Rashid Johnson in the studio with a work from his series Anxious Red Paintings. Photograph by Sheree Hovsepian

Rashid Johnson is a cult superstar among contemporary artists, inexorably leading the cultural narrative. His wife Sheree Hovsepian, herself an acclaimed artist, photographs him for LUX at their New York home, while Millie Walton speaks with him about culture, identity and the future

Chicago-born artist Rashid Johnson is on his ‘daily constitutional’ around his neighbourhood in Long Island, New York where he lives with his wife Sheree Hovsepian (also an artist), and his son Julius. We’re speaking on the phone and occasionally, the whoosh of passing cars, birdsong and the artist’s breathing filter down through the speaker. As for many of us during lockdown, walking has become a vital addition to the artist’s daily routine that normally involves him being in the studio from 9am until 3pm.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

During those hours, Johnson says he is not always actively making art, but it is the time he commits to “laying [his] creativity bare… you can’t just wait for it to happen, you have to show up and work. I get a lot of joy from making art, and I say joy specifically because I don’t really know how to participate with happiness or what that is, but I also experience a lot of frustration and disappointment. All of those things feed into my project and why I’m doing it.”

Portrait of Rashid Johnson by Sheree Hovsepian

I wonder how this period of prolonged confinement, reduced travel and fewer physical exhibitions has affected him. “I feel like I’ve been crazy busy,” he says, “in both making artworks and doing a lot of talks and community engagement projects, but I’ve also spent a lot of time with family. I feel like I’ve learnt a lot from watching them so closely.”

Johnson is one of the most influential of contemporary American artists. He is a cult figure, in fact, among many collectors and others in the art world who see him as the voice of a generation and a commentator on the issues of race and social upheaval.

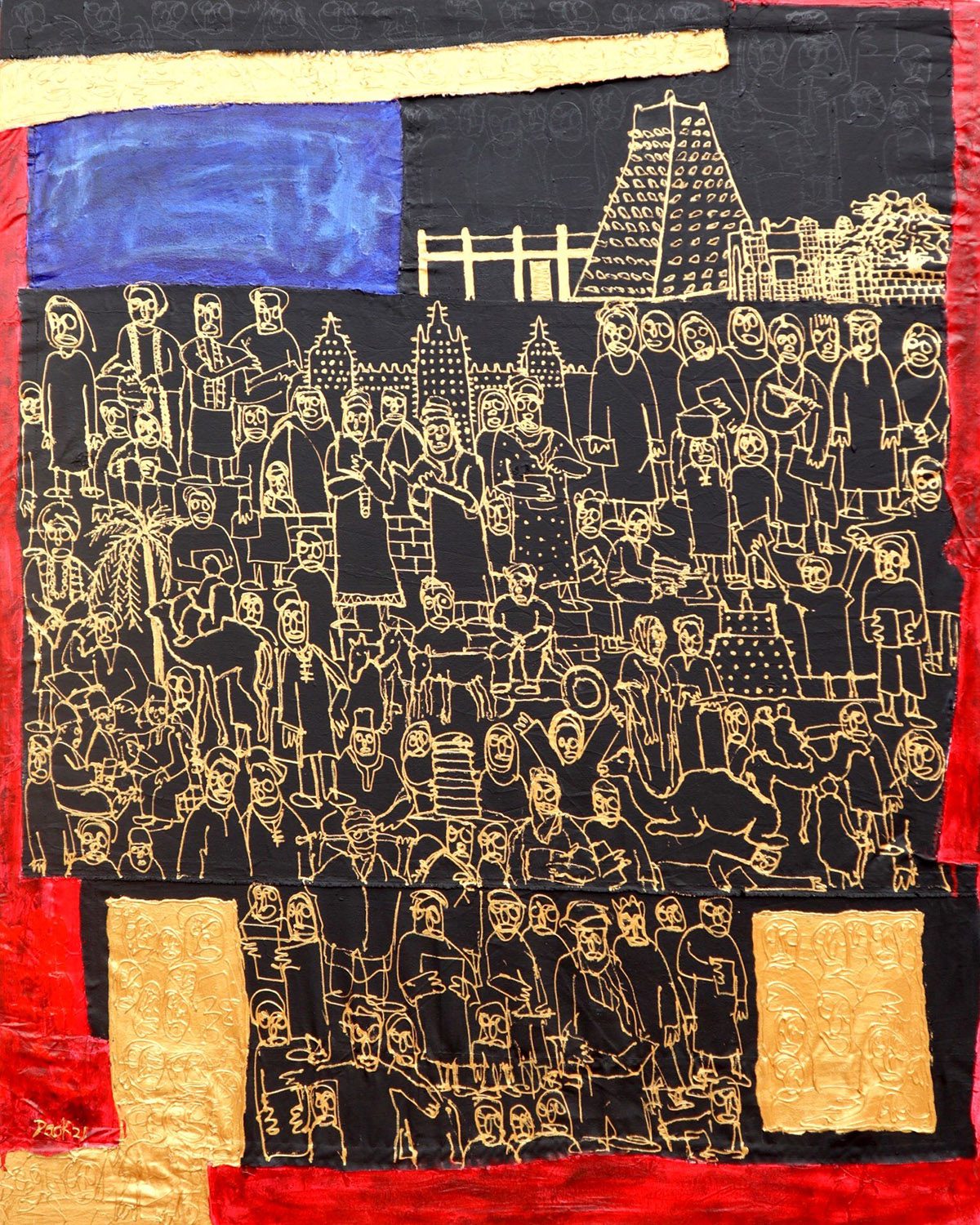

From right to left: Untitled Anxious Audience (2016) detail; Fatherhood (2015) by Rashid Johnson. © Rashid Johnson and courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Johnson found early success following his inclusion at the age of 24 in the celebrated group exhibition ‘Freestyle’, at the Studio Museum in Harlem. His intimate portraits of homeless black men taken with a large-format camera immediately grabbed the attention of both the art world and the wider public. Since then, the 44-year-old artist has racked up an impressive list of solo museum shows and commissions, including a major project for the atrium at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow and, most recently, an installation at MoMA PS1 in New York entitled Stage (on view until autumn 2021), which comprises five microphones standing at different heights on a raised platform. There are references to protest and public oratory in this work, and also to hip-hop culture (a recurring influence on Johnson’s practice). The microphones are available for anyone to use; their words will be recorded, archived and, occasionally, broadcast via the museum’s website. The use of everyday objects is familiar Johnson territory, but the installation’s straightforward simplicity and direct call to action mark a new direction.

Read more: Artists to watch in 2021 – Arghavan Khosravi

As a black male artist, Johnson’s work is inevitably being seen in the context of the protests following the killing of George Floyd. This might risk an over-simplified or less nuanced interpretation of his work. When asked about this, he’s patient, self-analytical, and explains carefully his way of thinking. “[My work] is about how I identify and how I’ve grown in that identification – both realising when I should consider the collective nature of being a man, a black man, an American and a man in his forties, and also getting really granular with it: what are my obstacles? Which aspects of my life am I most interested in talking about? What are my character defects, and how do I start the process of unpacking some of those?”

From right to left: Falling Man (2015); and Standing Broken Men (2020) by Rashid Johnson. © Rashid Johnson and courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Has he ever felt under pressure to make a certain type of art? “No, but I knew that when I made decisions they were going to be interpreted in a certain way,” he says. “Oftentimes, as an artist of colour, in particular a Black American artist, people imagine that the effects of racism and slavery and other oppressive aspects of our history reflect on me and my project in specific ways, but what I’m really interested in is how those more monolithic racial concerns are filtered through someone like me. I’m searching for autonomy, which I think, in some ways, is what every artist is searching for.”

Portrait by Sheree Hovsepian

This process of self-reflection has, for Johnson, largely been through various forms of abstraction – a build-up of spontaneous gesture, vibrant colour and embedded layers of symbolism – which, as Megan O’Grady points out in a recent article in The New York Times, aligns his practice with a new generation of black abstract painters such as Mark Bradford and Shinique Smith who are also making non-representational work in ‘defiance’ against traditionally narrow expectations of how their work should express black identity. “None of us want to be the representative of any kind of idea or concern,” Johnson continues, “and that’s not to suggest that I see the purpose of an artist as being an individual genius – I don’t subscribe to that concept at all – but I do see the artist as an individual living in the world and interpreting that world from a very specific location.”

Read more: How will the art industry change post-pandemic?

Inevitably, that location changes over time, and Johnson’s initial interest in the art world was that it might be “really exciting to be a filmmaker”. Arriving at Columbia College in Chicago, however, he found he had registered too late and all of the film classes were full. He ended up graduating with a BA in photography in 2000, and later, at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, he took up painting, sculpture, installation and film. His directorial debut, Native Son, released on HBO in 2019.

Photograph by Sheree Hovsepian

He has become known for his distinct visual language, which comprises specific, non-art materials that reflect his own experience as well as referencing history, literature and philosophy – subjects he was taught to deeply respect by his mother who was a poet and lecturer in African history. One of his most frequently recurring materials is shea butter, which he sometimes carves into dense, golden, bust-like forms that appear amongst leafy plants in his large-scale steel structures. “One day, I was putting it on whilst listening to the Tavis Smiley Show on the radio and I just thought to myself: this is it, the honest space,” he recalls. “It’s a material that I’m actually using in my life and on my body and it talks about Africanness, and displacement and healing and moisturising and utility.” Interestingly, the more recent additions to his ongoing Anxious Men series see the artist returning to more traditional materials (oil and linen) and consciously placing himself “within the discourse of art historical engagement”.

Photograph by Sheree Hovsepian

Ever since his Anxious Men made their first public appearance, coinciding with the initial rumblings of Donald Trump running for president, the wild, boxy characters, rendered in a scratchy, urgent style, have become the symbolic protagonists of the artist’s practice. But it is the Broken Men series (2020) that leave an even deeper impact. Monumental to the point of being intimidating in their scale, the works in this latest series comprise fractured mosaics of cartoon-like figures assembled from cracked ceramic and glass, scribbled over with paint, melted black soap and wax. Standing before them at Johnson’s solo exhibition ‘Waves’ at Hauser & Wirth in London at the end of 2020, I found myself struck by an allusion to the end of one era and the uncertain beginnings of the next. “We are now deconstructed, we will never be exactly the same,” Johnson agrees. “I’m not suggesting that the world wasn’t tragic and problematic prior to all of this, which of course it was, but this is my relationship to it now. We’re putting [the world] together again through a piecemeal process.”

With thanks to Maryam Eisler

For more information, visit: hauserwirth.com

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2021 issue alongside Rashid Johnson’s logo takeover.

Recent Comments