How do you lend form to light? With glass, as glassmakers and bespoke light fittings expert Lasvit demonstrates. Yuen Lin Koh investigates

The gentle vibrancy of the day’s first light, seen on the sparkle of a morning dew. The liveliness of sunrays scattered into a dance by the ripples of a stream. The calm of a shaft of luminosity, soundlessly pouring through the oculus of the Pantheon.

For what is essentially electromagnetic radiation — if we are to break it down by physical science — light possesses magic. It’s magic that can be seen, and certainly can be felt, yet has no form. Or does it have to be that way?

Translating to “Love and Light” in Czech, Czech Republic-based glassmaker the Lasvit Group lends physical form to light with every piece created. The medium is perfect in the dualities it presents. Crystalline clear, it is visible — yet invisible in its see-through quality. An amorphous substance, its atomic structure resembles that of supercooled liquid, yet displays all the mechanical properties of a solid — like fluidity frozen in time.

The company founded in 2007 might be young, but the craft is one that has been perfected through centuries. By combining the traditional artistry of North Bohemian glassmaking with the innovative creativity of world class designers, architects, engineers and lighting technology, Lasvit brings Bohemian glassmaking and designing to a new level. Well-known for its high profile collaborations with cutting-edge design leaders including the likes of Ross Lovegrove, Oki Sato of Nendo and Michael Young, and well-loved by consumers for their iconic collections such as ‘Bubbles in Space’, Lasvit is also revered for its bespoke services that have lit many private and public spaces around the world with their magic.

The shimmering lattice of 250,000 crystal pieces and 12,800 artistic hand-blown glass components, stretching like a web across a diameter of 16 metres on the ceilings of the Jumeirah hotel at Etihad Towers in Abu Dhabi. Giant textured bent glass structures connected to a cascade of hand-blown, hollow glass drops, lit by LED and optical fibre to become whimsical “jelly fish” that float atop the futuristic Dubai Metro Stations. The “Diamond Sea” of handblown glass — some dazzling clear, some in amber tones, some twisted, some curved — creating waves that shimmer above the patrons of The Ritz-Carlton, Hong Kong.

Majestic in proportions and intricate in detail, each is a shining example of excellence in craftsmanship. Yet each is also an artistic expression — not just of Lasvit’s designers, but also their patrons. Certainly, given carte blanche, their stable of 14 in-house designers can dream up the perfect piece for any space — be it the lobby of a hotel or the dining room of a private home; but more importantly, they have the ability to translate your desires into designs that articulate your message.

‘liquidkristal’ – Developed in collaboration with Ross Lovegrove, the panels explore the innovative use of the material.

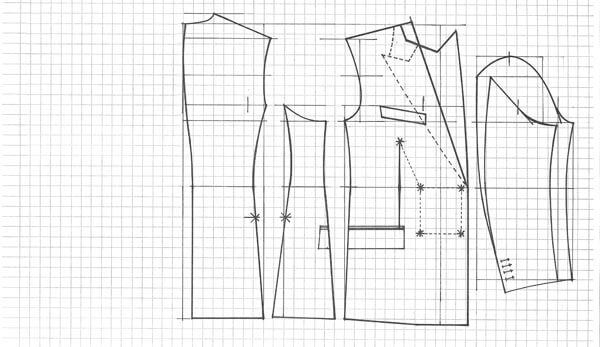

Fine-tuned through rounds of revisions with the client, the designs are then detailed through construction drawings and crafting. Each piece of handmade glass is created at the Lasvit facilities in Novy Bor at the Northern part of the Czech Republic — a pine-forested region steeped in glassmaking traditions since the 13th century. There, master glassblowers from families who have been making glass for generations, and who have honed their personal skills over decades, create what is known as Bohemian glass, known best for its inimitable sparkle.

The creation of every handmade piece remains a very basic process. The glass is made as how grandmothers cook: by feel, rather than by following recipes or formulas. In six ovens roaring at 1600°C almost 365 days of the year, glass is kept at a molten state, waiting to be blown, fused, flameworked, sandblasted, engraved or even hand-painted on — waiting to be transformed into wondrous forms.

The craftsmen labour in the glass studios, sipping on beer — it is the supplied drink preferred for its nutritional value and cooling abilities given that the studios burn at about 40°C all the time. They might look a little rough on the edges, and seem a little brusque in their mannerisms, but they work with glass with the tenderness of fathers cradling their newborn. The organic nature of the medium gives it a temperament that is not to be learnt from books, but to be understood from interaction — just as a child is to be known.

Yet this human element is apparent even in technical glass — machine-made pieces ranging from dainty crystal-cut glass beads to Liquidkristal from Lasvit’s Glass Architecture Division — transparent, undulating crystal walls that lend a mesmerisingly dynamic dimension to still structures. The human expression manifests itself in the creativity and artistry of applying these pieces, of transforming cold, hard components into works of art. “Glass is one of the most interesting materials that a designer can work with,” shares Táňa Dvořáková — a veteran designer who has been with Lasvit for six years, and also the creative mind behind masterpieces showcased at the likes of The Ritz Carlton DIFC Dubai, Shangri-La Tokyo, and now The Ritz-Carlton Residences, Singapore. Even for the seasoned designer, every piece holds a new surprise. “There is always a certain excitement — because when I finally illuminate the sculpture and see it installed, a new and more beautiful surprise is always revealed to me, often one I didn’t even expect,” she enthuses. For the piece at The Ritz-Carlton Residences, she took her inspiration from flowers, “particularly poppies and wild flowers: their freely growing petals have always fascinated me”. With childlike wonder, she expressed the delicateness of the subject in the form of a light sculpture composed of petals formed from a lattice of crystal-cut glass beads — “as if, unable to deal with the ephemeral beauty of this wild flower, someone had transformed it into an eternal diamond”.

The Ritz-Carlton Residences, Singapore, Cairnhill

A Lasvit piece hangs as the centrepiece in the dining area

Indeed the process is really as artistic as it is technical. The designers are often at the factories during the crafting of a piece, because it is one thing to follow technical specifications, and another to realise an artistic expression. Lasvit’s expertise is not just in the production of glass pieces — they also know exactly what it takes to mount an installation for safety and your peace of mind, and they even produce all the components, from metal structures to hanging materials. They also know just how to light a piece to bring it to life. Because when you love light as much as they do, you don’t just produce light — you capture the soul of it.

Recent Comments