In which our Editor-in-Chief travels from a neo-Mongolian skyscraping culinary landmark in Hong Kong to a 17th century tithe barn in Hampshire, and points between

Arriving in Hong Kong from London in the early evening, being whisked to my hotel and being checked in in-room, the call of mild has never been more powerful. A thorough room service menu, ranging from Cantonese to club sandwich, the assurance of brisk service and a half-bottle of 2009 Sauzet Puligny-Montrachet, a view from the sofa across to Kowloon, and a four-day schedule of meetings starting with no respect to jet-lag at eight the following morning: why would you venture out of your luxury hotel room?

Because… well, just because a friend who owns a tour operator had told me the Star Ferry to Kowloon is the best introductory experience to Hong Kong, and because otherwise the city would be viewed for the first time through the rose-tinted spectacles of dinners, lunches and parties with friends.

And so with pockets jangling with change for the ferry ticket machine, and the hotel doorman’s slightly perplexed ministrations that it would be much more convenient for me to take a taxi to Kowloon, uncomprehending of the fact that the journey was the destination, I headed through the tropical rain, along a latticework of walkways, past hurrying locals and the odd sauntering tourist, and took my place on a seat by the window. The churning journey across the few hundred metres to Kowloon plunges you into a valley of sea between mountain ranges of human endeavour and show, the edifices on either side; and then you are in Kowloon, and ducking into the lobby of an office skyscraper just before the downpour starts again.

Strange for a Westerner to travel to an acclaimed restaurant in the lift of an office building, but exit on the 28th floor and this is the world of Hutong, a sort of Inner Mongolian gastronomic temple (I later learned that it is designed to mimic Ancient Peking) complete with contemporary bar and ravishing guests. I sat at a table by the floor-to-ceiling window and gazed at the jumble of skyscrapers, each bigger than the last, spreading up and across and out, of Central, Hong Kong, obscured sometimes for seconds by drifting low clouds of the storm and then switched on again as the sky cleared. I toasted the view with a half-litre of draft Veltins, one of German’s finest, most aromatic lagers served icecold and surprising at Hutong. The cuisine is a meld of northern Chinese with whatever else they wish to serve, and my beef fillet with Sichuan chillis was edgy, precise and focussed.

The following evening I was taken by a friend to his new(-ish) restaurant, The Principal, in Wan Chai, a formerly sleazy, now rapidly yuppifying, area along the seafront that mixes massage parlours and ultra-cool shops in roughly equal measure. The Principal is unusual for Hong Kong, I was told, in that its entrance is on street level, which makes it very usual for where I come from. You walk through a gleaming bar area and into a restaurant room that is pared back, minimalist contemporary chic. The menu is Australian in its imagination, and quite contemporary London in its simplicity. The signature starter of baby beet, yoghurt, black quinoa and micro herbs was a quadratic equation of flavours with a very complete resolution; saltbush tenderloin of lamb with sweetbreads, aubergine, chickpeas and Moroccan ras-el-hanout was not North African so much as mid-Indian Ocean, and perplexing and delightful. My friend also owns a wine business, so the Wine Atlas, with picks of the most interesting wines from around the world, was very compelling. This sort of laid-back glamour is the new Hong Kong style, apparently, and London could rather do with some of its own.

Business finished at lunchtime on the last day in Hong Kong, a Sunday, so a friend who runs an auction house and I wandered down at teatime to the Captain’s Bar, a legendary institution in Central, the heart of town. In a part of the world where high floors and astronomical views are de rigueur for bars, it was arresting to be in a windowless space on a ground floor, an L-shape punctuated by glass tableaux of a chess game, low banquettes, and private jet set businesspeople of no fixed abode muttering deals to each other.

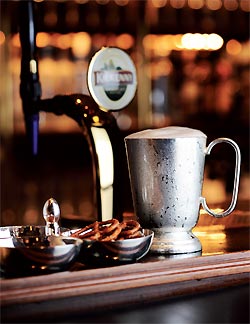

This is one of Asia’s most celebrated cocktail bars, but with a 12-hour flight ahead we weren’t in the mood for cocktails, instead finding solace in the metal tankards of extremely cold, perfectly headed Asahi lager. As the Germans and Belgians – and evidently the Hong Kongers – know, beer benefits from being served correctly as much as any wine appreciates its appropriate Riedel stemware. I had never had lager in a metal tankard before, but after two, we agreed that your own personalised, engraved tankard at the Captain’s Bar was an essential item for any gentleman of the world. My friend had auctioned off two of these for charity a year or two before, but sadly they are no longer available, so I left Hong Kong with a slight sense of yearning.

I have wanted to visit the Hotel Arts in Barcelona for more than a decade, but despite a number of trips to the city, never quite managed to make it. Back in 1998, the world, or Europe in any case, had seen nothing like it: a new build skyscraper devoted to showing off artworks to its guests, more six-star than five. In a city as earthy as Barcelona, it is a strange and rather liberating feeling to be hoisted 20 floors into the sky and survey the scene from above, Asian-style. My room was a paragon of contemporary comfort: silence, a perfectly-sprung bed, a bathroom with the glass walls that are essential parts of a hotel designer’s repertoire now (affording more physical space as well as a feeling of it). And if you tire of Barcelona’s rather impressive (for a big city) public beach on the doorstep, you can view what is probably Spain’s finest overall collection of contemporary art or retire to the hotel’s own pool, stretched out just below the landmark Frank Gehry fish sculpture, which could be said to have kickstarted the whole contemporary design trend in northern Spain. The pool’s architecture is such that it reminded me rather of the Villa d’Este’s pool on Lake Como, famously floating in the lake on its own pontoon, even though the Arts’ pool is very much on dry land.

Without wishing to belittle the hotel’s art offering, which is compelling and makes a stay rather like staying in a contemporary museum, my highlight was art of a different form, in the restaurant Arola. This is food with wit, taste and just enough conception: cod esqueixada with tomato pearls, very particular patatas bravas, sea cucumbers and razor clams with kalix (which reminded me of samphire) were wonderful and not overdone. The artistry of the form of the dishes was matched by their culinary execution; here is another example of modern Catalan cuisine taking its inspiration from Ferran Adrià’s now departed El Bulli but painting with its own palette, so to speak. And one of the most refreshing factors was its informality: Arola is conceived as a modern take on a tapas bar, so the service was swift and down-to-earth, not remote and Michelenic.

Home territory this summer featured a tour of the ancient hillsides of the Cotswolds, and a delve further south. I was struck a few years back when a friend who owns some of the coolest hotels in the world told me he considered Barnsley House as his favoured retreat in the now-ultra-fashionable hillsides and wooded folds between Oxford and Gloucester. England has recently been host to a number of spectacular country hotel openings, and I went expecting a grand super-Cotswold resort, only to be greeted by a bijou little property, all higgledy rooms and hidden staircases, tastefully refreshed in a contemporary style.

Our suite was in a former stable, approached along stepping stones in its own private garden – very St Tropez and perfect for a shy rock star making an escape with the wrong person’s girlfriend, in its seclusion. Inside the palette was light and contemporary, an offset to the building’s history. It was all very refreshing, although the garden and private water area could perhaps have been more organic, more easy on the eye. For those who want country without Country Life, Barnsley House is probably a perfect weekend stop.

As traditional and cosy as Barnsley House is New Gen Chic, Woodstock’s Feathers hasn’t changed much, barring the required investment in keeping everything up to date, since I used to escape there on Sunday evenings with friends while a student at Oxford in the late 1980s. This establishment fixture can accurately claim to be the Gateway to the Cotswolds; it is also on the doorstep of my favourite stately home in the area, Blenheim Palace.

The Feathers has been nurtured lovingly into the modern era, not jolted into it: fabrics and warm and autumnal, grandfather clocks still stand, history is alive, but there is a lack of fust and fuss. There is a feeling of cosiness, enhanced by the enclosed (in the best possible way) nature of its 17th century buildings. Service is friendly and country, not town, and you get the feeling that a gin and tonic, rather than a raspberry Martini, will be the favoured drink here for a century to come – although naturally they will serve you both.

Fifty kilometres is a distance that means nothing in China (unless you’re breaching the border between Hong Kong’s Special Administrative Region and China proper). In England, it takes you to a different part of the country, as a foray to Norton Park from the Cotswolds attested. Steep rolling hills are replaced by broad downs and open plains, and Norton Park makes the most of these views and its wonderful and vast 17th century tithe barn. Here is a new-style country hotel of a different perspective; the simple, well-sourced and thoughtfully cooked country cuisine tells the tale of a country whose culinary history has been jolted out of a shameful past in just the last 10 years.

Norton Park’s new building is removed by some ancient woodland from its original manor house, where we found snug ceilings, secret passages, and a lawn leading to a duckpond and an overgrown copse; ancient meeting modern.

Darius Sanai is Editor-in-Chief of Condé Nast Contract Publishing

Recent Comments