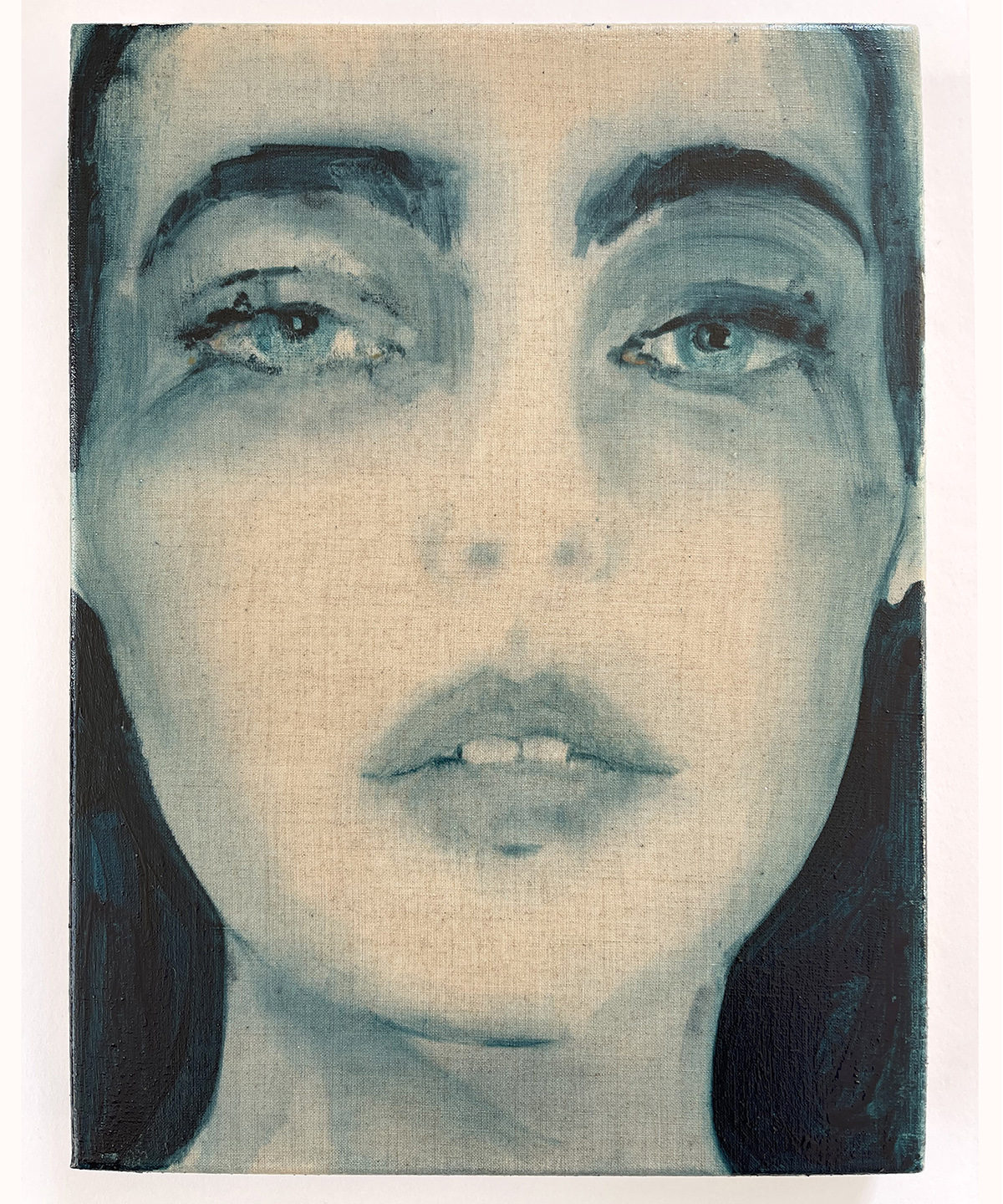

Lady Edwina Grosvenor. Photograph by Roo Kendall at Pencil Agency

Lady Edwina Grosvenor is the daughter of Britain’s richest landowner, the Duke of Westminster, and a passionate advocate for prison reform. She is the founder and chair of One Small Thing, an organisation that works with prisoners and staff in both male and female prisons, and a founding investor and ambassador of the Clink Restaurant chain, which trains prisoners for work in the catering industry. As part of our ongoing philanthropy series, she speaks to Samantha Welsh about her early work with prisons across the globe, the importance of training officers and her vision for the future

LUX: What are your earliest memories of wanting to give to make a difference?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: I was about 12 when my mother and father decided to take me and my older sister to a drug-rehabilitation centre on Hope Street in Liverpool to meet two heroin addicts, to understand about drugs and addiction. It was a pivotal moment. I remember realising there are reasons why people become addicts, and so my interest in human behaviour began. Years later, I realised I had money to give and there was a big internal wrestle with what that meant, what I was going to do with it, how I was going to do it, what would be the appropriate way. Then, at 15, I worked in a homeless shelter called Save the Family where mothers went with their children as a last-ditch attempt to prevent the children from being removed into care. The mothers were taught how to be parents. If you’ve never been parented yourself, how could you be expected to do it? I found that really hard-hitting as some fathers were either in prison, others had left, or they were dead. The mothers all had trauma-histories. I was the same age as some of the children that were there, they knew who I was and they challenged my family background. It made me think.

Working with Save the Family and visiting the two heroin addicts on Hope Street are the two really big moments in my life and both those happened before I was 16. From then on, I was always thinking, how is that fair, why have I got all this when others have so little?

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

LUX: When were you drawn to advocate for justice through prison reform?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: I travelled alone to Nepal when I was 18 to work as a prison’s assistant missionary in Central Jail, Kathmandu. I was going into prison to remove innocent children serving time alongside their parents. I remember the first four boys were all under the age of five. They’d never seen a white person, and they’d never been in a car. They were violently sick throughout the five hour trip from high in the remote Himalayas down to the flatlands of Nepal. It was just utter chaos, but wonderful chaos and I was doing something that other people don’t do.

LUX: So from the start, you knew you had go into prisons to be sure of making a difference?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: Yes. It only became obvious when I went into women’s prisons in the UK. The case studies were part of my graduate dissertation on children growing up in prisons. I found that government legislation and the prison system were not responding to the reality of what was happening in prisons. After graduating in Criminology and Sociology & Criminal Behaviour, I started working with women offenders and their children. I also started to understand how the law works by working in the House of Lords. So with this, my passion and resources, I could hopefully approach this problem from every angle and be effective.

Lady Edwina Grosvenor speaking at a conference

LUX: What characteristics are shared by the worst prisons you have visited?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: Overcrowding is a big problem, infections spread faster, it’s harder to manage prisoners effectively, it’s harder for staff to do their jobs well and its harder to run a good, clean, safe regime. Also, bad leadership. You can go to prisons that look grim but the leadership is outstanding, there’s great staff morale from the governor down to the officers on the wing and the prisoners have a sense of hope. As in business, there has to be good leadership top down through every pay grade.

LUX: How does understanding offenders’ past trauma help in reforming behaviour?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: I set up One Small Thing to understand trauma through a gender-lens. My organisation provides training for prison officers and at the end of the course, we emphasise one small thing: it’s about changing the question from ‘what’s wrong with you?’ to ‘what’s happened to you?’ The way men generally tend to deal with their violence is to externalise it whereas women often internalise it. For example, women are usually abused by the person to whom they say, “I love you” which is why they suffer more with mental health problems. If a prisoner tells you what happened to them, you stand a chance of understanding who they are, why they are behaving the way they are and then you can work with them more effectively.

Read more: New residences at hot selling Andermatt Swiss Alps

LUX: Is it possible to change the way that correctional institutions approach rehabilitation?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: It absolutely is – that is why I never get too downbeat about things because it is entirely possible. Negative culture can become very strong in some prisons and you can feel it. With One Small Thing, over six years we have been working across all the women’s prisons and the long-term high secure male estate, which is 17 prisons. We have been training the officers, putting interventions in for the prisoners and working with the leadership down through the ranks to bring about that cultural shift.

LUX: So changing the culture ‘inside’ increases the probability prisoners who have served their sentences do not reoffend once they are ‘outside’; the press has reported widely on the success of the Clink restaurants here. Can you tell us more?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: We have a five-step integrated approach at the Clink: recruitment to the programme, training, support, employment, mentoring. A lot of organisations can do one thing really well, but to be successful you have to do it all for someone not to reoffend. The mentoring is critical as it supports the hard work done whilst the person has been inside the prison training. Do you have a suit to go to your interview? Do you have a flat? Is it furnished? Do you have anyone to talk to? Maybe they can’t see their friends and family because they are part of their old life and they do not want to reoffend. It is painful.

LUX: How do you think academics and other professionals draw on your experience here?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: Our trauma work was adopted into policy and written into the Female Offender Strategy, published in July 2018 by the Secretary of State for Justice. The Clink restaurant chain has just announced its expansion in partnership with the MOJ across 70 more prisons.

LUX: Why have you had to contribute financial resources alongside your professional work?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: I think this is an interesting thing when it comes to the role of philanthropy, and the public sector. I decided not to set up a foundation so that I could give to things that weren’t registered charities. When you’re trying to bring about a system change, and do things that have never been done before, you have to do things entirely differently from the beginning. For example, the training that we put across the prisons came from California, and the author of the work is a lady called Dr Stephanie Covington. I was able to bring her from California over to England to start training the prison officers. We were then able to put her curriculum into the prisons, but none of that could have been done if I had a foundation because she’s not a registered charity; she’s a professional expert, consultant and author. The conversation I had with the head of the prison service was along the lines of “I’ve seen this amazing thing in California, we really need this across our women’s prisons.” He said, “Edwina, there’s no money.” So I said that I would pay for it and he said, “Edwina, there’s no one to organise it’. So I said that I would organise and he agreed. It worked so well that it has now gone into the male estate.

LUX: What upcoming projects are you looking forward to?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: I am working on a big five year pilot project called Hope Street. I am redesigning the justice system for women and their children in the community in the hope that we will prove concept and then it will be rolled out nationally across England and Wales. Hope Street is about offering a safe space for women to serve their sentences in the community alongside their children. There are fewer than 4,000 women in prison in this country in12 women’s prisons, many of whom are perversely sent there for their own safety. Most women are inside for non-violent crimes, the large majority are in for very short sentences. Their children get removed from them, this is about 17,000 children per year. Hope Street will sit across the county of Hampshire. The county boundary is relevant because you have the local police, the local probation, the local services and commissioning routes. We’ve designed Hope Street to fit into that local landscape. It’s designed to be replicable and scalable so that it could be rolled out nationally.

An imagined render of Hope Street. Photograph by EnAim

LUX: How does Hope Street work?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: Hope Street will reduce the number of women being sentenced to prison in Hampshire by being the safe and healing community alternative. Women and their children will be able to access holistic, wrap around support in one place. At Hope Street there will be flats for the women and children, intervention rooms, workshops and training facilities where the women will do the work the courts prescribe. It’s a real life, open community with a café for the public as well as the women themselves, a crèche, and a garden. When it’s time for individuals to move on to a less supported environment, Hope Street will provide move on accommodation and continued support through outreach workers. It’s been four years’ in the planning and development, construction has begun and we open in Q2 2022.

Read more: Tasting with sustainable Napa wine producer Beth Novak Milliken

LUX: What advice would you offer someone else with personal resources who wants to make an impactful difference?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: I think people who have a lot should be conscious of it, and think about what they might or might not like to do with it. Wealth can be an incredibly powerful and amazing thing but it can become toxic to manage. I’ve managed to think about my philanthropy firstly, as a career and secondly, as a hobby to be enjoyed. Even on holiday in Sri Lanka last year, I found a prison opposite our hotel and managed to get in. Dan, my husband said: “Have you noticed the prison’s there?” and I said, “Of course I’ve noticed the prison’s there!”

LUX: What is the most memorable moment of your philanthropic journey?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: A big impactful one for me was visiting twelve prisoners in the Secure Housing Unit (segregation) within Pelican Bay prison, a State Male Supermax prison in northern California. In this prison the officers had guns, riots were common place, alarm bells rang; it was a chaotic, violent place. I needed to see and understand the work that the men were doing to address the trauma that they had suffered and to see how it may fit back in our English system. These men were never going to see the light of day again, however, I heard them describe their compulsion for violence as a physical fire in the stomach that they could not stop “but what I can do now is recognise it, breathe through it, and I know I can control it now.” For the first time they were being given words to be able to articulate and therefore address and process some of the horrific things they had been through. The only two things the prisoners felt were wrong with the programme were that it should be expanded to the whole prison and the teaching should be in a classroom not a cage.

LUX: What are your next big challenges?

Lady Edwina Grosvenor: Getting Hope Street fully funded and open. We have £6 million left to raise of £26.2m in order to fully fund the five year Hope Street pilot. I would love to hear from people who would like to support us.

Find out more: onesmallthing.org.uk/hopestreet

Samantha Welsh is a contributing editor of LUX with a special focus on philanthropy.

Chef and culinary curator

Chef and culinary curator Editor-in-Chief, LUX Magazine and collectibles consultant

Editor-in-Chief, LUX Magazine and collectibles consultant Chef and culinary curator

Chef and culinary curator

Recent Comments