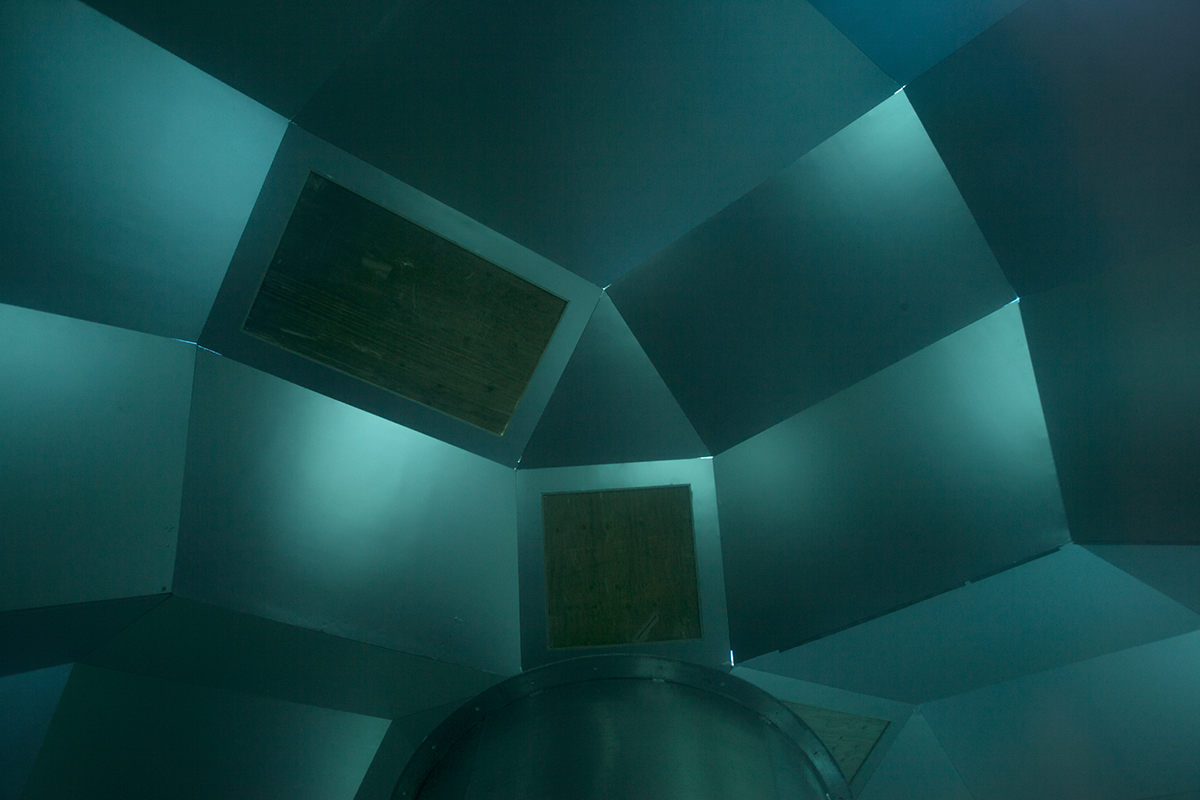

Construction view of Los Angeles Water School (LAWS) (2018) by Oscar Tuazon

Artists have long explored themes of environmental sustainability in Southern California, but a recent series of devastating wildfires has brought even greater resonance to their work. Evan Moffitt explores how four LA artists are changing the way we think about climate change

DEUTSCHE BANK WEALTH MANAGEMENT x LUX

When the Getty Fire tore up the dry hills of Mandeville Canyon in October 2019, many in Los Angeles feared the worst: the Getty Center’s Titian and Thomas Gainsborough paintings curling from their frames, masterworks of European art reduced to cinders. This wasn’t the first time locals had imagined such a catastrophe – Ed Ruscha had painted his iconoclastic portrait of the county museum, The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire, in 1968 – but this time, it was different. The severity and frequency of wildfires had increased as climate change accelerated, threatening not just art in Southern California but the very way of life there.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Scientists, furthermore, have warned that the city could eventually run dry, and nothing has shaped LA more than its lack of water. The Department of Water and Power was long seen as the most powerful bureau of city government, dating back to when William Mulholland drained the Owens Valley in 1913 to soak the dry fields of San Fernando. The violent conflict that ensued was famously fictionalized in the 1974 film Chinatown, and many artists have explored the city’s relationship with water, from Judy Baca’s epic mural along the Tujunga Wash, The Great Wall of Los Angeles (1974–84), to more recent projects by artists such as Carolina Caycedo and Oscar Tuazon.

This work can be difficult, but it has struck an important nerve. “Most of our patrons are museums or their supporters who want to engage in dialogue with challenging contemporary art,” says Kibum Kim of Commonwealth and Council, the gallery that represents Caycedo. “They don’t want something that is easy.” For Caycedo, this has led to being included in shows at major institutions such as the Hammer Museum in LA, as well as having works in a number of private collections. Artists such as her are a reminder that Southern California has always been a place where artists, writers, filmmakers and others have mobilized around difficult issues, mining the past to build a better future.

Wagon Station encampment at A-Z West (2004) by Andrea Zittel

No one embodies the utopian spirit of LA more than Andrea Zittel. In 2000, the artist left a burgeoning career in New York for a ramshackle bungalow on the outskirts of Joshua Tree National Park. She began slowly expanding her compound in the desert, informed, in part, by the Bauhaus, Japanese architecture, minimalist sculpture and architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West. A-Z West, as the 60-acre campus is known, encompasses Zittel’s home and studio, guest cabins, outdoor sculptural installations, informal classrooms and a series of Wagon Stations, tiny chrome sleeping pods nestled between boulders like UFOs.

Read more: Picasso Through the Lens of David Douglas Duncan at Hauser & Wirth in Gstaad

Zittel refers to A-Z West as “an evolving testing ground for living – a place in which space, objects, and acts of living all intertwine in a single ongoing investigation into what it means to exist and participate in our culture today.” In part, this means creative, sustainable approaches to the privations of living in the desert. Zittel pulps her paper waste and sets it to dry in metal trays called the Regenerating Field; she uses the results to make sculptures. Vegetables grow from barrels shrouded by mosquito netting in a courtyard formed by shipping containers. Shade is provided by trees watered using dry irrigation techniques.

Installation view of ‘Rafa Esparza: Staring at the Sun’ at Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, 2019

What ecological problems might be solved by building better? Like A-Z West, Oscar Tuazon poses this question with his Water School (2016). Its central component, Zome Alloy (2016), borrows its bubble-like plywood structure from the waste-free dome homes designed in the 1960s by Steve Baer, the inventor of passive solar technology. Tuazon’s project also refers to another LA visionary, the architect Buckminster Fuller, best known for his transparent geodesic greenhouses and light-filled homes. When Zome Alloy was recently on view in the Chicago Architecture Biennial, visitors could browse a small library of books about water rights and convene for bimonthly discussions.

Read more: Gaggenau’s head of design Sven Baacke on the meaning of luxury

For several years, Caycedo has explored the effects of colonialism and industrialization on water resources throughout Latin America with her ongoing project ‘BE DAMMED’. At the 2016 São Paulo Biennial, four enormous satellite images of controversial Brazilian dams revealed the structures’ disastrous effects on the surrounding landscape. Caycedo hung brightly colored sculptures woven from fishing nets, which she calls Cosmotarrayas, mesmerizing mobiles linking the precariousness of marine resources to the over-fishing that threatens the life within them. “There’s been great demand for Carolina’s Cosmotarrayas, which have immediate visual power,” says Kim. “They’re colorful, and they play into generally accepted ideas about sculptural composition and form. But they also carry a powerful message.” Caycedo says she doesn’t believe in sustainability, per se: “Extraction will never be sustainable. A coal mine is not sustainable. The way we use our water is not sustainable. I prefer to think about ‘sustenance’ in terms of my work and a healthier relationship to nature: to give strength to something you care about or someone you love.”

Installation view of ‘Wanaawna, Rio Hondo, and Other Spirits’ (2019) by Carolina Caycedo at Orange County Museum of Art, Santa Ana, CA

In 2014, artist Rafa Esparza began making adobe bricks from mud he harvested on the banks of the Los Angeles River, on a parcel of land known as the Bowtie – one of the only sections of the river left unpaved by the Army Corps of Engineers when they buried the channel in concrete in 1936. In 2014 the artist Michael Parker had carved a 42m obelisk into the earth that Esparza covered with approximately 1,400 of his bricks. During the installation’s closing performance, he donned a traditional Aztec loincloth, pheasant headdress and ankle rattles and performed a dance atop the structure that referred both to his ancestral people and the indigenous Tongva displaced from the river’s edge by colonialism. Adobe and thatch are among the most sustainable building practices on earth, but the indigenous people who used them were killed or forced from their land, which was then torn up to build LA. Esparza has since repurposed his bricks for shows, including at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in what he refers to as “browning the white cube”.

This has had its challenges, according to Kim, who represents Esparza: “Adobe is very structurally strong, but it’s not archival; it will deteriorate over time, which can be hard for some collectors and institutions to accept. But that’s an important element of Rafa’s work: we need to re-conceive our notion of art as a static thing that will forever remain the same.” By imagining cities like LA and their museums made of mud and river water, Esparza places the environmental costs of colonialism into stark relief, proposing, if not a return to a precolonial past, at least a few important lessons we might learn from.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2020 Issue.