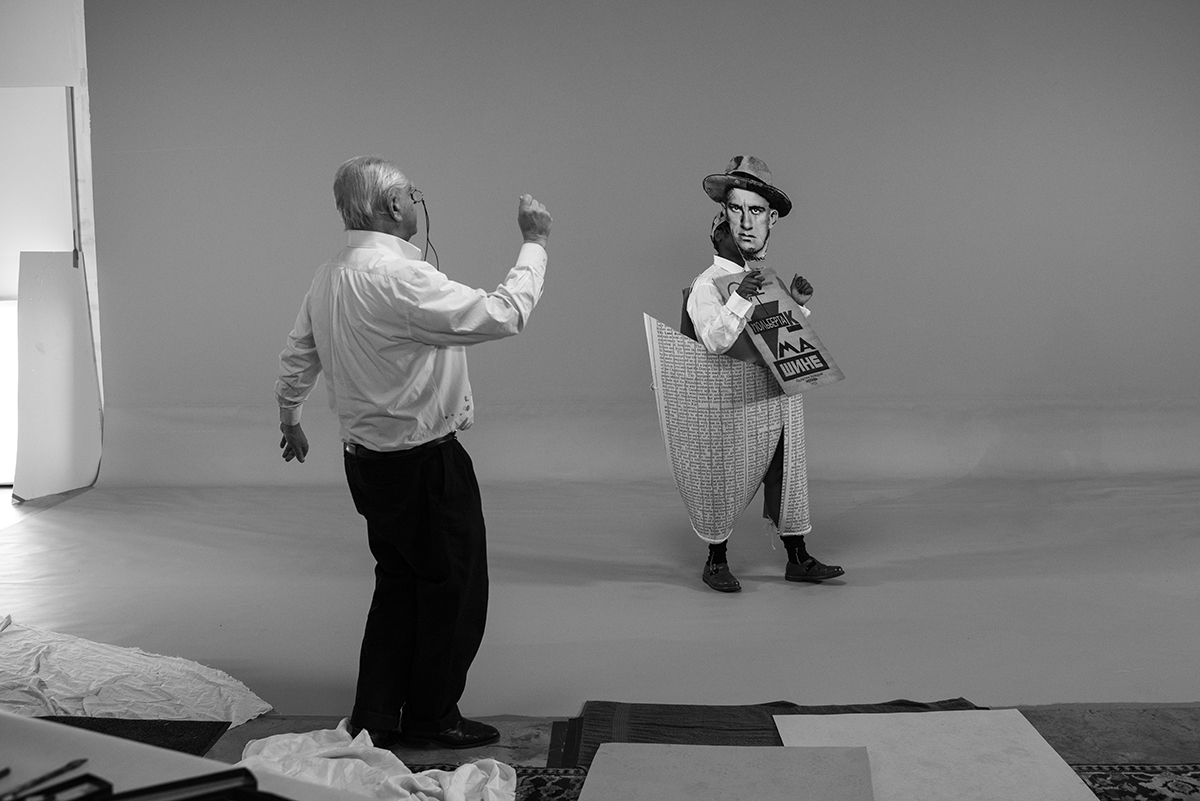

In many ways, this old white heterosexual male (by current societal definitions), with a specialism in charcoal drawings, is an unlikely global artist of the moment. His show was the centrepiece of the Royal Academy of Arts in London last autumn, and he had a similar solo show at the equally prestigious The Broad in Los Angeles after that. Much of the political and societal challenges he explores are from the last century: apartheid, the Soviet Union. Kentridge himself is 68 this year.

And yet his works, which range from charcoals to animations, vast tapestries to sculptures, theatre shows to his poster-like rubrics, have never had more relevance in a world where the absurd is becoming integrated into the cultural norm, and where the Enlightenment liberal humanism he displays is being sidelined by winds of unreason.

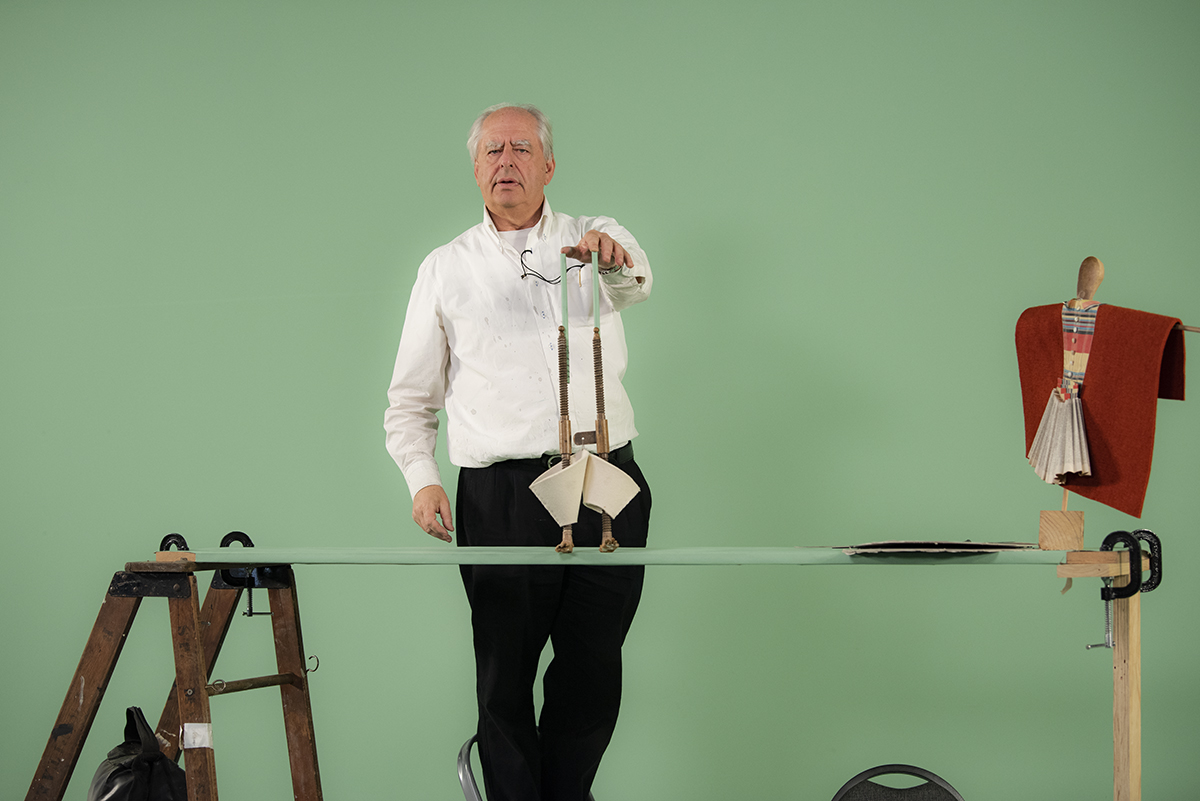

Coffee delivered and biscuits to hand (which are being nibbled at by Kentridge), I ask him exactly what type of artist he is. He is famous for his charcoal drawings, but he also creates stop-motion videos, animations, tapestries, opera and theatre productions, operatic films, operatic historic films… we are meeting at the Barbican because he is directing a series of short diverse performances here, developed by artists at his The Centre for the Less Good Idea in Johannesburg, which would, I tell him, for the uninformed viewer seem like quite a different art form to drawings. How would he explain what he does, in a nutshell, say to an ancestor from 100 years ago?

“I would say I make drawings, which would be familiar from 100 years ago. Sometimes those drawings are set in motion as animated film, so, if we’re in the 1890s they might have recognised that. Sometimes those projected images are used as backgrounds for theatre performances, which they would have known from 18th-century theatre-projection techniques. And so sometimes they shift between drawing and animation and theatre production and sculpture. But they all start off as drawing. Drawing is the heart of it. Even if it’s working with an actor onstage, the logic is that of making a drawing.”

There is a precision in his answer, almost jarring with its immediacy. He gives thoughtful answers but doesn’t seem to take time to think – a sign of a sharp mind.

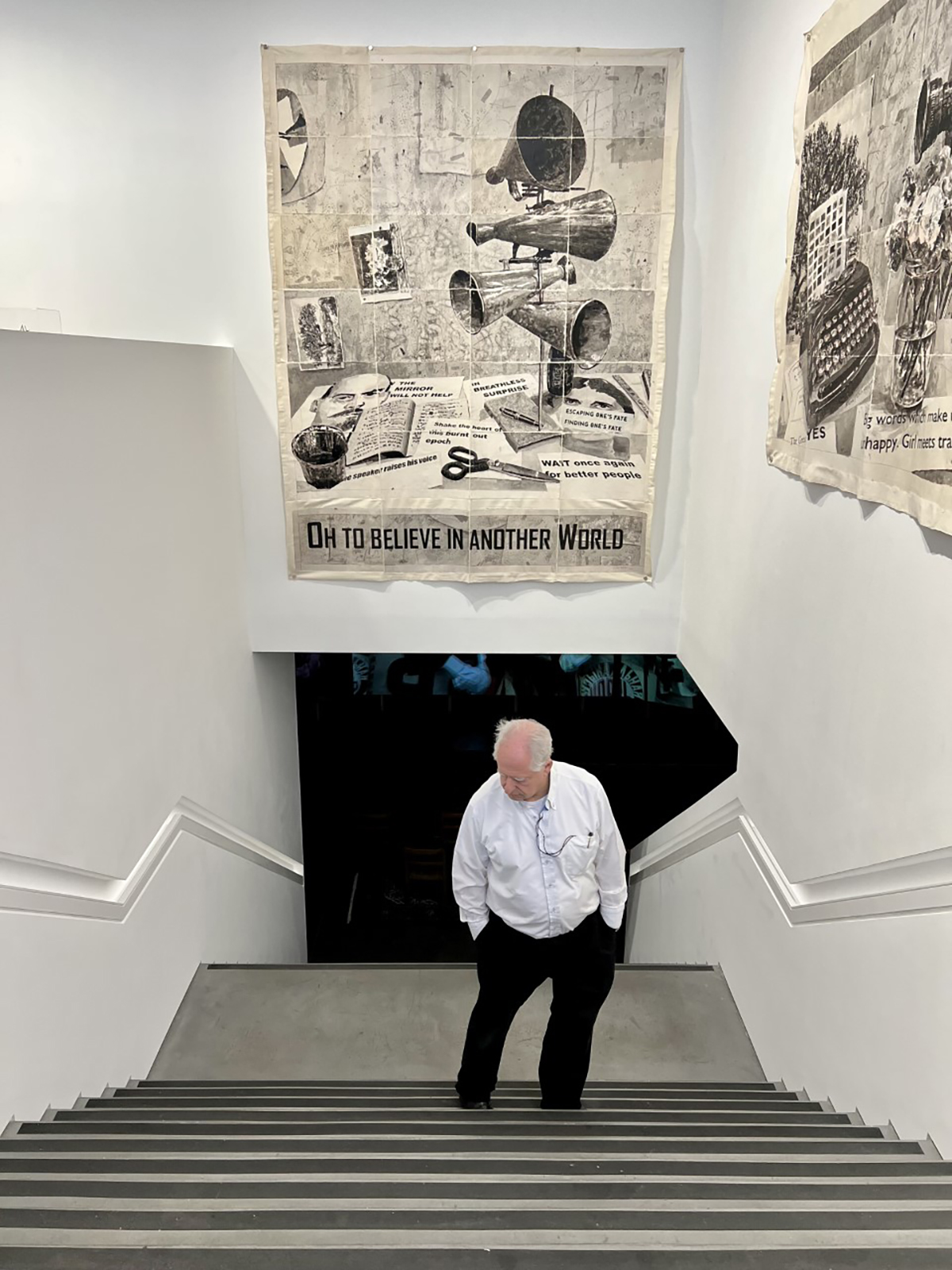

Walk around one of Kentridge’s grand retrospectives, like the one at the RA, or the simultaneous selling show, “Oh To Believe in Another World”, around the corner at Goodman Gallery in Mayfair, and you immediately notice how prominent the themes of politics and society are in his works. At the RA, a 1997 animation playing on a loop, Ubu Tells the Truth, referred to the horrors of apartheid South Africa, including state-sponsored murders. In Goodman Gallery, we saw glimpses of the brutality of Soviet communism in his latest film (of the same name as the exhibition) and other works.

And yet there is a feeling that Kentridge, while amplifying these extremes of negative humanity, is not ideological himself, not campaigning for some political end. “No, it’s not ideological,” he agrees, referring to “Oh To Believe in Another World”. “What it is, is saying, ‘Here are the paradoxes’; that something that started with such optimism descended into such instrumental brutality. And so it sets the question of how does one find emancipation? We understand that it’s not okay for the inequalities in the world to exist, but that some of the huge-scale plans to change that have really not worked.

Illustration by Jonathan Newhouse

“That’s the paradox it sets itself in. More specifically, how did Shostakovich navigate his way through the Soviet Union? How did an artist do it? It’s a mixture between making a space for anarchic stupidity and learning from what you do, rather than telling the world what it has to do.”

Speaking with Kentridge, you soon realise that every answer gives rise to another question, which is perhaps an allegory for artistic inspiration. I ask, for example, whether he is commenting on events in these works.

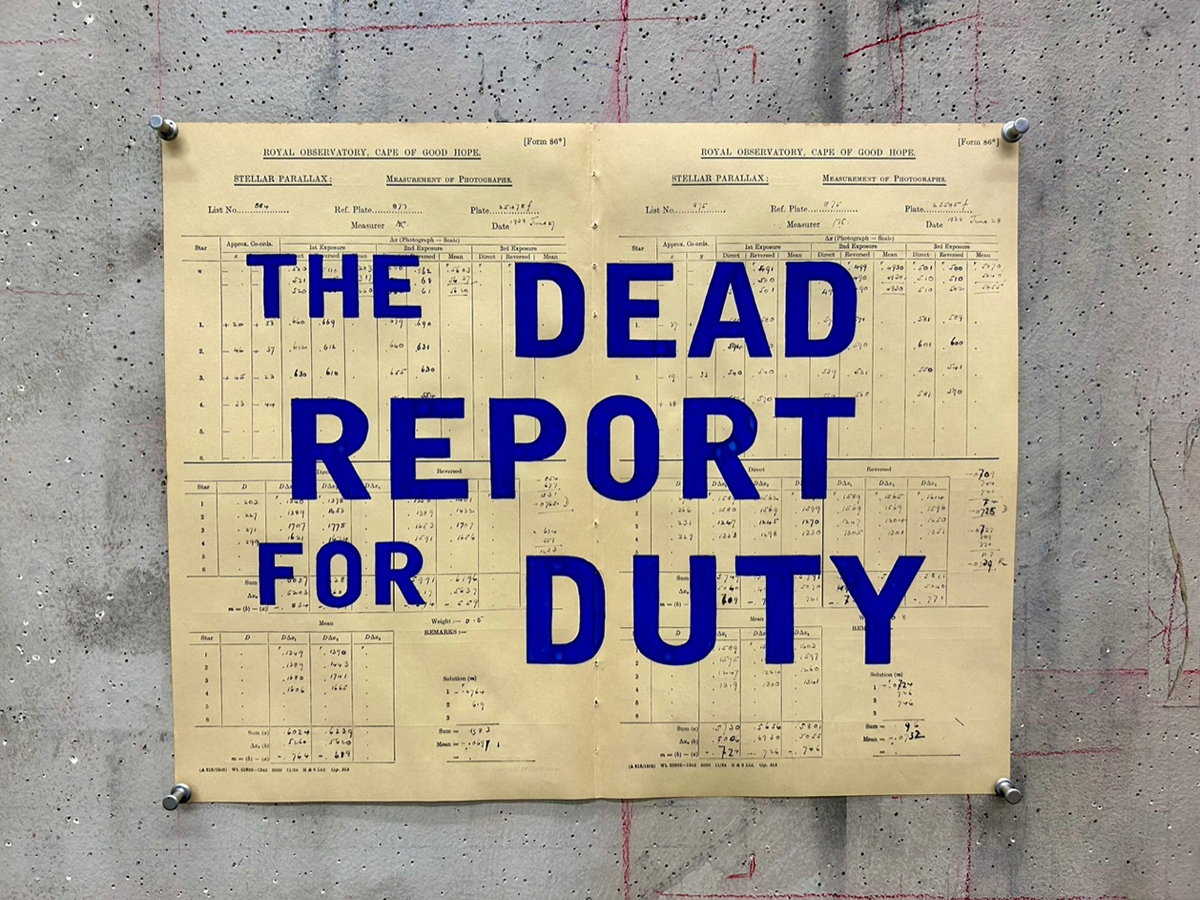

William Kentridge created the artwork The Dead Report For Duty, for this issue of LUX

“I don’t see it as a commentary,” he says, “because in a commentary you need a sense of what your comment is at the beginning. At the end we discover what it is we have made. For me, the most interesting artworks are the ones that end with a riddle. You know a riddle is the edge of knowing a meaning and you can’t quite put your finger on the right word, exactly what it is, and then you become complicit in trying to construct what it is, to fill the gaps, to leap over the gaps, and that’s the place where we are. One of the phrases that comes up is, ‘There is no good solution’. There are less bad ones, though.”

So am I correct to see a kind of dark, absurdist wit in these works, despite, or perhaps because of their subject matter: apartheid, communism in the Soviet Union and the Cultural Revolution in communist China?

“Well, there’s certainly an absurdism,” he says, and then qualifies it. “In England, the absurd often just means the silly or funny. I mention the absurd as a logic that has gone astray, and then following that bad logic with complete clarity and assiduity. And if you think of what apartheid was in South Africa, it was absurd. We decide who you are by whether a pencil will stick in your hair or not, and that will determine your future. So there’s an absurdity in that, but it gets followed through with all the violence of the state behind it. It would be impossible to describe what happened in South Africa without invoking the category of the absurd, so I find it a very central way of thinking. It’s also about giving an image the benefit of the doubt – doing it and seeing what happens. And that would be like in psychoanalysis, where you use free association on the basis that something may well come out, even if you don’t know what it is in advance.”

I mention, as context, that I feel I can understand his works a little because I studied Soviet history, and worked in post-apartheid South Africa as a foreign correspondent. Do people viewing his works need this kind of knowledge?

“Hmm,” he ponders briefly. “It’s like in one of the films at the RA, where there’s an image of headphone speakers put on a pig’s head, and then the pig’s head is exploded. If you’re from South Africa, then you’ll know that was actually an experiment done by the security police to check boobytrapped headphones – they put them on a pig’s head and blew the head up. If you don’t know that story, it’s nonetheless an image of extreme violence, dichotomies and the vulgarity of putting Walkman headphones on a pig and then blowing it up.

“I think people are very good at creating or either understanding or constructing a context – which may not be that accurate, but nonetheless fulfils us. So I don’t believe that you have to understand all the context. But it helps to understand what apartheid was, to understand there was a cultural revolution in China.”

I wonder what he thinks of the current cultural battles and universalisation of identity in the Global North. Identity was, after all, the basis of apartheid, its justification for an institutionalised racial categorisation that put white people at the top, black people at the bottom, and so-labelled “coloureds” and “Indians” somewhere in the middle – although, effectively, near the bottom. I mention that when I worked as a foreign correspondent in the 1990s, the only times I had been required to state exactly what race I was on a form, were in apartheid South Africa and left-wing councils in the UK.

Do these conversations come into play in his works? His answer is, typically, a deep one that slides into a riddle before it quite gets to its point. “Not directly, but I think they do come into it. I mean, there’s a polemic against an identity politics in the world, both in the way I work with different people and in the way that if you say, like in South Africa, we had all those years of apartheid, of identity politics, black people must live here physically, this is the type of music they can listen to, white people can listen to classical music, black people must listen to jazz.

“Part of the struggle against apartheid is saying, ‘No, a black person can listen to opera, can be an opera singer.’ So there is a polemic in that. There’s a polemic in saying, ‘Why do you do it – art that is connected to politics, without it having a political message?’ It says it clearly: politics is much less clear cut, much more paradoxical, ambiguous. Much less certain.”

We turn briefly to the politics of South Africa, where the institutionalised brutality of the apartheid era briefly gave way to hope when Nelson Mandela became President in 1994, and has now degenerated into corruption and mismanagement. Is he pessimistic?

“I always feel that in South Africa to be an optimist or a pessimist is wrong, because there were two futures unfolding, an optimistic one and a pessimistic one, but the difficult future feels harder to escape. I made a film called In Defence of Optimism, which is about life in the studio: what is the optimism in here, in making something, in not leaving the paper blank, in resisting entropy? And that became a strong action rather than a theme. Downtown in Johannesburg, shockingly, they have seven hours a day without electricity, sometimes two days at a time with no water. So it means that the well-off have a generator, they have a 4 x 4 vehicle that can go over the potholes in the road, but if you’re anyone else your life is really, really difficult and messed up.”

But he is loyal. He is still there. “I am still there. And two of our three children are there. But so many of the collaborators, musicians, actors, are still there – that’s a strong pull. I would feel quite dislocated, I think, if I moved. In a way, I stay in South Africa because I don’t have to. Also, it is depressing when things are falling apart, but it’s a very interesting place to be. It would be interesting to see, when you see the whole series of performances, whether it’s, ‘Oh, my God, I’m just going to go home and slit my throat’, or whether it actually gives energy.”

Is he disappointed in the ANC – once banned under apartheid but which has governed South Africa since 1994, and has, post-Mandela, proved such a poor governor? “Yes, I think we really messed up badly in the years of the Zuma presidency [2009-18]. And it’s difficult to get out of it – our new president hasn’t done much better.”

I say that I remember Cyril Ramaphosa, whose current presidency has been marked by corruption and mismanagement scandals, when he was an ANC negotiator in the optimistic years of the 1990s: he seemed like a perfect future president – wise, thoughtful, considered. “He was, and everyone kept giving him the benefit of the doubt, saying, ‘It just takes time, it just takes time’, but now it’s been many years.”

Read more: Christopher Cowdray on the Dorchester London’s Latest Renovation

Kentridge doesn’t give much away, but you cannot create monumental, moving works like his (and the occasional funny ones) without a big emotional burden. I ask, is drawing therapeutic?

“Drawing is completely therapeutic,” he says. “However bad I’m feeling, after two hours in the studio just quietly drawing, everything seems manageable.”

At that point, the powerful intellectual sitting next to me sounds, briefly, like any vulnerable, creative artist.

Portraiture and exhibition photography by Maryam Eisler

Find out more: kentridge.studio

This article was first published in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of LUX